Deaths from conditions wholly attributable to alcohol increase by one in 2023 compared to 2022 in Scotland, according to a report by National Records of Scotland.

1,277 deaths were recorded in 2023, one more death than in 2022 – a 15-year high.

Phillipa Haxton, Head of Vital Events Statistics, said:

The rate of alcohol-specific deaths peaked in 2006 and then fell until 2012. Since then it has generally risen.

Those aged 45-64 and 65-74 continue to have the highest mortality rates. If we look at the average age at death, that has risen over time. The mortality rates for those aged 65 to 74, and 75 and over, were at their highest since we began recording these figures in 1994. As the same time for age 25-44 the mortality rate has been fairly stable over the last decade.

Alcohol-specific deaths were 4.5 times as high in the most deprived areas of Scotland compared to the least deprived areas in 2023.

Scots aged 65 to 74 now have the highest mortality rate from alcohol of any age group – reversing patterns seen in previous decades when middle-aged drinkers were the most likely to die as a result of alcohol use.

Dr Peter Rice, chair of IAS and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP) told The Herald that the figures reflect a “cohort effect” from the “older part of the baby boomer generation moving through”.

It’s pretty striking to see that graph with the 65-74 year olds overtaking that of the 45-64 year olds. It fits with what SHAAP has been trying to do since we were formed in 2006 which was to draw attention to the chronic health harms in older age groups. When we started there was so much focus on ‘peak alcohol’ with ladettes and binge drinking.

Right from the start we had to emphasise that this is not just about – or even mainly about – young people and public disorder. This is about chronic health harms, and liver disease is our best indicator of that, and that comes mainly from home drinking. That’s the type of drinking we need to be particularly worried about in Scotland. Low cost alcohol in the supermarkets and people drinking that at home and running into chronic health problems. The last figures I heard were that 85% of alcohol sales are in off sales in Scotland. It was about 73% before the pandemic.

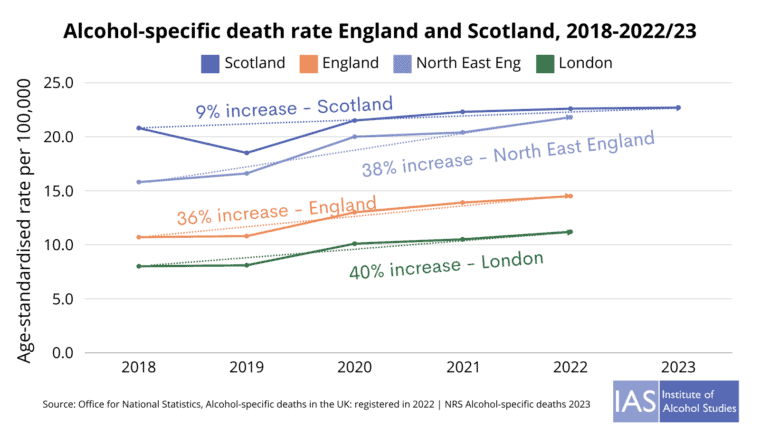

All countries in the UK have seen stark increases in alcohol deaths since the pandemic. The rate of increase has been lower in Scotland, likely due to alcohol policies such as minimum unit pricing (MUP) mitigating this rise. For instance, since 2018, when MUP was introduced, the increase in death rate in Scotland has been 9%, compared to 36% in England.

However, Dr Sandesh Gulhane, the health spokesman for the Scottish Tories, said the “disgracefully high” number of deaths showed minimum pricing had “monumentally failed”.

It has been a blunt instrument to tackle a complex problem, with those suffering from alcohol addiction skipping meals to buy more drink, even as SNP ministers hiked prices by 30 per cent during a cost-of-living crisis.

Jenni Minto, the SNP public health minister, said increasing the minimum alcohol price would have a positive impact on future statistics.

Research commended by internationally-renowned public health experts estimated that our world-leading Minimum Unit Pricing policy has saved hundreds of lives, likely averted hundreds of alcohol-attributable hospital admissions and contributed to tackling health inequalities.

The forthcoming price increase to 65p per unit which takes account of inflation, was selected as we seek to continue and increase the positive effects of the policy.