In this month’s alert

A decade of failure – Self-regulation of alcohol advertising in Australia

1993 one of Australia’s foremost public health researchers concluded that unless the alcohol industry could demonstrate control over alcohol advertising the public could rightly demand that it be regulated by government (Hawks, 1993). A decade on, the latest system of self-regulation, administered from 1998 until 2003 by the alcohol industry, was found by government to have failed to operate effectively, despite the industry’s constant reassurance that the system could not be bettered.

Alcohol advertising in Australia is subject to two codes of practice. One is the Advertiser Code of Ethics which applies to all advertising and addresses matters of ‘taste and decency,’ primarily language, discrimination and vilification, violence, and sex. More specifically, alcohol advertising is subject to the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code (ABAC) which is controlled and administered by the drinks industry.

In summary, ABAC requires alcohol advertisers to “present a mature, balanced and responsible approach to drinking”. Accordingly, advertising “must not have strong or evident appeal to children or adolescents,” nor depict “the consumption or presence of alcohol as contributing to personal, business, social, sporting, sexual or other success”; nor suggest alcohol contributes to a change in mood or environment (ABAC, undated).

Four industry associations operate ABAC in the interest of “voluntary self-regulation”: the Australian Associated Brewers (AAB), the Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia (DSICA), the Liquor Merchants’ Association of Australia and the Winemakers’ Federation of Australia. Two key components of ABAC are the Pre-vetting panel, which previews advertisements in the developmental stage to ensure “they abide by the letter, and the spirit, of the Code”, and the Complaints Panel that adjudicates on objections to advertisements (DSICA 2002).

In the period under review the Advertising Standards Board (ASB) acted as the gatekeeper on advertising complaints: if they concerned the “taste and decency” code the ASB would adjudicate the complaint; if they concerned alcohol advertisements it would refer the complaint to the ABAC complaints panel.

The ABAC system functioned unimpeded for five years (NCRAA, 2003). Throughout the period the liquor industry insisted ABAC was working perfectly and no improvement was possible: “…Australia has a comprehensive self regulatory system in place that specifically prevents advertising directed at young people” (DSICA, 2002). It was also a global benchmark: “the industry’s voluntary code and its complaints system was one of the world’s most stringent” (Milburn, 2002) and the AAB said: “Australian brewers lead the world in strong self regulation of advertising” (Hudson, 2003). Individual companies proclaimed their commitment to the code: Carlton & United Breweries was “on the front foot [in terms of endorsing responsible drinking]” (Ligerakis, 2003) and Diageo asserted that code breaches were made by ‘small operators’ that were not representative of the industry (Howarth, 2004).

Despite these glowing self-assessments the ABAC was tightened in 2003 on the recommendation of the Ministerial Council for Drug Strategy, following a formal review that demonstrated the system had failed (NCRAA, 2005). The four posters are examples of advertisements which contributed to that conclusion.

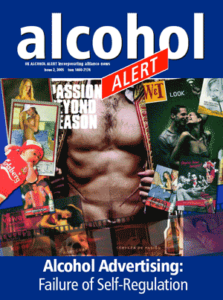

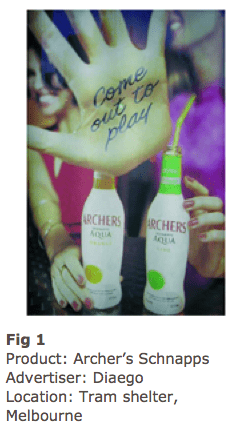

Diageo’s campaign for Archer’s Schnapps featured a slogan that employed archetypal children’s language, ‘Come out to play’, and used other techniques that seemed designed to attract the attention of minors. One version had the slogan written on the palm of a hand (fig 1) and another iteration had it forming a text message on a mobile phone (fig 2). As children are likely to write messages on their hands, and adolescents are adept at ‘texting’, the images were likely to resonate or young people. Their placement on public transport shelters, where minors congregate, offered intensive and extensive exposure to people who are too young to purchase the product. At a landmark Alcohol Summit convened by the New South Wales government in August 2003, the ‘SMS’ version was highlighted as exemplifying the licence taken by the industry (Gotting, 2003).

An advertisement for Beck’s Beer (fig 3) featured a scantily dressed woman lifting her top to reveal her bikini-style underwear. As with the previous advertisement, this was posted on public transport shelters in capital cities. It appeared to infringe the section of the code that prohibits an association between alcohol and sexual success. It could even be interpreted as depicting a female drinker offering sex. The Prevetting panel thought the advertisement consistent with the code because ABAC does not prohibit sexual imagery, and: “…this ad is a line drawing only, and does not depict a real woman.” The panel also thought it did not show or imply sexual success because only one person was present (Rubensohn, 2003). The ASB considered “…the majority of people would not be offended.” Despite those judgments this image was the subject of much attention in the official review of ABAC (NCRAA, 2003).

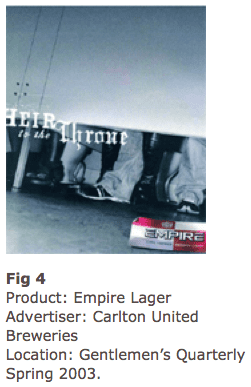

Carlton United Breweries responded to this climate by portraying a couple engaged in a sexual act in a lavatory cubicle (fig 4). This advertisement has added significance because CUB said it delayed the Empire Lager campaign until it heard the verdict on advertising at the Alcohol Summit (Ligerakis, 2003). Advertising came under sustained attack at the summit and national and state politicians threatened tighter regulation unless it improved (Ryan, 2003). On the basis of having released this advertisement after the summit it is impossible to think CUB treated the issue, the summit, or the code seriously. When challenged CUB asserted that the couple was not having sex but was acting “frivolously” (O’Neill, 2004). It is a significant admission, first because CUB could not afford to accurately describe the action, and second, it conceded that the image violated the injunction that advertising must portray “mature and responsible behaviour.”

By mid-2002 the discrepancy between the claims made by the alcohol industry for the integrity of its advertising and the numerous violations of the code was too obvious to be ignored. The Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy (MCDS), which is responsible for Australia’s drug strategy, instigated a formal review by an ad hoc body, the National Committee for the Review of Alcohol Advertising (NCRAA).

That decision amounted to a vote of no confidence in the stewardship of advertising by the liquor industry that maintained its system of self-regulation was “world’s best practice.” It is evidence that the industry was out of touch with community standards and had lost the confidence of public health officials and some key politicians.

NCRAA’s report confirmed the system was seriously deficient and had failed to ensure alcohol advertising complied with the ABAC. It found the public was largely unaware of the code and how to register a complaint; the process for judging complaints was too slow; decision-making processes were unclear, outcomes were not well reported, and the code did not include Internet advertising (NCRAA, 2003). It also discovered that the Complaints Panel had considered only 5% of complaints registered since 1998. Unless a complainant had referred explicitly to the ABAC code the ASB had adjudicated the complaint itself, according to the generalist advertising code, without referring it to ABAC (NCRAA, 2003). This meant the ABAC complaints process had not functioned, although the industry thought the system was working at the optimal level.

When complaints were adjudicated, they were dismissed. The ASB rejected every one of the 361 complaints it considered, and of the 20 investigated by the ABAC Complaints Panel just five were upheld (NCRAA, 2003).

As a result of the NCRAA report, MCDS made numerous recommendations regarding ABAC. The industry must report annually to MCDS on all complaints. Each complaint must be referred to the ABAC Complaints Panel and should be resolved within thirty days. A government official was added to the ABAC management committee and a public health expert joined the Complaints Panel; the code was extended to include Internet advertising and a protocol was to be developed for sponsorship of youth events. MCDS gave the industry six months to implement the changes and the amended ABAC system began on 1 April 2004 (NCRAA, 2005).

It is ten years since David Hawks suggested time was running out for the drinks industry in Australia to prove itself capable of self-regulation. An experiment of a further decade’s duration should be conclusive. During the ‘first’ ABAC regime industry bodies proclaimed the system was ideal, refused to countenance any improvement and maintained its implementation was faultless. But an inquiry found the system was ineffectual, and some components inoperative, with the result that advertisers flouted the rules and complaints were routinely rejected. The ABAC case showed the self-regulators were, at best, unable to distinguish between a viable system and one in extremis. That the industry retained the privilege of self-regulation is a measure of its political power and government’s reluctance to intervene in an era of deregulation. The minor changes to the code forced by MCDS in 2003 give some hope that the industry can be held to account due to continuing scrutiny.

REFERENCES

ABAC, The ABAC Scheme (undated)

Gotting, P. (2003) Summit leaves adland breathing easy, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September.

Hawks, D. (1993) Taking the alcohol industry seriously’, Drug & Alcohol Review, 12, 131-132.

Howarth, B. (2004) Advertisers test the limits”, Business Review Weekly (Magazine) 5 February, p62.

Hudson, S. (2003) ‘Brewers’ Of Substance 1, 1, p.6. Distilled Spirits Industry Council of

Australia (2002) “Alcohol advertising under attack, les/sep02.html

Ligerakis, M. (2003) Cold shot fired across Carlton & United’s bow, B&T Weekly, September 5, p7.

Milburn C (2002) Fines for reckless drink ads, The Age, 4 September, p.8.

National Committee for the Review of Alcohol Advertising. (2003) Review of the Self-Regulatory System for Alcohol Advertising, State Government of Victoria, Department of Human Services, Melbourne.

National Committee for the Reviewof Alcohol Advertising. (2005) Discussion Paper 2005, State Government of Victoria, Department of Human Services, Melbourne.

O’Neill P. (2004). Sex ‘used to sell alcohol to young’, Herald-Sun, 13 February, p.15.

Rubensohn, V. (2003) Personal communication, 16 August 2003

Ryan, R (2003) Industry bulldozed on booze ads, B&T Weekly, August 29, p.1.

Licensing – still on course for November

The Government insists that it is still on course for the new Licensing regime to come into force on 24 November 2005. Some licensing authorities and sections of the alcohol industry had urged a delay in view of the slow pace of applications to convert existing licences, which they argued made it impossible for the November start date to be feasible. Licensees had until 6 August to convert their old licence: after that date it became necessary for applicants to apply for a completely new licence under the new regime, with local residents having the opportunity to make objections.

According to the Government, around two thirds of licences had been converted by the beginning of August. It appears that the major pub companies and super market chains got their applications in by the August deadline, with the third of premises that failed to do so being disproportionately comprised of smaller, independent outlets such as ethnic minority restaurants. It is suggested that licensees whose first language is not English may have had particular difficulty in understanding the lengthy and complex forms that now have to be completed by applicants.

It seems that, as expected and as desired by the Government, applicants are taking advantage of the new regime to extend their hours of trading, with many being given licences to trade up to 2am or beyond. The major supermarket chains appear to have adopted a general policy of seeking 24 hour licences.

Controversy Rages On

The argument about the feasibility of the timetable for implementing the new legislation was minor compared with the continuing controversy over its likely impact on crime and disorder, health, and the quality of life of local residents and visitors to town centres.

The Government, the British Beer and Pub Association and allied commercial interests clung resolutely to the agreed line that everyone will be a winner from the new Licensing Act which, they insist, will improve life for everyone, bringing peace and calm to the streets with civilising drinking habits without, of course, encouraging people to drink any more than they do now. Virtually everyone else remains fearful that the quality of life of more or less everyone except binge drinkers and the businesses that sell the alcohol to them will deteriorate. During the summer, vocal opposition to the Government’s plans was heard from Parliament, the police, the judges, local residents, and an academic, Professor Dick Hobbs, who accused it of actively promoting a “binge economy”.

According to The Times newspaper, up to two thirds of all licensed premises and 90% of bars, around 130,000 premises in all are taking advantage of the new laws to extend their hours of trading to at least midnight during the week and up to 2.00am at weekends. In many cases, applications for late trading are being granted despite opposition from local residents.

Government ‘should sober up’

For the Conservatives, Theresa May, Shadow Culture Secretary, complained that the Government “was in complete disarray over the implications of the new opening hours”. She said, “They knew as well as everyone else the consequences of this law. With nine out of ten pubs opening longer, it is bound to mean more drinking…..The answer is for the Government to sober up and postpone the new laws.”

Don Foster, the Liberal Democrat spokesman, echoed the call for the new Act to be delayed. “We have got a problem, and what the Government has done is make it worse, rather than tackle it.” Mr Foster said, “Ask yourself why the Government is doing this, and it goes back to the 2001 election when they asked young people to vote Labour for extra time. Now they claim the Act is about reducing binge drinking, but research shows that increasing the availability of alcohol is not the way to do that.”

For the Government, Culture Secretary Tessa Jowell defended the new Act, saying that what it does “is allow people to drink alcohol in public at a different range of times, with the threat of instant sanction if they misbehave.”

Miss Jowell did, however, condemn as “stupid” the famous text message to which Don Foster referred. Miss Jowell said the message, “Don’t give a xxxx for last orders? Vote Labour”, sent out during the 2001 election campaign, “portrayed what is in fact a serious piece of legislation intended to improve quality of life and curb crime as some kind of advert for hedonism.” Miss Jowell said, “I thought that was a stupid slogan at the time, and I still do.”

Critics of the Government are likely to point out that Miss Jowell may have disapproved of the slogan but it has taken four years for her to disassociate herself from it. Moreover, some of the key stakeholders involved in making the new system work have made it clear that it is not just the slogan they consider stupid, but the new Act itself.

Population ‘drinking itself to death’

The Liberal Democrats also pointed to another reason for delay, the release of figures showing that alcohol-related deaths had increased on average by over 18 per cent in five years, the increases being far steeper in the worst areas. At the top of the list was Yorkshire and Humberside, where alcohol deaths increased by 46.5 per cent.

Commenting on the figures, Lynne Featherstone, Liberal Democrat Spokesperson on Police, Crime and Disorder said: “These figures are deeply worrying. The Government must address the underlying reasons why people are drinking themselves – literally – to death. I am worried that the proposed change to licensing laws will add to this startling increase in drink related deaths. The Government should pause for more thought before it brings in the changes to the licensing laws in November.”

Police and Judges Let Rip

It also emerged during the summer that both the principal arms of the criminal justice system, the police and the judges, had made submissions strongly disputing the fundamental assumptions underlying the new Licensing Act in response to the Government’s proposal to establish ‘Alcohol Disorder Zones’ (ADZs) in town centres. These are to be designated areas of town centres in which police and local authorities agree that there is an unacceptable level of alcohol related crime and disorder. The basic idea is that in such zones, licensees will be required to make a special contribution to the cost of policing.

Judging by the results of the consultation exercise, the great majority of respondents from all sides of the licensing reform debate regard ADZs as an unworkable gimmick, designed primarily to persuade the gullible that the Government is being tough on alcohol related crime. This almost universal condemnation of the idea has not, of course, deterred the Government from pressing ahead with it. The Bill introducing ADZs was given its Second Reading in Parliament on 20 June.

Both the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) and the Circuit Judges attacked the proposal for ADZs. The comments of the Judges on the new Licensing Act can only be described as contemptuous.

Licensing act of lunacy

- Observations of the Criminal Sub-Committee of HM Council of Circuit judges on ‘Drinking Responsibly’ – The Government’s Proposals

- So far as we are aware we were not consulted in relation to the proposal to develop the policies which are now contained in the Licensing Act 2003. Had we been so consulted, we should have emphasised, from our experience as full-time judges sitting in the Crown Court, the inevitable explosion in alcohol-fuelled violence which in our view would have been the necessary consequence of this relaxation of the licensing regime. We note with wry amusement that, while the title of this Consultation paper is ‘Drinking responsibly’, the Home Office Minister who solicits our views entitles her letter ‘Alcohol-Fuelled Violence’. The experience if those of us who sit, day in day out, in the Crown Court is that far too much of the crimes of violence with which perforce we must deal are directly attributable to the consequences of inebriation, and the aggression and lack of inhibition which are a concomitant of that state. We set out in an Appendix a comment from one of our members in an unedited form.

- We are however in a position to comment on a passage in paragraph 4.8 of the Consultation Paper. This states: ‘Traditionally, the law and the courts have tended to regard alcohol as a mitigating rather than an aggravating factor; offenders were somehow deemed to be less culpable because they had committed their crime under the influence of alcohol than if they had been sober’. Many of us, like the primary author of this response, have been practising the law for over 40 years. It is simply untrue to state that either the law or the courts have in that period tended to regard self-induced intoxication as a mitigating factor. There is nothing in the Magistrates’ Association published guidelines to support this approach. It may suffice to refer to R v Sheehan & Moore [1975] 1 WLR 739. ‘A drunken intent is still an intent’.

- Those who routinely see the consequences of drink-fuelled violence in offences of rape, grievous bodily harm and worse on a daily basis, are in no doubt that an escalation of offences of this nature will inevitably be caused by a relaxation of liquor licensing which Government has now authorised. We regard it as simply wishful thinking to suppose that the introduction of the Licensing Act will bring about the cultural change which the Government envisages, so that binge drinking will be a thing of the past; and those who frequent the bars of our city centres will spend their social evenings limiting their consumption of alcohol to no more than will quench their immediate thirst.

- We are simply un-persuaded that the kind of culture change which this Consultation Paper envisages will ever be produced by appealing to the good nature of those who use alcohol to excess on a routine basis; or by imposing fixed penalty fines; or tinkering with the problem by identifying alcohol disorder zones, or addressing under-age drinking. The only effective way in which the problem of alcohol-fuelled violence can effectively be addressed, now that the Government has decided on the loosening of restrictions in relation to the provision of alcohol, is to make alcohol at the point of sale significantly more expensive; so that it is simply beyond the capacity of individuals who currently abuse alcohol to resort to alcohol in similar quantities. Of course we do not expect Government to heed this advice, since it would be politically unacceptable; but we make the point, as firmly as we can, so that the social and economic costs of this measure can be placed clearly in context.

John Samuels QC Chairman, Criminal Sub-Committee, Council of HM Circuit Judges 13 June 2005

Appendix

“I only try a modest amount of crime, which I do in three pretty different places. Warwick, an old county town, which takes a lot of work from SE Birmingham; Northampton, a largely ruined old county town which gets custom from itself and places like Kettering; and Oxford, which needs no description. At all three the lists contain a substantial quantity of violence, from S18 to affray, with offences often allocated with little apparent relationship to their seriousness.

It is a very rare for any of these offences of violence to be committed by someone who has not been drinking. Sometimes the quantity of alcohol is simply beyond belief. A gallon is common, 12 pints by no means rare. Often these quantities of beer are diluted by various additions of spirits. It is becoming common, too, for cocaine to be taken as well. It is not just the illiterate and inarticulate underclass which does this, quite bright people in well paid jobs do it too (with a surprising number of women). Their sole idea of fun is to get as drunk as possible in bars where this can be done as easily as possible. This is the object of their evenings of pleasure, which last as long as they have money and can find places to spend it.

Often they fight in the pubs, generally over some vestigial or imagined provocation. If not, they roam the streets in malign, short fused and generalised hostility, until some victim presents himself. Perhaps he once went out with a girl the intoxicated thug knew, perhaps he has a telephone he wants, perhaps he is simply in the way on the pavement. There follows a brief and ill expressed altercation, and then an eruption of blind savagery. Someone falls down, and he is not then left, vanquished, as an animal would leave a rival. He will be repeatedly kicked. It is quite astonishing how many survive this with only modest injury.

For a while these people are simply savages, angry, blind and brutal. They are in this condition because of what they have been drinking. They are so ill educated or made crude by inadequately civilising influences in their homes that they seem unable to drink in an acceptable ‘continental’ fashion. The more there is to drink, and the more time to drink it, they will keep drinking. If it was not for the widespread availability of alcohol I believe that crimes of violence would be at very modest levels indeed. But there is no attempt made by the government to lessen public drinking. No ‘Don’t drink and drive’ type campaigns are waged against those who drink and prowl, (and often walk into contact with cars, for which the drivers are then blamed).

The situation is already grave, if not grotesque, and to facilitate this by making drinking facilities more widely available is close to lunacy. It simply means that our town and city centres are abandoned every night to tribes of pugnacious, drunk, noising, vomiting louts. The cost to the health service must be vast, the cost to those who try to live civilised lives in urban surroundings is huge. The take by the government in alcohol tax is no doubt excellent.

In my view we should express a very high level of concern indeed, and suggest that what is needed, as a start (the subject is a large one) is a lot less provision of drinking facilities, not a lot more.”

Chief Police Officers – Government’s approach ‘simplistic and wrong’

ACPO has maintained a consistent view since the original consultation on changes to the current licensing laws. While we support many of the proposals in the New Act as a positive step forward, some aspects do cause us concern. The premise of the New Act, that the current system is rigid, enforces fixed closing times which then lead to disorder, is not consistent with what has been seen across the country. The reality is that at the current time licensed premises actually stop selling alcohol at a variety of times between 11pm and 3am, although they are able to continue to provide public entertainment beyond this, with some able to remain open until 6am and later. In our view the New Act will just shift these closing times back later into the night and condense them into a smaller time frame as closing time will be dictated by commercial pressure rather than the law.

Experience over the last decade has shown that there is a strong link between the increase in disorder and the explosion of late night premises. The assertion that 11pm closing leads to binge drinking is simply not supported by the evidence. Drinkers who want to drink later simply go to premises with a later licence or move on at 11pm to other premises that are open. It is the cumulative effect of drinking over a long period that leads people to be intoxicated on drink (although not necessarily ‘Drunk’ by criminal standards) and less inhibited and therefore more prone to anti-social behaviour and violence, and also more likely to become a victim of crime. Crime figures in effected areas show a steady increase from early evening until after the last premises closes, with no significant drop off after 11pm.

Excessive consumption of alcohol alone is not the only factor that needs to be considered. It is well established that the infrastructure around the night time economy plays a part in increasing or reducing the impact of late night drinking. Proper planning of town and city centres is vital to reduce flashpoints for disorder. Recognition of ‘Stress areas’, planning for a variety of activities and age groups, integrating fast food and an effective transport infrastructure are all vital to reduce these flashpoints. More needs to be done to ensure that Planning Authorities are truly held accountable for creating environments that reduce violence, disorder and anti-social behaviour.

Sadly our culture has become one where it is seen as acceptable to drink to excess. In fact, many young people only feel that they have had a good night out if they have drunk far too much, and peer pressure plays its part in making this view now socially acceptable, if not the norm, within certain age groups. This leads to the violence, disorder and anti-social behaviour that currently blights our city, town and village centres. ACPO has seen no evidence that supports the contention that by allowing operators to open for longer, we will see a change in this culture and therefore a reduction in violence and anti-social behaviour. One only has to look to popular holiday destinations to see the effect of allowing British youth unrestricted access to alcohol. It needs to be accepted that it is only a change in our culture that will really resolve this issue. ACPO is concerned that enforcement is being seen as the only tool that will deliver this cultural change, a view that is in our eyes both simplistic and wrong. Far more can, and needs to be done in areas such as education and product price to achieve the real cultural change that is necessary.

Much is made of the current fee for an alcohol licence being set at £10 a year regardless of the size of the premises. While this is true, more relevant is the fact that under existing legislation the larger premises, open later by virtue of public entertainment licence, have to pay a significant fee to local authorities. This is a refection of the fact that they place a greater burden on the environment than smaller pubs that shut earlier and generally cause fewer problems. The new fee structure, while providing for a small multiplier for some premises, increases the fee burden on smaller pubs significantly while reducing it on the larger operations. There is still no account of the cost of policing the pollution caused by High Volume Vertical Drinking establishments (HVVDs) and other large, drink led operations. This is an area we would like to see rectified, not through schemes such as Alcohol Disorder Zones but through a proper fee or levy system that reflects the inevitable demand that is created by these premises. ACPO remains of the view that the polluter, in this case the trade, should pay and as a result, the fee structure under the Licensing Act should be set at appropriate levels to allow it to truly pay for the costs of all administration and all enforcement activity required of all CDRP members.

Alcohol Disorder Zones

There is a general view that the introduction of Alcohol Disorder Zones (ADZ), whilst possibly complementing the existing powers to designate dispersal areas and non-drinking areas, will prove difficult to set up and maintain. ACPO is concerned that proposed zones will be routinely challenged through the courts at considerable cost to the public sector, in terms of time and money. Defending our position in the courts diverts our resources away from where they should be and does little in the meantime to reduce crime, disorder and anti-social behaviour.

There is some significant concern about how we would show that a ‘licensed premises is contributing to alcohol-related disorder’. Where that link is obvious, existing powers can be used to apply for a revocation of the licence or in the future, new powers will be available to call for a review of the licence. Attempting to geographically define an area may be similarly difficult as invariably noncontributory premises may fall within the zone and conversely contributory premises that feed the problem may fall outside the zone. History has shown us that where a direct and obvious link to a specific premises cannot be shown, the trade will seek to robustly defend their position through the courts.

Local residents try (unsuccessfully) to protect themselves The use of the new Licensing Act significantly to extend trading hours, including in residential areas, is causing considerable concern to many individual local residents and to residents’ associations and amenity groups.

The Government has of course insisted repeatedly that one of the main virtues of the new legislation is that it gives to local residents rights and opportunities to influence licensing decisions that they have never before enjoyed, – a claim which many concerned residents regard as almost wholly mendacious. A major reason for this refusal to believe Government assurances is the wording of the Guidance to the new Licensing Act which restricts the right to object to licence applications to those living or working ‘in the vicinity’ of the premises concerned. Clearly, the more narrowly the term `vicinity’ is interpreted, the fewer local residents will be allowed to object to an application, with the result that many local residents who will be directly affected by an application will be barred from making representations. Cynics have of course argued throughout that notwithstanding Government claims the new Licensing Act is systematically biased in favour of the big pub companies and applicants and against the interests of local residents. Confirmation that the cynical view is the correct one is now being provided in cases across the country in which the licensing authority is forced by the Licensing Act to disadvantage local residents. What is described as potentially a landmark case in Birmingham hinged on the definition of the term ‘vicinity’.

Bar on pub protesters Aug 17 2005

Councillors have banned residents of apartments who live 150 yards from one of the busiest pubs in Birmingham from objecting to 3am opening hours because they live “too far away”. In a landmark ruling yesterday, the city council claimed the terms of the Licensing Act 2003 prevented people living in Berkley Court from having their say about an application by the Figure of Eight on Broad Street.

Licensing sub-committee chairman Penny Holbrook accepted a submission by pub owners J D Wetherspoon that Berkley Court was not in the “immediate vicinity” of the pub and it would be unlawful to hear the views of residents.

Wetherspoon’s application to serve alcohol from 9am to 3am seven days a week at the Figure of Eight was approved by the committee. The pub has to close at 11pm at the moment.

Resident Alan Woodfield said: “I am absolutely astonished. There appears to be no rights for citizens whatsoever. “I half expected the application to be approved, but I didn’t even get the chance to say a word. “Only the other day in the early hours I was awoken by booming music from a parked car. A couple got out and proceeded almost to have sex in a doorway before driving off again.” Mr Woodfield is set to appeal to magistrates in an effort to overturn the council decision.

Coun Holbrook (Lab, Stockland Green) said: “We have carefully considered whether the interested party lives within the vicinity of the premises. It is the decision of this sub-committee that in view of the commercial premises surrounding the Figure of Eight and the guidance issued under the Licensing Act that the interested party is not within the vicinity of the Figure of Eight.”

Rachel Lynne, a solicitor representing J D Wetherspoon, said the sub-committee could only consider allegations of disorder occurring immediately outside the pub. “The guidance is quite specific and it is my submission that Berkley Court is some way from the immediate vicinity of the premises,” she added.

The Open All Hours? group has produced a leaflet advising local people of their rights to make representations under the new Act, such as they are. This is available as a printed leaflet from IAS and it can also be downloaded from the IAS/Open All Hours? web site, which now includes a new section ‘LicensingAid’.

The Licensing & Anti-Social Behaviour (LASB) working group of the London Borough of Richmond has produced a leaflet which reflects the concerns and anxieties of local residents across the country.

New licensing laws The risk of disorder and nuisance from current re-licensing

The new Licensing Act 2003 requires pubs, bars, night cafes, restaurants, off-licence outlets and entertainment venues, etc, to apply for a new form of licence, which allows them to stay open longer and vary their style of operation.

Unless an objection is made – by the police or residents, for example – then the new licence will be granted automatically.

There is now a huge risk that later closing times and other variations will add to the already serious problems of anti-social behaviour and noise disturbance experienced by the town. The licensing issues are set out below in this special edition of the FoRG Newsletter.

Over the next six weeks, all 100 licences in the town must be converted to a new licence. On a separate sheet, we describe how to object if you are concerned about a particular venue seeking to vary the hours or other terms of its existing licence.

Richmond town centre experiences a high and increasing level of alcohol-related anti-social behaviour (ASB) in the evenings. This is evidenced by recent research on the town in the Erskine Report, commissioned by Richmond Council. The research demonstrates the negative effect of ASB on the quality of life of residents, the viability of some local businesses and the enjoyment of many visitors.

Richmond now has some of the best research of any town in the country, which was crucial to the Council when, backed by the police, it unanimously decided on 14 June to introduce a saturation policy (see below) for Richmond and Twickenham town centres.

Friends of Richmond Green and The Richmond Society were instrumental in pressing for and contributing to this policy and research.

The research shows that almost 75% of residents and businesses in Richmond who responded to the Erskine survey regularly experience crime, disorder, nuisance and/or ASB linked to the licensed economy. 54% of respondents are deterred from using the facilities in the town at night for these reasons. 60% say they experience sleeping difficulties on a regular basis, linked to the licensed economy.

The problems are countrywide, but in Richmond the concentration of pubs and bars per resident is as high as in Soho. Almost uniquely, however, we have open spaces. These spaces and the diverse evening economy create a social magnet and the problem has been exacerbated by the huge growth in licensed capacity in the town (a 50% increase over 10 years) and by longer opening hours. There are now 27 pubs and bars in the centre and nearly 70 restaurants and similar venues.

Based on a report by the Cabinet Office in September 2003, we calculate the cost of alcohol-related ASB and crime in Richmond town centre is over £6 million per annum. The Licensing Act 2003 now adds an immediate and irreversible risk. It regulates most forms of entertainment, including the supply of alcohol, live music, dancing and late night refreshment. Regulated entertainment has to be licensed and applications for the conversion of existing licences have to be made to the Council by 6th August 2005 (as many as 100 in Richmond Town alone). All converted licenses come into effect on 24th November 2005. So far, the Council has received six applications varying existing licences in Richmond town centre and around 20 elsewhere. Besides the Victoria Inn and Richmond Arms, four are owned by Mitchells & Butlers plc – The Lot, All Bar One, Edward’s and O’Neill’s, The remaining applications are likely to pour in over the next six weeks.

A brief analysis of applications to date shows some worrying developments:

1. Generally, standard opening hours are being extended on Thursdays by 1.5 hours and on Fridays and Saturdays by two hours and on other days by one hour. In addition, applications are being made to add one or two hours on many specified dates – up to 17 dates in some cases. Mitchells and Butlers has also applied to open its venues for the TV transmission of ‘recognised international sporting events’ which could result in 24- hour opening for separate events in different global time zones. Licensees can also give notice of up to 12 temporary events in a year, lasting 96 hours each, with no opportunity for residents to object. Opening hours are tending to be earlier, at 10 am or even 6 am, including Sundays.

2. We estimate, based on applications to date (i.e. around 35% of capacity), that the evening economy hours from 8 pm to closing time could increase by at least 30%. This could deliver £4 million per annum of increased sales in the town – mostly alcohol consumption, which is equivalent to introducing two ‘megabars’ the size of Edward’s in the early hours of the morning, with customers moving from one bar to the next and finally trying to leave the town on non-existent public transport.

3. Some applications seem to be seeking greater outdoor activity, including live music, furthering the trend of alfresco use of the town.

4. There is a general trend to apply to remove all conditions currently attached to existing licenses – often ones we have fought hard for in the past.

5. Edward’s seeks to extend existing closing times by two hours, so that on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays it will close at 3:30 am and on other days at 1:30 am. On 17 specified dates, there will be either one or two additional hours and an application is being made to open during the transmission of international sporting events. Also, the venue will open earlier at 10:00 am on all days. It seeks to remove over 12 conditions, such as keeping doors closed. Licence variations now underway in the town could lead to there being several thousand revellers in the town at 2am or later.

Solutions to alcohol-related anti-social behaviour are not in sight. The Erskine Report made clear that concerns of residents and others are primarily with low level ASB, often in open spaces – shouting, urinating, vomiting, etc. A single incident may not be serious compared to assault, say, but cumulatively over time and when pervading an area, low level ASB is serious. It erodes the quality of life in the town and leads to an increase in serious crime.

The police have confirmed that generally they do not collect data on low level ASB. Crime statistics focus on more serious crimes, so it is essential that, in future, the Erskine type research is used to monitor the situation and inform decisions.

It is hardly practical or economical to police low level ASB on a response or re-active basis because it is often momentary, occurs at any time and pervades the town. There might be 500 incidents of low level ASB to every assault. In any event, the police are not readily available 75% of the time, overall, in the evenings to deal with low level ASB.

We are therefore seeking solutions further back in the chain of alcohol sale, consumption and consequential ASB – to deal with existing and future problems resulting from the new Licensing Act. But it is difficult to see these materialising soon.

This is of concern because we believe the extension of hours will lead to people binge drinking, with the noise and disturbance arising in the early hours of the morning when residents need their sleep. Furthermore, transport out of the town will have largely ceased by the time most licensed venues close under the extensions being applied for.

Applicants are required to state what additional steps they intend to take to promote the Licensing Act’s objectives but so far there is little to give us confidence that the licensed trade will deal with the existing problems, let alone those created by their licence variations.

Where a concentration of licensed premises exists and there is significant alcohol-related crime and disorder, the Council can add a saturation policy (known as Cumulative Impact Policy or C.I.P) The C.I.P. approved recently applies to defined zones in Richmond and Twickenham town centres and to pubs and bars (we had argued it should apply to all licensable activities). The presumption is against awarding licenses for new pubs and bars or variations to increase capacity of existing premises. Importantly, the burden of proof of no adverse impact falls on the applicant and it covers open spaces such as The Green.

We are very concerned with there being any extension of hours, given the existing problems and the risks of later opening. We will try to assist residents who wish to object to licence variations and more generally continue to seek practical solutions to the problems.

Peter Willan The Licensing & Anti-Social Behaviour (LASB) working group – sponsored by Friends of Richmond Green and The Richmond Society.

Binge drinkers: Folk devils of the binge economy

An extraordinary amount of media attention focuses on alcohol consumption and its impact on public order and health. But as Professor Dick Hobbs shows in Economic and Social Research Councils’s new report ‘Seven Deadly Sins’, while ‘binge drinking’ youths dominate the headlines, it is older drinkers that are most likely to succumb to alcohol-related death.

What’s more, Professor Hobbs argues, it is the logic of the market and not the logic derived from careful data analysis that informs government policy on alcohol. As a society, we embrace the ‘night-time economy’ – and the jobs, urban regeneration and taxation that the industry generates – while seeking to punish the routine transgressions of its primary consumers.

Hobbs notes that the term ‘binge drinking’ is rarely used to describe the drinking habits of anyone other than young denizens of the night-time economy. Binge drinking is seldom linked with alcohol-related diseases, with accidents in the home or with domestic violence. Indeed, since publication of the government’s alcohol strategy, where a binge drinker is described as someone who drinks to get drunk, the term has become a remarkably pliant device to implicate individuals perhaps more accurately described as “young people drunk and disorderly in public places”.

As such, binge drinkers are indispensable folk devils. They are noisy, urinate in public and violent. This brings them into conflict with an undermanned police force, which can be depicted on most nights of the week wrestling heroically with foul-mouthed, vomit-stained youths in an attempt to restore the city centre to daytime levels of comportment.

Despite alcohol being our drug of choice, the source is not typically regarded as a problem. Alcohol is a legal drug and so there are no attempts to bring down the ‘Mr Bigs’ of the alcohol industry. Indeed, the main dealers are ensconced with the police and politicians in crime reduction committees and urban regeneration partnerships.

Until the 2001 general election campaign, there was a general reluctance on behalf of government agencies to acknowledge problems related to the night-time economy. But Labour’s campaign that year coincided with new figures on alcohol-related assaults uncovered by the British Crime Survey, which indicated that teenage males who frequently visit pubs and clubs and drink heavily are most at risk from violent assault.

Yet government statements about the night-time economy remain guarded in relation to links with violence. This reluctance needs to be understood in the context of investment in the night-time economy running at £1 billion a year and growing at an annual rate of 10%, with the turnover of the pub and club industry constituting 3% of GDP, numbers of licensed premises having increased by over 30% during the past 25 years and the sector employing around one million people, creating ‘one in five of all new jobs’.

The night-time economy has had a transformative influence on UK cities, and is part of our society’s shift from industrial to post-industrial economic development. Successive governments have embraced this new economy as an alternative to the nation’s increasingly decrepit manufacturing base, and proud city centre shrines to our industrial past have been revitalised by shiny outlets for alcohol consumption.

The numbers of young people flocking into these new centres of alcohol consumption are unprecedented. For example, in 1997, the licence capacity of Nottingham’s tiny city centre was 61,000: by 2004, that had risen to 108,000, while Manchester city centre has a stunning capacity of 250,000.

The Labour Party signalled its intention to embrace the nighttime economy during the 1997 general election, when they solicited the student vote with text messages that read: “Cldnt gve a XXXX 4 lst ordrs? Thn vte Labr on thrsday 4 extra time”.

As the new decade progressed, the real story behind the ‘24-hour society’ began to emerge, and the concentration of huge numbers of young alcohol consumers has created environments where aggressive hedonism and disorder is the norm.

But rather than reject a major facet of their own economic policies, and recognise the night-time economy as a criminogenic zone that was having a negative impact on their own crime and social order targets, official discussion has focused on the problematic consumer in the ‘tired and emotional’ shape of the binge drinker.

Meanwhile, the Labour Party’s infamous text message has been operationalised in the form of revolutionary changes in the nation’s licensing laws. But the entire research community was opposed to the Act, citing evidence that to have an impact on alcohol-related harm, it is vital to reduce consumption by imposing more extensive controls rather than fewer. Yet despite its insistence on ‘evidence-based’ policy-making, the government’s agenda of liberalisation of the retailing of alcohol continues unabated.

High levels of mental disorder in children, and average consumption of alcohol doubles

- One in ten children aged 5-16 has a clinically diagnosed mental disorder, the most common being conduct disorder, followed by anxiety or depression, a proportion which appears to have been stable at least since 1999. However, the average amount of alcohol drunk by children aged 11-15 has increased, doubling since 1990.These findings are contained in two reports from National Statistics1. On mental health the main findings are that boys are more likely than girls to have a mental disorder. Among 5-10 year olds, 10 per cent of boys had a mental disorder, compared with 5 per cent of girls. In 11- 16 year olds, the proportions are 13 per cent for boys and 10 per cent for girls. The prevalence of mental disorders is greater among children:

- In lone parent (16 per cent) compared with two parent families (8 per cent)

- In reconstituted families (14 per cent) compared with families containing no stepchildren (9 per cent)

- With parent(s) having no educational qualifications (17 per cent) compared with those who had a degree level qualification (4 per cent)

- In families with neither parent working (20 per cent) compared with those in which both parents are working (8 per cent)

- In families with a gross weekly household income of less than £100 per week (16 per cent) compared with those with an income of £600 or more (5 per cent).

- In households in which someone is receiving disability benefit (24 per cent) compared with those receiving no disability benefit (8 per cent).

Other factors associated with an increased prevalence of disorders are lower status jobs, living in the social or rented sector and living in areas classified as ‘hard pressed’ compared with more affluent areas.

Children with emotional disorders and with conduct disorders are significantly more likely than others to smoke, drink and take drugs, the largest differences being in relation to smoking and drug taking.

Underage Drinking

In relation to drinking by 11-15 year olds, the figures for 2004 are in line with the trends of previous years. The proportion of children who report drinking did not change – indeed, in 2004 there was a 2 per cent drop compared with the previous year – but the amount consumed by children who did drink increased. The average weekly consumption of alcohol increased from 5.3 units in 1990 to 10.7 in 2004. A quarter of children who had drunk in the last week had consumed 14 or more units, an average of two or more units per day.

Reference

1. Mental Health of Children and Young People in Gt. Britain 2004. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England 2004.

Methodist HQ alcohol license application sparks abstinence debate

The Methodist Church of the Great Britain, home to the Wesleyan Movement, which influenced millions across the world, has decided to apply for a liquor licence for the church’s headquarters building – Westminster Central Hall – in central London. The move has disturbed many members of the church and raised the whole question of Methodism’s attitude to abstinence.

Westminster Central Hall has a unique place in the heart of London for it not only serves as a church hall where Christians gather for worship, but it is also designed as a well-facilitated conference centre for social, cultural and business purposes so as to serve the wider community. The revenue that comes from the rental of the premises will be directly applied to the funding of mission or social work of the Methodist Church, both in the UK and overseas.

The Rev Dr Malcolm White, a Methodist minister who was involved in drafting the application, said that over the last seven or eight years there have been many events held in the Hall where people expected to be able to enjoy a glass of wine, and therefore an alcohol licence for the cafe and some of the rooms is needed.

The managers at Central Hall expect that the sale of alcohol will provide a considerable increase in business, and as business improves, it is argued, more funds will be available for the mission or social work of the Methodist Church. Dr White insisted that the application was in line with a decision reached at last year’s Methodist Conference which said that the five churches that also provided conference facilities should be allowed to apply for such licences. The Church has debated on the application of licences since 1999.

The headquarters building of Methodism will become its first national church which is not an ‘alcohol-free zone’, if the application is successful. Methodist Church rules prohibit the serving of alcohol on Church property. It is believed that more than sixty Methodists from other parts of the country are compiling a written objection, saying that the application is in defiance of Church rules.

Beyond the application of the liquor licence itself, more concern has arisen of the attitude of Methodists to Christian abstinence. Historically, Methodists are closely associated in many people’s minds with the temperance movement. In the Victorian era when heavy drinking among the working classes was seen as one of the most potent dangers facing society, the Church was actively involved in the temperance movement.

Until 1951, the Conference made a strong appeal “to practise total abstinence from alcoholic beverages, not as a burdensome duty, but as a privilege of Christian service”. This is said to represent the peak of official support for abstinence in the Methodist Church, and after this time such support declined rapidly.

In 1987, a Methodist Conference Report on alcohol consumption ‘Through a Glass Darkly’ was released. It gave a formal recommendation to all Methodist regarding the use of alcohol. It allowed Methodists to make a personal commitment either to total abstinence or to responsible drinking.

For those who practise total abstinence, they have to take special care to avoid authoritarian attitudes which may be counter-productive; and where they practise responsible drinking take special care to demonstrate that this also involves self-control.

In addition, the Methodist Church pledged to actively engage in the promotion of responsible attitudes to alcohol and in the support (whether directly or indirectly) of those suffering the harmful consequences of their own alcohol misuse, or that of others.

Quoting from a 1999 Methodist Conference report, it reaffirmed, “Methodist attitudes to alcohol have changed significantly in recent decades from a widespread commitment to abstinence, to one in which moderate, responsible drinking is more common.”

John Wesley, who co-founded Methodism in 1739 with Charles Wesley, was not teetotal and once described wine “as one of the noblest cordials in creation”. He was, however, against the consumption of spirits.

The Methodist Church has around 300,000 members in Britain.

The Church of England, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church in England and Wales are among those churches which require communion wine to be alcoholic, and which permit the consumption of alcohol on church premises. Many Roman Catholic premises have full licences.

The United Reformed Church requires communion wine to be non-alcoholic, but permits local congregations to decide whether alcohol may be consumed on church premises.

The Baptist Union of Great Britain leaves decisions about consumption of alcohol to local congregations. Baptist churches can therefore be found in which communion wine is alcoholic, and alcohol is served on church premises.

John Beasley, a prominent London Methodist who has long campaigned against alcohol misuse and has been vocal in his opposition to this move by Central Hall, said: “This is the first time that a Methodist Church has tried to obtain an alcohol licence. Strong opposition at the court hearing will be led by the United Kingdom Alliance which highlights that alcohol is the cause of Britain’s biggest drug problem.”

Anti-binge-drinking tsar advocates binge drinking

Presumably on the basis that her Government was not receiving quite enough bad publicity in relation to alcohol fuelled yob culture, Louise Casey, the head of the Home Office anti-social behaviour unit, who reports directly to the Prime Minister, was widely reported mocking the very campaign she is responsible for promoting and advocating binge drinking to ministers.

Secretly recorded making an after dinner speech to an audience of senior civil servants, chief constables and criminal justice practitioners, Ms Casey said: “I suppose you can’t binge drink anymore because lots of people have said you can’t do it. I don’t know who bloody made that up, it’s nonsense.”

On the tape, obtained by BBC News, she said some ministers might perform better if they “turn up in the morning pissed. Doing things sober is no way to get things done,” she added.

Shadow home secretary David Davis said it was “ironic” that the official appointed to report to Tony Blair on antisocial behaviour appeared to be “an advocate of binge drinking”, and he went on to comment that perhaps this explained “why alcohol-related violent attacks are up 25% and why Labour are so keen to unleash 24-hour drinking.”

Ms Casey was appointed as director of the unit by the Prime Minister and was told to report directly to him on the issue of restoring “respect” to Britain’s streets. She is responsible for encouraging the use of antisocial behaviour orders by police and local authorities clamping down on loutish behaviour.

One of the top priorities of Mr Blair’s “respect” agenda is to reverse the tide of drunken violence blamed on binge drinkers in Britain’s city centres.

In a letter to Liberal Democrat peer Lord Avebury, who had raised the matter, Home Office Minister Hazel Blears explained that Ms Casey had been warned about her future conduct, and that “despite her light-hearted comments on the subject (Louise) is committed to working to reduce binge-drinking.” Ms. Blears did not explain if the binge drinking that Ms Casey was working to reduce included her own.

Modest lunchtime drinking markedly worsens afternoon sleepiness in drivers

Just one lunchtime drink giving an alcohol would easily pass the breathalyser test dangerous for drivers, because of its impact natural afternoon dip in mental alertness, research in the journal “Occupational and Environmental Medicine” carried out by Research Centre at Loughborough University the direction of Professor Jim Horne.

The effect is even greater for drivers who have not slept well the night before, says the research, but unfortunately, they often don’t realise just what a detrimental effect small amounts of alcohol can have.

Around one in 10 road crashes in the UK is caused by driver sleepiness, and this rate is even higher for long stretches of monotonous driving, such as motorways.

The researchers tested the alertness of 12 young and healthy men, by getting them to drive for two hours in the afternoon in a fully functioning stationary car on a simulated motorway. They chose young men between the ages of 20 and 26, because this is the group most at risk of road crashes.

The young men’s driving skills were tested after drinking small amounts of alcohol or a non-alcoholic equivalent (although participants did not know which was which), after a night of normal sleep and after a night of disturbed sleep. The research team assessed the amount of lane drift, the participants’ subjective levels of sleepiness, and graphs of brain activity (EEG – “brain waves”).

Both the afternoon dip in alertness, caused by fluctuations in the body clock and/or a disturbed night’s sleep, and alcohol independently increased the amount of lane drift, which typified road crashes caused by driver sleepiness. These effects were also registered on the brain waves and were noted by the study participants.

But sleepiness and alcohol combined, additionally and significantly worsened the amount of lane drift. While this combined impact also registered on the brain waves drivers themselves did not seem to notice the additional effect of alcohol on their sleepiness.

The authors warn that the impact of the natural afternoon dip in alertness, even after a good night’s sleep, will be worsened by a modest alcohol intake at lunchtime at levels that would pass a roadside breathalyser test.

The research was undertaken for the Department for Transport. The Government still refuses to lower the legal drink drive limit.

Binge drinking as an issue of concern

Responsible drinking’ messages are to be placed on bottles and cans of beer and spirits, though not immediately on wine, ‘to tackle binge drinking.’ The move, agreed between the Department of Health and alcohol manufacturers, and which will also extend the practice of ‘unit labelling,’ is intended by the industry to head off legislation to force it to introduce health warnings.

The Government is also planning a publicity campaign against binge drinking, probably including TV and radio advertising.

Here, Andrew McNeill comments on the importance of binge drinking as an issue of concern, and on the Government’s approach to tackling it.

Binge Drinking

Hypocrisy is a major element in the distinctive British attitude to alcohol. No southern European government would, in the perverse way chosen by the British, encourage the bars to stay open longer and longer -if possible, permanently – in order to encourage the population to drink less.

The drinking that the government says it wants reduced is heavy sessional intake. The media label this ‘binge drinking’ and Tony Blair calls it the new British disease. In reality, bingeing is neither new, nor a disease. It’s a choice. As the term has come to be understood, it is actually a culturally prescribed style of consumption practised by most young people at least occasionally, and often regularly. Of course, while bingeing is not a disease in itself it can certainly cause some severe health problems. Death rates due to acute alcohol intoxication resulting from binge drinking have doubled in the last 20 years in both men and women.

As this suggests, while bingeing has been a feature of British drinking culture for generations- there is a difference in the scale of it, and in particular in the mass public bingeing that is the economic basis of the commercialised night-time economy. This means that as well as being a culturally prescribed, if regrettable, choice, binge drinking is also a product on sale in every town centre. Other differences with the past are the fact that bingeing is now common even among the ‘underage’, and that it has ceased to be solely a male prerogative.

Binge drinking is more prevalent in Britain than almost all other countries of Western Europe except Ireland. In 18-24 year olds, only one in four women and one in six men say they never binge drink, so the great majority do so at least sometimes. In the 20 to 29 age group, 60 per cent of the alcohol consumed by women is taken in bouts of heavy drinking – defined as more than six units a day. For men of this age, half the drinking is done in heavy bouts, amounting to more than eight units a day. Bingeing is thus an integral part of the social life of most young adults.

Not only this, but overall alcohol consumption in Britain is still increasing sharply while in most other European countries it is stable or declining. In Britain, increased consumption is particularly noticeable in young women. It is true that compared to men the rise in women’s consumption started from a low baseline but that does not mean it can be dismissed as of no consequence. A recent Datamonitor report found that British women under 25 already drink more than their counterparts in other European countries and it estimated that over the next five years they will increase their intake by an additional 31 per cent, with the result that by 2009 they will be drinking more than three times as much as young women in France and Italy.

In neither men nor women does heavy drinking suddenly start from nothing at the age of 18. It begins in the teenage years, and indeed, British girls are now even more likely than boys to be bingers – a pattern that so far as we know is without precedent anywhere. Teenage binge drinkers are more likely than others also to be binge drinkers in their twenties, so the comforting idea that bingeing is merely a phase, a rite of passage, may be wishful thinking.

How much does it matter? Some suggest that public and political concern about drinking in general, and women’s consumption in particular, is unwarranted, often little more than a ‘moral panic’, a thinly disguised expression of an interfering Puritanism and, in the case of women, an attempt to deny them their new found freedom to behave as they choose.

Unfortunately, the motives of those who warn of the dangers can be dismissed rather more easily than can the dangers themselves. It is simply a statement of fact that binge drinking is causing rising levels of alcoholic gastritis, pancreatitis and liver damage especially in women, diseases that were until comparatively recently found only in men of middle age and older.

In recent years, there has been a huge amount of research into the medical and social consequences of alcohol, and one of the main findings is that the pattern of consumption matters as much, or more, than the overall amount consumed. Bingeing is a choice, and arguably it is the most unhealthy pattern of consumption it is possible to choose. For one thing, none of the supposed health benefits of alcohol is obtainable from a bingeing pattern of consumption: binge drinking does not reduce the risk of heart disease, it actually increases it. Repeated heavy drinking can lead to high blood pressure, heart muscle damage, irregular heart beat and stroke.

There are also adverse psychological effects. Bingeing, resulting in rapidly rising blood alcohol concentrations, causes a higher level of psychological morbidity, particularly in the case of anxiety and neurosis, than even the same amount of alcohol consumed more steadily over a longer period. Again, these effects are more pronounced in women.

As might be expected, the adverse effects of bingeing are particularly evident in the young. Repeated high blood alcohol concentrations are particularly bad for teenage brains, with obvious implications for learning capacity and memory. Teenage bingeing has been linked to impaired mental and social development, reduced school performance and attainment, and increased likelihood of school exclusion. It is not surprising that the subtitle of a recent publication aimed at youth, sponsored by the American Medical Association, was ‘Drinking makes you stupid’. Early introduction to alcohol, particularly binge drinking, increases the likelihood of heavy drinking and alcohol problems later in life.

Then there are all the other social problems linked to bingeing, such as consumption of illegal drugs, crime and antisocial behaviour. There is, for example, a close relationship between bingeing and undesirable or undesired sexual behaviour. Alcohol is quite certainly the biggest date rape drug, and high proportions of first sex and unprotected sex take place while the participants are drunk. In this connection, given what is known about the effects of alcohol on the reproductive system and on the foetus, there are some obvious and disturbing implications of the popularity of binge drinking in young women of childbearing age. Here, as elsewhere, it is not just that there are problems in the here and now, it is that they are also being created for the future.

What to do?

Government initiatives fall under three main headings: a new Alcohol Licensing system; an Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy, and the Public Health White Paper. These encompass a large number of measures, some of which are sensible, but there is also a great deal of naivety and, more cynically, a good deal of playing fast and loose with the evidence. The idea, central to the new Licensing Act, that the principal means of countering binge drinking is the abolition of the system of permitted hours was promulgated in spite of the evidence rather than because of it. The idea, favoured by the Alcohol Strategy, that alcohol education in schools is the answer to the problem similarly lacks any convincing evidential base.

The Government is now planning an anti-binge drinking advertising campaign. The issue here is the same. – evidence, or, rather, the lack of it. There is no known example of a publicity campaign of this kind bringing about any measurable reduction in the incidence of binge drinking. Such campaigns may be of benefit in the sense that they draw attention to the issue, and they may even affect people’s attitudes towards it, but it is simply naïve to expect them to bring about any sustained change in what people actually do.

In contast, the evidence on the value of controls on the fiscal and legal availability of alcohol was discounted in the Alcohol Strategy. For example, there is good evidence that one of the most effective ways of reducing bingeing and violence – the main cause of public and political concern – is to increase the price of alcohol. A one percent rise in the real price of alcohol could be expected to result in up to 5,000 fewer assaults in England and Wales. Unfortunately, the Government rejected this as an approach.

Similarly, in relation to young people, the evidence is clear that what we need is a concerted policy of delaying the onset of regular drinking in childhood and adolescence, not naïve attempts to teach them to drink ‘sensibly’.

But, of course, measures such as delaying onset and tax increases are politically more difficult, and certainly deeply disliked by the alcohol industry.

In regard to national policy, therefore, the root of the difficulty lies in the Government’s heavy reliance on forming a partnership with the alcohol industry, a policy likely to be a very mixed blessing indeed. As evidence of the benefits of this approach the Government will point to the recently announced initiative of the British Beer and Pub Association purportedly to put an end to ‘binge drink as much as you like for £10’–type promotions among its member companies. Unfortunately, what is proposed falls a long way short of the billing and it does not begin to tackle the features of the market that give rise to these promotions in the first place.

The larger picture suggests that it is very unwise to place the alcohol industry in such a privileged position that it has almost a power of veto over national policy. Binge drinking, after all, is dangerous and destructive to both individuals and society, but it is also extremely profitable.

Parents not peer pressure responsible for binge drinking

A significant link has been discovered between the extent that parents encourage drinking and both drinking frequency and intensity, challenging the view that peer pressure is mainly to blame for the increasing levels of alcohol consumption amongst young people.

The research, which was carried out by Dr John Marsden and colleagues from the Institute of Psychiatry, was published in the September 2005 issue of the British Journal of Developmental Psychology.

The study involved 540 students aged 15-16, both male and female. Participants were asked to complete a structured questionnaire which recorded alcohol involvement, other substance use, perceived parental alcohol use and related factors, alcohol related attitudes and beliefs, psychological well-being, social and peer behaviours, and school conduct problems. Two follow-up questionnaires were administered at 9 and 18 months following recruitment.

It was found that there was a significant link between the extent that parents were seen to be encouraging drinking, and both drinking frequency and intensity. More frequent parental discouragement to drink was also related to more frequent drinking in females but to less frequent drinking in males, suggesting that either there is a tendency for girls to rebel more strongly against their parents attitudes towards alcohol use, or that parents are more likely to disapprove of drinking in their daughters, and hence discourage alcohol more strongly. On average the participants were 14 years old when they first drank without parental knowledge.

The research also discovered that a number of young people drink to alter their mood with 51% of participants saying they drank to relax, and 34% drinking to forget about a problem. Social reasons for drinking were also important with 63% drinking to enjoy company of friends, and 48% drinking to lose inhibitions. By the age of 13 most young people have consumed a whole alcoholic drink, and by 15 two-fifths drink every week, with many consuming 4.7 units on a typical drinking day.

Dr Marsden said, “The potential feasibility and benefits of including parents as part of education programmes in school should be examined. The possibility of encouraging parents to consider how their own behaviour and attitudes towards drinking might influence the choices regarding alcohol use that are made by their offspring should be explored. Given the high prevalence of drinking involvement in mid-adolescence, understanding the influences on the further development of drinking attitudes and behaviours is of critical importance”.

The authors argue that the research underlines the importance of addressing personal, family, peer and school conduct factors in school-based alcohol education programmes.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.