View this report

Summary

- Alcohol places a significant burden on the emergency services, not only on the servicepeople’s health and wellbeing, but on the services’ resources too

- An estimated three-quarters of those who come into contact with the UK’s criminal justice system have a problem with alcohol

Introduction

Survey data suggests that alcohol takes up most of emergency service frontline staff’s time, at huge cost to the UK taxpayer. Emergency service workers see a combination of increased public health treatment provision and stricter licensing regulation and enforcement – especially of off-licensed premises – as the solution to the problem.

Within the criminal justice system, the Prison Service and the National Probation Service have warned about the lack of well resourced and coordinated alcohol strategies to cope with the problem of alcohol misuse in UK prisons. In recent years, there have been attempts to provide community-based treatment for substance misuse on re-offending, which have had positive impacts on prisoners with alcohol dependency issues.

This briefing describes the monetary, social and health costs of alcohol on the emergency services, and the scale of the problem of alcohol on the criminal justice system too.

Alcohol and the emergency services

Alcohol places a significant burden on the emergency services, not only on the servicepeople’s health and wellbeing, but on the services’ resources too. An IAS survey of frontline staff confirms the magnitude of the problem: alcohol takes up as much as half of their time. The issue is particularly acute for the police, for whom 53% of their workload, on average, is alcohol-related [1] – more than four fifths of weekend arrests are alcohol-related [2].

The cost?

Research has shown that the criminal justice system spends £1.7 billion every year responding to alcohol-related crime [3], while the broader cost of alcohol-related crime to UK taxpayers is estimated by the Home Office to be £11bn per year, at 2010/11 prices [4].

The harm?

- Three quarters of police respondents, and half of ambulance respondents, had been injured in alcohol-related incidents [5]

- Between a third and a half of all servicepeople had suffered sexual harassment or abuse at the hands of intoxicated members of the public [6]

- 78% of police, 65% of ambulance staff, and 35% of Emergency Department Consultants feel at risk of drunken assaults [7]

What can be done

It was clear from survey respondents that there was a desire for policy action, although there was discussion over how best to reform current practices. Suggestions included [8]:

- Alcohol Treatment Centres

- Delivery of Identification and Brief Advice (IBA)

- A lower drink drive limit of 50mg of alcohol per 100ml of blood to bring England and Wales in line with Scotland, Northern Ireland and the rest of Europe

- Improving information sharing between emergency departments, police services and local authorities

- More assertive use of licensing powers by local authorities

- Reducing the affordability of alcohol.

There was support from the police for stronger control and regulation, particularly on licensing and alcohol prices. Many called for a return to earlier closing times for pubs, bars and nightclubs – the huge strain that later opening hours have created for police officers was apparent. They were also very supportive of levies on licensed premises (known as late night levies (LNLs)) to fund police activity – 89% were in favour [9] – and were keen that this should not be focused solely on pubs and bars, but that supermarkets and off-licences should be targeted as well.*

Alcohol and the criminal justice system: the scale of the problem

It has been estimated that around three quarters of those who come into contact with the UK’s criminal justice system (those in police custody, probation settings and the prison system) have a problem with alcohol, and over a third are dependent on alcohol [10]. A review of evidence of alcohol use disorders in the criminal justice system, ranging from 2000–2014, found that:

… between 64% and 88% of individuals in the police custody setting had an alcohol use disorder. In the magistrates’ court this was 95%; 53%–69% in the probation setting and between 13% and 86% in the prison system [11].

Prison

Many prisoners surveyed have indicated they had been drinking at the time of committing their offence – figures as high as 70% have been reported [12]. Data published by the Ministry of Justice in 2013 showed that 63% of prisoners who drank alcohol in the four weeks before custody would be classified as binge drinkers under NHS Choices measures [13]. The problem may be particularly acute for women, with surveys suggesting women are substantially more likely to report a problem with alcohol on their arrival at prison; 30% of women compared with 16% of men [14].

Public Health England (PHE) and the Department for Health & Social Care have estimated that in 2016/17 almost half (49%) of adults receiving treatment in prisons, young offender institutions, and immigration removal centres presented with problematic alcohol use (either alone or in combination with other substance use) [15]. The figure for young people was similar (48%) [16].

In 2014, 1,091 prisoners in England and Wales were found in the possession of alcohol. Initial data for 2015 (up to 31 October) shows that 1,045 prisoners were found in the possession of alcohol, although this increase may be somewhat due to improved recording practices [17]. Almost a quarter of male prisoners have been found to report that it is easy to get alcohol in prison (compared with 7% of female prisoners) [18].

Inspection surveys of 13,000 prisoners, 72 inspection reports and surveys of drug coordinators in 68 prisons, revealed that in 2008/09, 19% of prisoners reported having an alcohol problem when they entered the prison, rising to 30% for young adults and 29% for women [19].

Probation

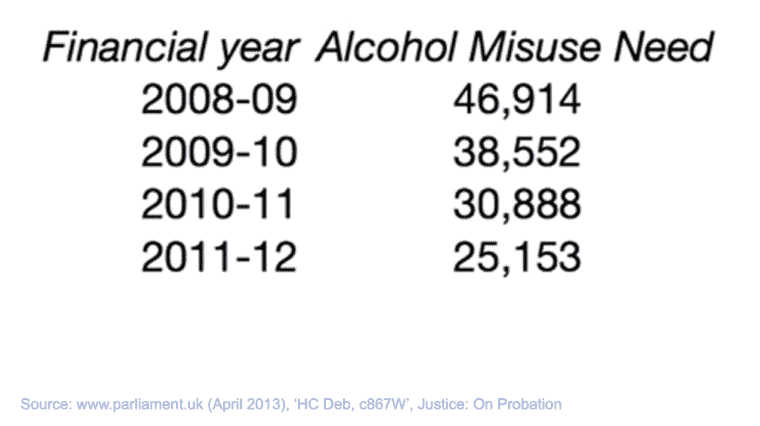

According to estimates from the National Offender Management Service (NOMS), based on completed Offender Assessment System (OASys) assessments, 25,153 offenders on supervision by the probation service had alcohol misuse issues in the 2011/12 financial year (see figure 1 below) [20].

Although this represents a significant drop in the annual number of offenders who have experienced problems with alcohol, it must be noted that a full OASys assessment is not required with all offenders, and therefore the actual number of offenders with alcohol misuse problems is almost certainly higher than the recorded figures suggest. Indeed, work performed which assessed the prevalence of alcohol use disorders in this population and compared this to official records from the OASys suggests that many of those who may need treatment may be overlooked. The authors noted that ‘around 40% of probation cases who were classified as either hazardous, harmful or possibly dependant drinkers on AUDIT were not identified by OASys’ [21].

Figure 1 Offenders on supervision by the probation service with alcohol misuse issues

What can be done

A thematic review published in 2010 by the HM Inspectorate of Prisons highlighted the failure of the Prison Service to address the problems of alcohol misuse in prisons adequately, despite repeated warnings by the Prison Reform Trust about its harmful effect on reoffending rates and the growing prevalence of alcohol-related crime. At every stage in prison, prisoners’ needs were less likely to be either assessed or met than those with illicit drug problems. Alcohol problems were not consistently or reliably identified and few prisons even had an alcohol strategy based on a current needs analysis [22].

A 2009 review conducted by the National Probation Service into alcohol-related interventions in prisons established that their effective commissioning and delivery had been hampered at a national level by a lack of:

- resources and dedicated funding for the provision of alcohol interventions and treatment

- guidance and protocols to inform the targeting of available interventions

- appropriate and accessible alcohol treatment provision

- probation staff confidence, skills and knowledge around alcohol-related issues

- success engaging and influencing local commissioners to afford greater priority and resources to work with alcohol-misusing offenders

The report concluded that the resulting shortage of British research evidence means there is currently limited scope for developing empirically informed guidance to instruct senior probation managers and practitioners on key issues [23].

The Coalition Government acknowledged the importance of prisons as places for rehabilitation and tackling dependency on alcohol. In its Alcohol Strategy, there were plans to develop an alcohol interventions pathway and outcome framework in four prisons, to inform the commissioning of a range of effective interventions in all types of prison. From April 2013, they also proposed to grant responsibility for commissioning health services and facilities for those in prisons and other places of prescribed detention to the NHS Commissioning Board (NHSCB) [24]. As of October 2013, a National Partnership Agreement was reached between NHS England, NOMS and PHE ‘for the co-commissioning and delivery of healthcare services in prisons in England’ [25].

The impact of community-based treatment for substance misuse on re-offending was examined by the Ministry of Justice and PHE in 2017. Following 132,909 clients across a two-year period, it was found that ‘alcohol only clients showed the largest reductions in both re-offenders and re-offending (59% and 49%, respectively)’ [26]. Further work from PHE exploring the use of alcohol brief interventions in prisons in the North of England with non-dependent drinkers ‘who commit a disproportionate share of crime’ [27], found that while the staff in these prisons were positive about the potential of the measures, there were many key considerations that need to be made; for example, the timing of the interventions, with release and post-release both suggested to be key times when intervention might be beneficial, and that messaging needed to be applicable to prisoner’s real life experiences and knowledge (and as such, unit information was seen as of limited effectiveness) [28].

* For more detail on these schemes, please see the Driving factors of alcohol-related crime paper

- The Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2015. Alcohol’s impact on emergency services, p. 3

- Stoddart, J. 2011. Alcohol’s impact on policing. Balance – The North East Alcohol Office, p. 19

- Leontaridi, R. 2003. Alcohol misuse: how much does it cost? London: United Kingdom Cabinet Office, p. 59

- www.parliament.uk. 2013. Written evidence from the Department of Health (GAS 01), in 3rd report – Government’s Alcohol Strategy, Health Committee

- The Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2015. Alcohol’s impact on emergency services, p. 4.

- Ibid. p. 4.

- Ibid. p. 4.

- Ibid. p. 7.

- Ibid. pp. 18–20.

- www.parliament.uk. 2016. Alcoholic Drinks: Misuse: Written question – 41699

- Newbury-Birch, D., McGovern, R., Birch, J., O’Neill, G., Kaner, H., Sondhi, A. and Lynch, K. 2016. A rapid systematic review of what we know about alcohol use disorders and brief interventions in the criminal justice system. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 12(1), p. 57

- Addaction. 2014. The Alcohol and Crime Commission Report, p. 9

- Hansard. November 2015. Prisoners: Alcoholism: Written question – 17328

- HM Chief Inspector of Prisons. 2016. Annual Report 2015–16. London: The Stationery Office. p. 55.

- Public Health England and Department for Health & Social Care. 2018. Secure setting statistics from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017, p. 6

- Ibid. p. 8.

- Hansard. 2015. Prisons: Alcoholic Drinks: Written question – 17683

- HM Chief Inspector of Prisons. 2017. Annual Report 2016–17. London: The Stationery Office, p. 113

- Ibid.

- www.parliament.uk. 2013. HC Deb, c867W, Justice: On Probation

- Newbury-Birch, D., Harrison, B., Brown, N. and Kaner, E., 2009. . Sloshed and sentenced: a prevalence study of alcohol use disorders among offenders in the North East of England. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 5(4), p. 201

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. 2010. Alcohol services in prisons: an unmet need

- McSweeney, T., et al. 2009. Evidence-based practice? The National Probation Service’s work with alcohol-misusing offenders. Institute for Criminal Policy Research, School of Law, King’s College, London, Ministry of Justice, pp. iii and iv

- HM Government. 2012. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy, p. 26

- National Offender Management Service. 2014. Healthcare for offenders

- Ministry of Justice and Public Health England. 2017. The impact of community-based drug and alcohol treatment on re-offending. p. 5

- Public Health England. 2017. Brief interventions in prison: Review of the Gateways initiative, p. 4

- Public Health England. 2017. Brief interventions in prison: Review of the Gateways initiative

View this report