View this report

Introduction

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK has experienced year-on-year increases in deaths from alcohol. Between 2019 and 2021 there was a 27.4% increase in alcohol-specific deaths, reaching the highest number on record.[i] Policies to reduce the affordability of alcohol – such as increasing alcohol duty in real terms – are among the most effective and cost-effective ways to reduce harm.[ii] It is therefore a particularly bad time to allow alcohol duty to decrease in real terms.

Despite this, in the run up to every Budget and Autumn Statement, the alcohol industry vociferously lobbies for alcohol duty to be cut or frozen (a real terms cut). The industry argues that doing so brings in more Treasury revenue, and that uprating will damage production, lead to job losses, pubs being forced to close, and is unfair on consumers and economically disadvantaged people. Yet none of these arguments stand up to scrutiny.

It is important to remember that ‘uprating’ or ‘increasing’ refers to raising nominal duty rates by inflation, in order that duty revenue stays the same in real terms and doesn’t fall. So uprating is simply maintaining the status quo.

Although the default assumption of the Treasury and Office for Budget Responsibility is that alcohol duty will be uprated with inflation from 01 February each year – so that alcohol does not become cheaper in real terms – the impact of industry lobbying has meant that duty has been cut or frozen most years over the past decade.

Due to different government approaches to alcohol duty over the past 15 years, it is possible to compare periods of consistent uprating of duty with periods of (almost) consistent cuts and freezes. Labour’s Chancellor Alistair Darling introduced the ‘alcohol duty escalator’ in 2008, which automatically uprated duty every year by 2% above inflation. This ran until 2014 (although beer duty was cut in 2013 and 2014 and spirits duty in 2014), when it was abolished by Conservative Chancellor George Osborne. From 2015 until 2022, alcohol duty was cut or frozen every year, apart from in 2017. It is therefore possible to draw parallels between these two very different periods and approaches to alcohol duty.

Comparing the two, it is clear that uprating alcohol duty does not have the cataclysmic effect alcohol industry lobbyists argue it will. During both periods, alcohol production and sales remained very stable or grew, with major drinks companies recording massive profits (see Myths 1 and 2). Pubs have closed at a similar rate during both periods (Myth 3). Employment numbers in pubs and bars remained remarkably stable (Myth 4). And uprating is clearly not regressive when taking health effects into account, a crucial consideration for a public health lever (Myth 5).

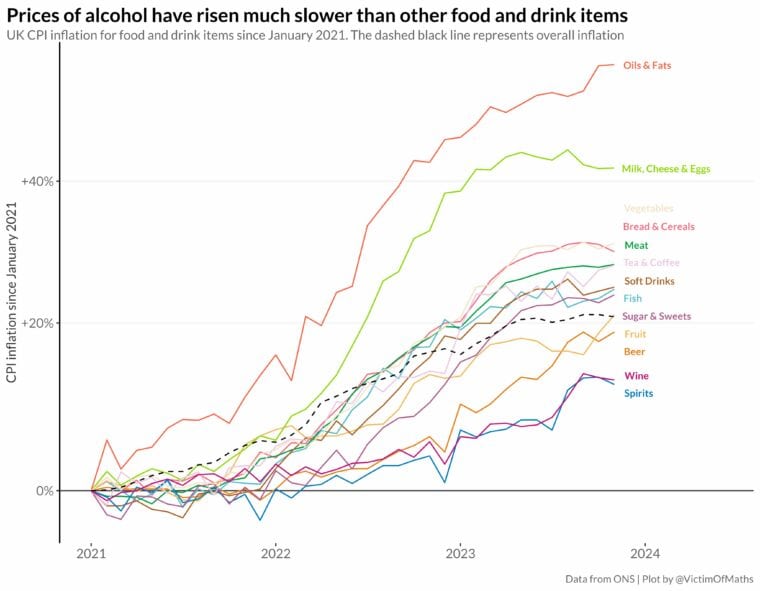

The overwhelming public health argument for reducing the affordability of alcohol should always be considered too. Freezing duty leads to alcohol becoming more affordable, which increases the number of deaths and hospitalisations. Decisions to cut and freeze duty between 2012 and 2019 led to an estimated 2,223 additional deaths in England and Scotland and 65,942 additional hospital admissions.[iii] This tax break to an already hugely wealthy alcohol industry is not only unnecessary – since the industry has done very well during periods of uprating – but also fuels a public health crisis during a time of record high deaths from alcohol. Analysing data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), health economist Colin Angus has shown that, as of December 2023, beer, wines, and spirits were the only major food and drink categories to have become cheaper in real terms since the start of 2021.[iv] As alcohol is a discretionary, non-essential product, that causes over 25,000 deaths in the UK each year, it is disheartening that – partly due to government policy – there has been such a stark contrast between how much more expensive essential goods have become compared to alcohol in the cost-of-living crisis. Particularly at a time when Treasury revenue could be used to finance public services and reduce economic inequality.

The media and politicians consistently overestimate the public appeal of freezing duty. Most people would prefer alcohol duty to be uprated rather than other taxes. A YouGov poll by The Times in 2023 found that the government’s decision to freeze alcohol duty was the least popular measure in the Autumn Statement.[v] Only 38% of people supported the decision to freeze duties, with 47% of the public saying it was the wrong priority for the country at the time.

A 2023 study by IAS found that there has been a wide variety of messaging used by governments in communicating decisions on alcohol duty between 2008-23, with sometimes conflicting objectives and no clear long-term strategy.[vi] Many of the industry myths outlined in this report have been articulated within government duty announcements over the years. By reflecting on the veracity of these statements, the government can be more consistent with their messaging, while supporting both the economy and public health.

In this report, we look at six of the most prevalent arguments made by the alcohol industry when it seeks to have duty cut or frozen, and we demonstrate why these are fallacious.

MYTH 1: “Cutting and freezing duty brings in more revenue to the Treasury.”

FACT: Cumulatively, duty cuts will cost the Treasury £24 billion from 2013-2028, compared with if duty had been raised in line with inflation as was planned.

Alcohol duty receipts have risen linearly over the last 20 years, with no outlier when the duty escalator was in place, from 2008-2014.

Reduced alcohol consumption would be offset by spending on other products and services, which, together with the public health gains, would be unambiguously good for the UK economy.

MYTH 2: “Uprating will damage alcohol production and sales.”

FACT: Alcohol production and sales remained remarkably stable – or grew – both when the duty escalator was in place and during subsequent cuts, even when adjusting for inflation.

MYTH 3: “Freezing duty supports pubs and hospitality. Uprating will lead to pubs closing.”

FACT: Freezing and cutting duty makes supermarket alcohol relatively more affordable so encourages people to drink at home more. And pubs have continued to close despite duty cuts and freezes.

Pub landlords see supermarkets as the biggest threat to their pubs, not duty.

Contrary to popular belief, the pub sector as a whole hasn’t been in chronic decline. As with many industries, the pub sector has evolved over time, with more successful pubs pushing out competitors and a trend towards fewer pubs, employing more people.

MYTH 4: “Uprating duty would lead to job losses in the hospitality sector.”

FACT: Uprating by the duty escalator mechanism didn’t change employment numbers and uprating duty would help slow the move to home drinking.

MYTH 5: “Uprating unfairly penalises moderate drinkers and disproportionately hurts disadvantaged people.”

FACT: Alcohol duty increases barely affect the finances of people drinking within the guidelines and evidence shows they reduce health inequality.

For someone drinking a bottle and a half of wine each week (within the low risk guidelines), a 5% uprating of duty would only cost them £10 more each year.

Economically disadvantaged groups drink less yet suffer more alcohol harm. These groups are also more price sensitive so would pay less of any uprating. There is strong evidence that alcohol price increases reduce health inequalities.

MYTH 6: “It’s unfair on spirits compared to beer and cider.”

FACT: Alcohol duty should be based on the strength of products, with stronger products paying more. This will help incentivise the production of low strength, less harmful drinks.

In addition, it’s generally much cheaper to produce spirits than beer, cider, or wine, so spirits should be taxed more.

Cider should not be preferentially treated though and should have the same rates as beer.

[i] Office for National Statistics, Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2021 (2022).

[ii] World Health Organization, SAFER Initiative (accessed January 2024).

[iii] Angus, C. and Henney, M. Modelling the impact of alcohol duty policies since 2012 in England and Scotland. The University of Sheffield and Institute of Alcohol Studies (2019).

[iv] Angus, Colin. Prices of alcohol have risen much slower than other food and drink items, Twitter/X (Dec 2023).

[v] Wright, Oliver. Autumn statement brings Tories four-point bump in polls, The Times (Nov 2023).

[vi] Boniface, Sadie. How have governments communicated UK alcohol duty policy changes?, Institute of Alcohol Studies (2023).

View this report