In this month’s alert

Labour’s first Budget keeps off-trade alcohol duty in line with inflation while increasing Draught Duty Relief for pubs – podcast feature

In the first Labour Budget for 14 years, alcohol duty rates were kept in line with RPI inflation. At the same time, Draught Relief was increased, to reduce the cost of most alcohol served on draught in the on-trade.

According to the Budget document, these measures will cost the Treasury an estimated £465 million between 2024 and 2030. The government assumes alcohol duty will keep pace with RPI each year, maintaining its value in real-terms. As a result, only changes that cut or increase rates in real-terms would impact revenue. The projected cost stems from the increase in Draught Relief.

The temporary ‘easement’ on most wine products will end on 31 January as planned.

Regarding Business Rates, the Chancellor announced there will be permanently lower business rates multipliers for retail, hospitality, and leisure properties from 2026-27.

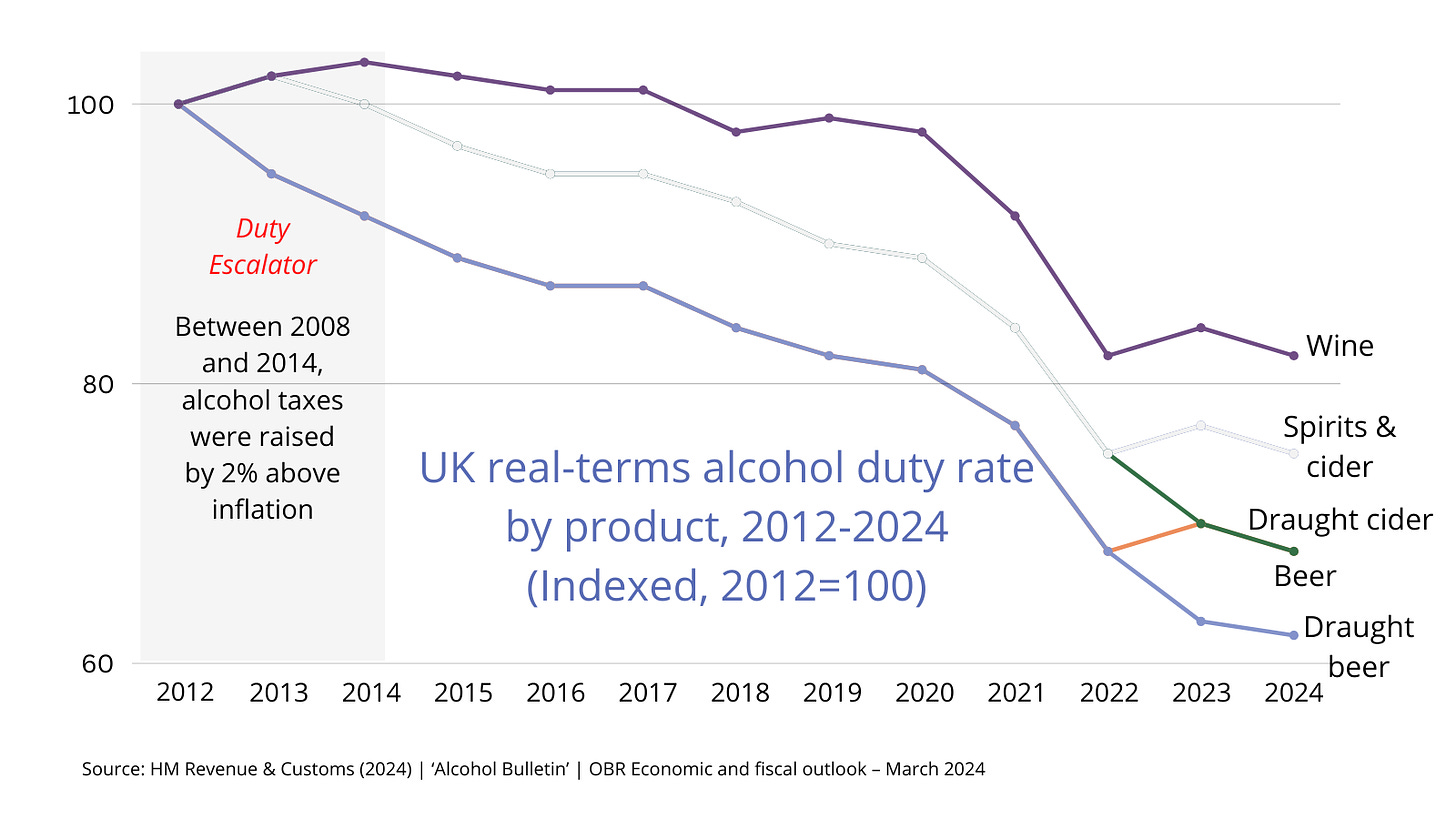

Over the past decade, alcohol duty rates have only been kept in line with inflation in 2017 and 2023. This has led to a significant reduction in the real-terms value of alcohol duty:

UK real-terms alcohol duty rate by product 2012-2024

IAS’s Chief Executive, Dr Katherine Severi, welcomed the decision but highlighted that rates were too low:

This will help narrow the widening gap in affordability between pub and supermarket alcohol. With nearly 80% of alcohol now consumed off-trade, we are no longer a nation of pub drinkers. This has contributed to the devastating rise in chronic harms from alcohol, including deaths from alcohol-related liver and heart disease.

There are both public health and economic reasons to move people back to drinking in pubs and not at home. In many areas, pubs are central to community life, promoting social cohesion in ways that solitary, home drinking cannot. People also tend to consume less alcohol in the on-trade, reducing overall alcohol consumption. And economically, hospitality requires far more employment than the off-trade, so could boost the economy.

Ultimately though, alcohol duty rates should cover the huge cost of harm that alcohol places on society, estimated at £27 billion in England alone. We would like to see the government consider an alcohol duty ‘escalator’, automatically raising duty above inflation at each fiscal event, as is in place with tobacco duty.”

Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, Chair of the Alcohol Health Alliance, also welcomed the move:

After years of government inaction and repeated freezes or cuts to alcohol duty, this increase is not only a necessary measure in light of rising alcohol-related deaths, but also signals a shift toward prioritising health over industry interests, protecting the most vulnerable, and mitigating preventable harm. We ask that the revenue raised from the duty increase be used to contribute towards frontline NHS and alcohol treatment services which are currently not equipped to treat the soaring numbers of people in need.

I commend the Chancellor for her leadership in putting public health at the heart of policymaking, and I am optimistic that this is the beginning of real change for alcohol harm reduction in the UK.”

Dr Peter Rice, Chair of IAS and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems, said it was good news for health and public finances, but that:

This increase merely maintains the real-terms value of alcohol duty, but the UK Government can go further. We would like to see the reinstatement of the duty escalator first introduced by former Labour Chancellor Alistair Darling which saw duty automatically uprated by 2% above inflation each year. When this was in operation, alcohol-related deaths began to fall and when it was scrapped by George Osborne, deaths started to increase again. Reintroducing this policy would ensure the public health and economic benefits of alcohol duty are maintained.”

Dr Aveek Bhattacharya, Research Director at the Social Market Foundation, was more critical, stating on X that:

The asymmetry of responses between those pushing for higher alcohol tax (“thank you so very much for this half loaf”) and those wanting it cut (righteous fury because for once the govt refused to let inflation erode duty) is so striking.

You would have thought it was the side that views this as a literal matter of life and death that would be spitting feathers, but not so.”

Listen to our podcast for more analysis from Dr Bhattacharya.

CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale, welcomed the Budget decisions, highlighting the support for pubs:

Despite general rises in alcohol duty next year, CAMRA is pleased to see the Chancellor’s decision to cut the rate of tax specifically on beer and cider served in pubs, clubs and taprooms. This will help pub goers as well as independent breweries and cider producers who sell more of their products into pubs, and recognises the principle that drinking in the community setting of the local pub is far preferable to the likes of cheap supermarket alcohol.”

Unsurprisingly, alcohol trade groups were less positive about the decision, since they vociferously lobbied for duty to be cut in real-terms. The Scotch Whisky Association claimed that Labour had broken its promise to “back Scotch producers to the hilt”. Chief Executive Mark Kent said:

It will damage the Scotch Whisky industry, the Scottish economy, and undermines Labour’s commitment to promote ‘Brand Scotland’. This further tax rise means the lessons have not been learned, and the Chancellor has chosen continuity with her predecessor, not change.

We urge all MPs who support Scotch Whisky to vote against this duty hike and tax discrimination of Scotland’s national drink.”

The Scottish Licensed Trade Association (SLTA) told The Telegraph that pubs and bars could end up closing thanks to a triple whammy of costs linked to the rises in the National Living Wage and employer National Insurance.

England to be the only UK nation without minimum unit pricing of alcohol

Northern Ireland is set to introduce minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol, after Health Minister Mike Nesbitt sought the backing of his executive colleagues to bring the legislation to the assembly.

On 17 October, he told Stormont’s Health Committee that he had asked officials to progress work on the introduction of the policy. At the meeting he said:

In particular, I would welcome your advice on where to fix any minimum price. It might be 50p, it might be 55p, it may be somewhere else.”

Figures indicate alcohol misuse costs Northern Ireland up to £900m a year, never mind the devastating impact on individuals, families and communities, and indeed the stress on the health service. In 2022, 356 people here died from alcohol-specific causes – that is the highest total on record.”

Nesbitt also said that the legislation would complement the Tobacco and Vapes Bill currently going through Westminster.

The news followed an event organised by the Institute of Public Health in Stormont in late September, where Nesbitt welcomed the opportunity to set out the “evidence and encouraging a public and political conversation on this important topic”.

Dr Roger McCorry, hepatologist and alcohol lead at the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, said at the event:

The compelling data generated from the Scottish experience of MUP demonstrates not only the potential for improved health outcomes for our population, but also the positive impact on stretched healthcare resources.”

In Scotland

Over in Scotland, on 30 September the minimum unit price was raised to 65p. This now means a typical 12.5% bottle of wine cannot be sold for less than £6.09 (up from £4.69) and a 500ml can of 4% lager will be at least £1.30 (up from £1).

The decision was made after research found that the original price had been eroded by inflation, leading to increased alcohol consumption and harm. The Sheffield Addictions Research Group found that the 50p price introduced in 2018 was now equivalent to 41p in real-terms. They also found that alcohol consumption was 2.2% higher than it would have been if the MUP had risen in line with inflation since it was introduced.

Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP) and Alcohol Focus Scotland (AFS) said the minimum unit price should be increased annually with inflation, to prevent “cheaper alcohol that causes the most harm” becoming more affordable over time. They also called for more measures to tackle the public health emergency of alcohol harms, such as an alcohol harm prevention levy on alcohol retailers, which could raise as much as £57 million a year to invest in alcohol treatment services.

Responding to the increase, Dr Tara Shivaji, Consultant at Public Health Scotland, said:

We’re pleased to see the Scottish Government introduce this increase. Scotland has the highest levels of alcohol harm in the UK but, since the introduction of MUP, we have seen that gap narrow.”

England next?

There have been murmurings of introducing the policy in England, with a Whitehall source telling The Times that: “Minimum unit pricing is also back and is seen as more likely to happen”.

An article in The Observer in early October said that:

Ministers are facing pressure to introduce minimum unit pricing for alcohol after Lord Darzi’s investigation into the NHS highlighted the “alarming” death toll in England caused by cheap drink.”

When approached by the paper, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care said:

For too long there has been an unwillingness to lead on issues like smoking, alcohol harm and obesity. Under our health mission we are placing prevention front and centre. This means prioritising public health measures…including reducing alcohol-related harms.”

Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, Chair of the Alcohol Health Alliance, said that minimum unit pricing was not a “magic bullet” but, given the number of deaths, it was “imperative” to act on prices, adding: “A duty escalator and minimum unit pricing would be an effective way of doing it.”

The most recent data available on the estimated impact of a 50p MUP in England indicate it would lead to:

Industry-funded mobile apps mislead users

A new study looked at the accuracy of information on 15 digital tools and apps created by alcohol-industry backed organisations in the UK, Ireland, USA, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, and found that many contain “blatant misinformation” and could push people to drink more.

The study – which was undertaken by public health doctors at The Royal Free London NHS Trust alongside the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine – also identified “dark patterns”, which are features that aim to manipulate and influence consumers for their own interests, nudging people to drinking more.

The authors said that there was clear evidence of “health misinformation and user experience features” in industry-funded tools that were:

Favourable to commercial interests and could negatively affect the accuracy or perception of health risk information.”

The apps included Drinkaware’s MyDrinkaware app, Diageo’s DrinkiQ app, and tools provided or funded by Educ’alcool in Canada and DrinkWise in Australia. The information was compared to the NHS Drink Free Days and Alcohol Change UK’s Try Dry apps.

Lead author Dr Elliott Roy-Highley said:

We found evidence of cultural targeting and peer pressure messaging, all the way up to obfuscating the proven risks of excessive alcohol consumption with blatant misinformation.”

All but one industry-backed platform omitted some information regarding the risks of alcohol consumption. Only 20% of alcohol industry-funded tools provided information on the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared to 70% of tools not funded by the alcohol industry.

Some tools, such as the Drinkaware unit calculator, misled users by suggesting only drinking above “binge levels” was harmful, researchers said.

A Diageo spokesperson said:

This report has taken individual findings and generalised them across the industry, which is unhelpful and completely inaccurate when it comes to DrinkiQ.”

Matt Lambert, chief executive of the Portman Group, said:

This is a deliberate and counter-productive attempt to discredit well-meaning resources and tools which are funded by the industry to prevent harmful drinking. It would be far harder to address harmful consumption without the active cooperation of a responsible alcohol industry, and let’s not forget that industry-funded initiatives have contributed to significant declines in harms such as underage drinking, binge drinking and drink driving over the last decade and more.”

Child drinking rates continue to decline, but still one of highest in the world

NHS Digital published its latest report on ‘Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use among Young People in England, 2023’. The report surveyed children aged 11 to 15.

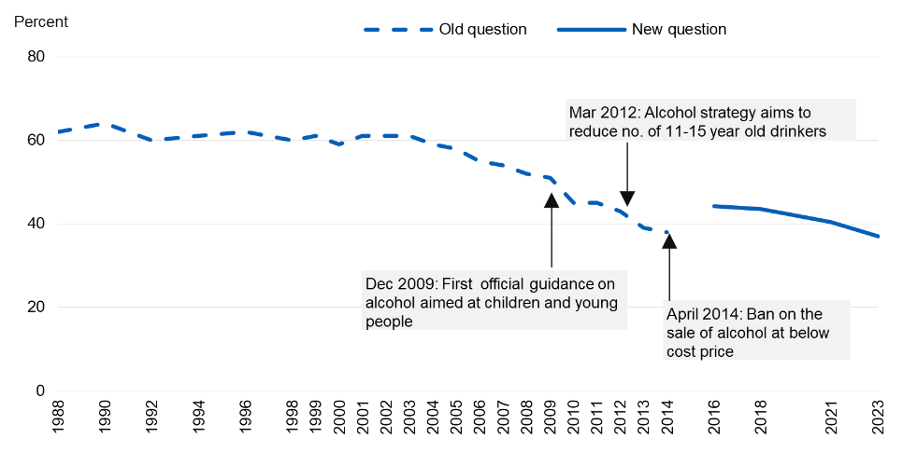

In 2023, 37% of pupils aged 11-15 said they had ever had an alcoholic drink, compared to 40% in 2021. This prevalence has fallen from 44% in 2016. Although the question changed in 2016 (so data cannot be accurately compared to before) the general trend clearly shows a decline in drinking from the early 2000s.

Ever had an alcoholic drink, by year

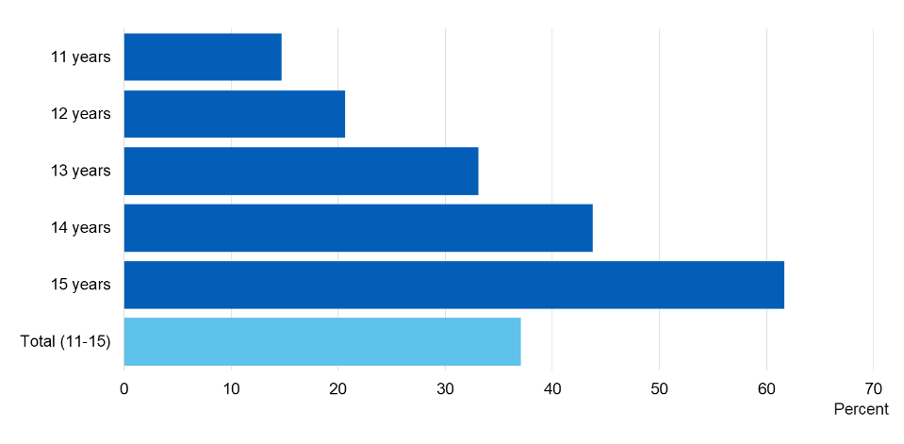

The rate of having drank before changes significantly across each age, with 15% of 11 year olds and 62% of 15 year olds ever having had a drink.

Ever had an alcoholic drink, by age

Regarding the prevalence of drinking in the last week – which classifies people as a ‘current drinker’ – 16% of 15 year olds had done so. Of these, almost a third (31%) drank 15 or more units. Boys were most likely to have drunk beer/lager (75%) and girls were most likely to have drunk spirits (75%).

Factors associated with pupils drinking are, in order of highest association: uses e-cigarettes; higher age; being White; takes drugs; family affluence; and smokes.

Despite these positive trends, England and the wider UK have some of the highest rates of children drinking across the world. Dr Katherine Severi spoke to The Guardian earlier in the year, stating that:

People tend to have this perception that introducing children to moderate drinking is a good way of teaching them safer drinking habits. This is untrue. The earlier a child drinks, the more likely they are to develop problems with alcohol in later life. Countries like France and Spain – where we assume children are introduced early – actually have lower rates of children drinking than England.

Evidence shows that parental drinking practices and how parents talk about alcohol are reflected in children’s attitudes towards alcohol and drinking. A pro-alcohol environment leads to the normalisation of drinking and ‘cultural blindness’ to alcohol harm among children. That’s true even with moderate parental drinking.”

Do alcohol ‘sobriety tags’ reduce reoffending?

Alcohol monitoring tags – or ‘transdermal alcohol monitoring devices’ – were rolled out in 2020 and have been used for people leaving prison who are ‘known to reoffend after drinking’ and therefore subject to an alcohol abstinence order. The idea is that while wearing the tag, the wearer cannot drink alcohol otherwise it will be detected in their sweat, parole authorities would then be alerted, and the individual could be called to court to face the prospect of further sanctions. Ultimately, the aim is to reduce alcohol-related violence and crime.

Up until now, when discussing the efficacy of the tags, the government has highlighted the high compliance rate, stating that 97% of wearers remained alcohol free. As Dr Carly Lightowlers, Senior Lecturer in Criminology at University of Liverpool, has previously pointed out, this ignores whether or not the tags successfully reduce reoffending after the tags have been removed.

A new study by Dr Lightowlers looked into this, as well as whether requiring offenders to undergo alcohol treatment reduced reoffending. She found that compliance was a fair bit lower than what previous research has found, at 78%. Treatment requirement completion stood at 68%. However, she did find evidence that tags reduced the likelihood of reoffending – wearers were 24-33% less likely to reoffend. There was no evidence that treatment requirements reduced reoffending. Read her blog on the findings here.

Dr Lightowlers does still urge caution about tagging, highlighting the limitations of her study, but also that there is a lot that could be done to reduce harm and crime associated with alcohol consumption that doesn’t involve criminal justice interventions.

In a 2022 blog for IAS, she highlighted that the tags extend the criminal justice approach to alcohol use, targeting individuals’ drinking through punitive measures rather than tackling the underlying health and social issues related to alcohol problems.

Urgent action needed in the Budget to improve the nation’s health

The Association of Directors of Public Health shared a joint letter with the Prime Minister and Chancellor, highlighting that urgent action is needed to improve the nation’s health, following austerity, the COVID-19 pandemic, and poor economic performance.

The letter, which was signed by over 60 organisations and experts, welcomed the new government’s positive start to improve the nation’s health, particularly regarding forming the Child Poverty Taskforce and commitments to tackle tobacco and junk food harm.

The ADPH calls for the development of a cross-government approach to public health:

With every department playing its part in achieving a healthier society, and using the levers of tax, regulation, and policy to tackle the biggest public health challenges – including climate change, child poverty, and health inequalities.”

Although they recognise that public sector funding is limited, the Association states that a £1.4 billion increase is needed to restore the Public Health Grant in England to the real-term equivalent of 2015/16 levels.

Mandatory regulation needed to crack down on junk food industry

In other public health news, The House of Lords Food, Diet and Obesity Committee published a report on 24 October that demands that the government develop a comprehensive, integrated, long-term new strategy to fix our food system, underpinned by a new legislative framework.

The report highlights the need for comprehensive, mandatory regulation of industry because the voluntary approach had failed due to the food industry not being incentivised to take action.

It also calls for the government to:

Exclude businesses that derive more than a defined share of sales from less healthy products from any discussions on the formation of policy on food, diet and obesity prevention.”

This call aligns with IAS’s recent good governance policy on managing conflicts of interest with the alcohol industry.

By the end of 2025, the Committee calls on government to:

Devise and publish a code of conduct on ministerial and officials’ meetings (whether in-person or virtually) with food businesses, to be employed consistently across all government departments.”

It also calls for the government to ban the advertising of less healthy food across all media by the end of this Parliament.

In related news, junk food adverts will be banned on bus and train services in Greater Manchester, Liverpool, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, and the West Midlands.

Kim McGuinness, mayor of the North East, said: “enough was enough” and “targeting” children with such adverts was “predatory”.

Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham, said that young people deserved “the best possible start in life” and the initiative had “taken the fight to the junk food giants.”

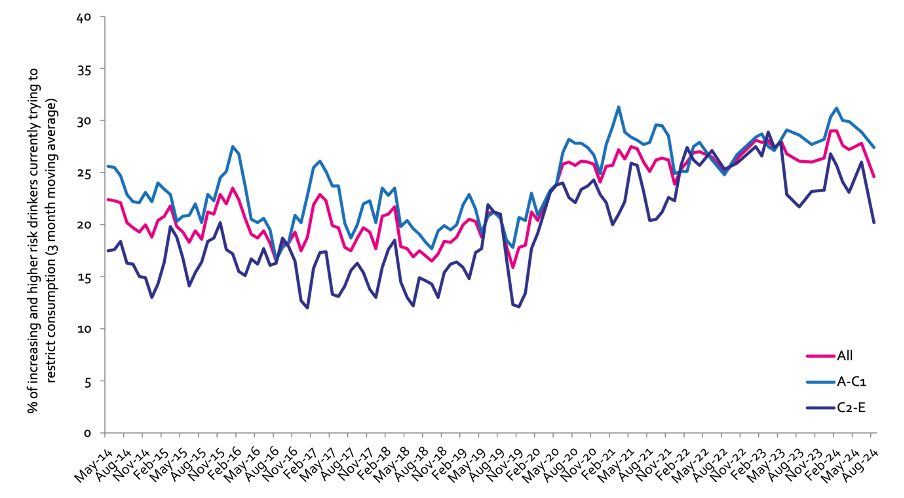

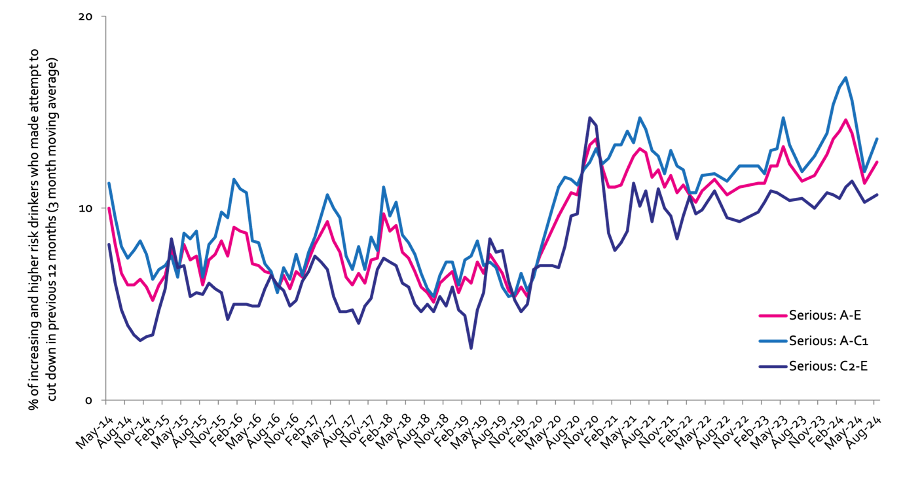

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

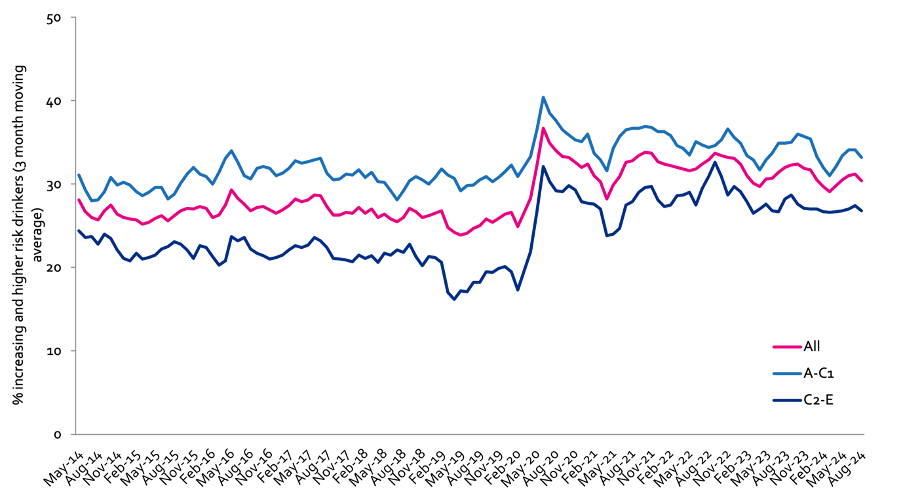

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

Serious past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question 1: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making. Q2: During your most recent attempt to restrict your alcohol consumption, was it a serious attempt to cut down on your drinking permanently? A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Government licensing reform sparks concerns over public health and local accountability

Professor Niamh Fitzgerald –

University of Stirling

Dr James Nicholls –

University of Stirling