In this month’s alert

World Cup fouled by drink and violence

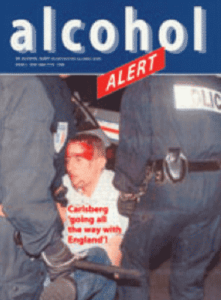

The lottery of a penalty shoot-out may have brought England’s World Cup campaign to an end, but it was the violence of drunken fans which marred the opening. The newspapers blazoned photographs of football supporters swilling beer, hurling missiles at rivals, conducting running battles with the French police, and generally causing mayhem. Reports stated that they were usually drunk and the pictures tended to confirm this. Television footage rarely showed a fan without a can or bottle, possibly the product of a World Cup sponsor, in his hand and as often as not failing to meet the challenge of communication.

The continental press was quick to pick up the theme. Following the disturbances in Marseilles, the Italian newspaper, La Repubblica, allowed itself some free-ranging comment: “Look at these people, with their stomachs hanging out, tattooed from top to bottom, peeing on people on the ground, too drunk to remember their names and addresses at the police station…it’s their ignorance of life which is so terrifying.” This was “the ignorant side” of Blair’s Britain, the paper claimed, the real face of the country. La Repubblica drew attention to the fact that some sociologists had sought to excuse the hooligan behaviour by saying that these young men were the direct descendants of those who fought at Waterloo. Considering the Duke of Wellington’s opinion of the soldiers under his command (he thought they were “the scum of the earth”), this might be an accurate comment in more senses than one. The Italian reporter becomes hyperbolic (if that is not risking a national stereotype), describing the fans “with two fingers raised, trousers down, bare-buttocked, with a burning desire to see blood run – these were all too typical of British behaviour”. The hooligans who are so roundly condemned probably believe that all Italians belong to the Mafia.

But La Repubblica makes a telling point: “The popular tabloids may write about shame, yet the same rags pay some hothead’s expenses so that he can publish his diary of how he screwed the police and devastated every bar in sight.” Newspapers like The Sun have entertained their readers for years with xenophobic headlines encouraging the attitudes which led to scenes such as those witnessed in Marseilles. “The Sun today calls on its patriotic family of readers to tell the feelthy French to FROG OFF!”

The German press was interested in contrasting the Cool Britannia image which the Prime Minister is trying to project with the “crude counterpoint of collective violence, uninhibited vandalism, and racism”, as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Germany’s most distinguished newspaper, put it – with unintended irony in view of the subsequent behaviour of German fans. “They conformed to the common picture of English football fans: tattooed contemporaries with ambitions only to drink the remaining pathetic dregs of reason out of their skulls and to supply their own team with a backdrop of permanent intoxicated rioting.” The reporter, continuing in sententious vein, states that the hooligan – a word of Irish origin, as it happens – “is a particularly English creation, drawn from the working class, whose natural habitat is the pub and whose intellectual horizon is confined to an overwrought, usually racist and far Right stew of half-baked ideas.” This latter combination of qualities must have seemed uncomfortably familiar to older readers of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

The question, of course, remains as to exactly how widespread the violence was and what was its cause. Given the number of English supporters who travelled to France, it is quite clear, as the Sports Minister, Tony Banks pointed out, that only a small minority were involved. The vast majority of English fans were well behaved and entered fully into the spirit of the occasion. This is confirmed by the reaction of bar owners and restauranteurs in Toulouse, Lens, and Saint Etienne as well as the authorities. It is, of course, understandable that attention focused on the troublemakers and shocking that such behaviour disgraced the national effort. But it must be kept in mind that a complex series of factors influenced events: the reputation of British fans, the reaction of the French police, the existence of tough North African gangs in Marseilles where England played Tunisia, the activities of groups interested in violence rather than football, the desire of the media to report sensational events (and the willingness of the inadequate to provide them when in the presence of a camera), and, of course, the ubiquitous influence of alcohol. This last stemmed from the relentless promotion of the sponsors’ products, the refusal of the French authorities to restrict the opening of bars, the regular involvement of a number of players in highly publicised drunken sprees, and the association in the minds of many between any sporting event and the consumption of vast quantities of beer.

There are such clear and well-established connections between alcohol and violence that it may seem odd to some that those who have the responsibility for security at large-scale sporting events tolerate its promotion and widespread availability. The French Minister of the Interior said that he did not think that his country should have to change its way of life simply to guard against the excesses of unruly visitors. Even after the events at Marseilles, the decision was taken that there should be no change in the bar opening times in the run-up to the England-Argentina game, other than that they should close at 11 pm having been open since eight in the morning. However, there was a complicating factor in this question, in that, since most English fans did not have tickets to get into the game, the bars were the only places where they could watch it on television and so be kept from causing trouble on the streets. The bars being closed would, of course, not have prevented their acquiring alcohol.

The alcohol industry had staked a huge amount on the advertising potential of the World Cup. Sponsorship does not flow from any philanthropic view of life, but from hard-headed business reality. Anheuser-Busch put millions of dollars into the event in the knowledge that its investment would be repaid many times over in increased sales. Presumably the same motive led Carlsberg to sponsor the English team, perhaps mistakenly expecting a longer run than from its native Denmark. The big problem facing the industry in the World Cup was the Loi Evin, by which it was illegal for any advertisement for alcohol to be seen on French television: hence the sponsors could not use hoardings around the football grounds where they would have been caught on camera during matches. The brewers complained to Brussels that this was an infringement of the free market. The European Union, however, maintained that it was a public health matter not one concerning the freedom of the market. The industry was willing to go to considerable lengths to get round the Loi Evin simply because they knew what vast sums of money were involved in their advertisements being seen during matches. In this context, it was interesting to note the opening film used as an introduction on BBC television. This swept the viewer through the doors of a splendid Parisian restaurant and, as the camera panned around the interior, footballers appeared: Gascoigne sobbing, Bobby Moore holding the Jules Rimet trophy aloft, then others, projected in bottles or onto the surface of glasses of wine. A neat association, unconscious perhaps, between alcohol and the World Cup was made in a way which would have been illegal as an advertisement on French television.

According to other reports in the press during the World Cup, violence was not always associated with alcohol, and alcohol was not always associated with violence. Most Scottish fans may not have drawn a sober breath during their stay in France, but their behaviour throughout was benign. This may have had something to do with the difficulty of being taken seriously as a belligerent when sporting a ginger wig and Tam O’Shanter. On the other hand, the neo-Nazi gangs from Germany, which caused their government such shame and left a French policeman struggling for life, were marked by their sobriety. Alcohol may often cause violence, but it makes it less efficient. It also invites violence: it is by no means unusual for a drunk to be beaten up by sober assailants and this seems to have happened during the World Cup disturbances.

Whatever the causes of the violence which damaged England’s reputation during the World Cup – and they were certainly complex – alcohol played a major part. Since the unpleasant elements which actually commit the violence are unlikely, without prolonged therapy, to address the problem of their character defects, the governing bodies of football cannot avoid looking at the question and debating the issue of sports sponsorship and the availability of alcohol seriously. Major sporting events have become closely associated with alcohol to the detriment of their good name and the enjoyment of a majority of fans. More importantly, a dangerous message is being sent out to young people.

Alcohol, violence and the law

The problem of rising violence is linked to the easier access to alcohol which youth now enjoys.

This was the view expressed by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Paul Condon, in a recent interview in The Independent. He pointed out that young people have more money and a greater choice of places to drink. Sir Paul also blamed today’s drug and rave culture, a view which is also discussed in the newly published report by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Here the comment is made that “deeply felt anxieties about the effects of popular entertainments on the morals of young people have been expressed in Britain (sic) since early Victorian times.” Such attitudes, the report suggests, should be seen in their historical context.

The Commissioner said, “Where I think there has been a real increase is violence between young people linked to drink…It is about the relative affluence of young people and their ability to drink and club.” The Home Office’s chief criminologist concurs with him in blaming the nationwide rise in assaults, at least in part, on the greater number of people who can afford to drink excessively. This is in accord with a Home Office study published in 1990 which showed that crimes of violence tend to increase with prosperity, specifically with the enhanced ability of young men to buy beer and visit pubs and clubs. Indeed, the study found that growth in beer consumption was the single most important factor in explaining growth in violence against the person.

Police statistics show an annual growth in crimes of violence every year for the last decade. In Manchester, for example, there was a huge 50 per cent increase in such offences during the last year, and in 1997 they constituted 8 per cent of all crime. In London, against a background of an overall drop in crime, there was a 6 per cent upsurge in violent offences.

Whilst, on the one hand, the Home Office is expressing concern at this trend, it is also reviewing licensing laws with the possibility of introducing new laws to allow all-night drinking by the turn of the century. A variety of interested parties, including representatives of the police, brewers, local authorities, and magistrates has claimed that support is growing for this measure.

One tactic which Sir Paul’s own force, the Metropolitan Police, is considering is “naming and shaming” pubs and clubs which have a reputation for violence. One police station in central London is planning to release the names to the press and report pubs with a high incidence of violence to the brewers, presumably on the assumption that they would wish to avoid adverse publicity and consequent loss of custom. Sir Paul believes that such schemes will become common as soon as the new Criminal Justice Act comes into force. This will oblige all police forces and local authorities to take crime reduction into consideration in their strategic decisions.

If the Commissioner and the chief criminologist’s views of the situation are correct, then they may come into some degree of conflict with Home Office minister, George Howarth, who is leading the move to modernise licensing laws, or help “blow away the cobwebs in British life” as he puts it. Echoing his Tory predecessors, Mr Howarth said that the current licensing laws “no longer reflect modern leisure activities or the needs of business.” He was speaking at a lunch given by the British Institute of Innkeeping whose members welcomed the idea of liberalising the law as it stands at the moment.

“Our first task is to examine the current system and come up with practical proposals for change which will command wide support from both the public and the industry,” said Mr Howarth. “Paramount in drawing up proposals will be balancing the rights of business and consumers with residents’ rights to be free from disorder and violence, or other kinds of disturbance. This will be a major task and will take time if it is done properly.”

Workers in public health question what consumer rights could be better served by the opportunity to drink round the clock. The advantages to the industry are more apparent.

A statement issued by the Home Office said that all licensing issues would be looked at “including what type of licences there should be, who should licence(sic), licence hours and conditions, the process of issuing them and their enforcement.” At the present time magistrates grant licences in England and Wales, whereas in Scotland this is done by local councils. In the light of the continued increase in alcohol-related violence, the likely consequences of changes to any part of the licensing laws will also need to be a major consideration.

Reeling spires

Cambridge students marked the end of final examinations with a drunken binge which caused chaos at the city’s renowned Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

A male nurse was assaulted, other staff threatened, and everyone present subjected to a torrent of foul language. “Suicide Sunday”, as the day set aside for celebrations is wittily known, culminated in a vast drinking session at Grantchester Meadows. Every available ambulance was called to the scene and nine people were taken to hospital, eight of them Cambridge undergraduates and one a student from Bristol who was the victim of an assault. Police made a number of arrests.

The director of accident services at Addenbrooke’s, consultant surgeon Howard Sheriff, said, “Getting drunk and nasty in Marseilles has its parallel in Cambridge, irrespective of education. They threatened staff and assaulted one of the male nurses. Their language was unforgivable in front of young children already in the department.” Mr Sheriff was equally unimpressed by the attitude of some of the students’ parents whose attitude, he said, “was no less irresponsible when we contacted them. They wanted us to find rooms for them to stop them wandering the streets or ending up in police cells.”

The welfare officer of Cambridge Students’ Union, echoing the excuses put forward in certain quarters for the criminal soccer thugs in France, said that “hard-won exam results are a justified cause for celebration in every university at the end of the year.” Condemning the drunken students, in what some of those at the receiving end might regard as half-hearted and contradictory terms, Elliot Vaughn added that “actions which impact (sic) on the whole community in this way are wholly indefensible and regrettable.”

A spokesman for the University of Cambridge said that it “very much regrets the inconvenience and distress caused by the drunken behaviour of the students.”

Alarming trends in youth drinking

The amount of alcohol drunk by young people continues to grow – in the case of younger teenagers by as much as 40 per cent over a four year period – and the most popular venue for consumption is the home. These findings are in Young People in 1997 , part of a series of surveys carried out annually by Exeter University’s Schools Health Education Unit.

Over 37,000 pupils between 8 and 18 years old are involved in the research and their responses show general increases in consumption. Among children aged 15-16, for example, boys now drink on average ten drinks a week compared to seven in 1993, whilst girls have gone from five drinks to eight.

The largest proportion of children’s drinking takes place in the home. Over 15 per cent of boys aged 11-12 (9.7 per cent among girls) did this as opposed to 4.4 per cent (1.8 per cent for girls) using a public place. In the case of Year 11 pupils , that is,15-16 year olds, almost 45 per cent of both sexes drank in their own home, substantially more than in any other place. The second choice of drinking venue was a friend’s or relation’s home (27.7 per cent boys, 31.1 per cent girls). Clearly the vast majority of these young people consume the bulk of their alcohol in private houses where it might be assumed their well-being was the responsibility of adults who were their parents or the parents of their friends. The same trend is shown among all the other year groups surveyed.

Given the significant number of children and teenagers drinking at home, the question of parental knowledge arises. Answering the question, “If you ever drink alcohol at home, do your parents know?”, over 52 per cent of Year 5 pupils – children of 9-10 years of age – said that they did. No indication is given of frequency of consumption and in some cases this may be no more than one glass of wine on special occasions. For reasons which are unexplained, the figures vary in response to this question: just over 39 per cent of 14-15 year olds said they had drunk at home with their parents’ knowledge, whilst 47.5 per cent of 13-14 year olds gave the same answer. Presumably a proportion of the parents involved are attempting to inculcate an attitude of “sensible drinking” in their children. There is evidence, such as that recently gathered by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in the United States, which indicates that children who begin drinking alcohol regularly by the age of 13 are more than four times more likely to become alcoholics than those who delay consumption until they are 21 or over.

Off-licences are the most popular source of alcoholic drink for Year 10 pupils (14-15) but by the next year the pub has taken over. Supermarkets have the lowest level of patronage, possibly as a reflection of the greater care being taken at the check-outs to prevent sales to under-age drinkers.

When questioned about quantities, just under 10 per cent of 15-16 year olds were drinking more than the maximum levels formerly recommended by the government of 21 units per week for adult men and 14 for women. Even taking the different cultural and sociological factors into consideration, the NIAAA research would suggest that these young people are in danger of developing problems. They are certainly vulnerable to the many dangers of binge drinking, such as alcohol poisoning, violence, serious accident, and unwanted sexual encounters.

Advertising effects

More than a third of young smokers said that advertising had played a large part in their decision to use cigarettes. The argument put forward by cigarette manufacturers – and by the drink industry – is that advertising is simply a matter of redistribution, of persuading those who already smoke or drink to change brands.

The survey found that 71 per cent of those who said they were occasional smokers were influenced by adverti-sing. Contrasting the claims of producers with the survey findings, researcher Dr Dave Regis, said, “The actual effect [of advertising], in the opinion of the young smokers, is different. Other surveys have suggested that young people are affected by tobacco advertising. Now this is the evidence of the youngsters themselves.”

Complacency

Whether parents facilitate their children’s drinking or not, they tend to show a disproportionate level of concern at illicit drugs as opposed to alcohol. Workers in the field believe that parents need educating in the dangers associated with youthful drinking as much as their offspring. “At least he’s not on drugs,” seems to be the most often expressed sentiment when it comes to teenage alcohol misuse.

A tragic loophole

In the last edition of Alert the case of David Knowles was reported. He was the 14 year old boy from Pudsey in Yorkshire who was sold lager and alcopops in a Thresher off-licence and was then killed whilst running across a busy by-pass. Readers will recall that because of a loophole in the law, no-one could be prosecuted for selling him the alcohol. The staff involved were on the national pay-roll of Thresher and therefore not the servants of the licence holder as defined by law. This could mean that thousands of people working in off-licence chains can sell alcohol to minors without fear of prosecution. The licence holder himself could only have been prosecuted if he had been the one to carry out the sale.

It added considerably to the grief of David’s parents to know that no-one would be held responsible for providing the alcohol which led to his death. John Knowles, quoted in the Daily Express, said, “If alcohol is sold to children then it is obvious to every right-thinking person that they could do damage to themselves, to others, or to property, and yet there is nothing to stop people selling to them either out of carelessness or just to make a profit.” He added that his son “might have got away with looking 15 in a bad light, but he was obviously under age.”

A spokesman for Thresher, whilst acknowledging that David’s death was a tragedy, called for the introduction of identity cards. “Every day staff are being asked to make judgements on how old people are,” he said. “It is phenomenally difficult.” There are clearly those who might think this was an overstatement when the customer in question is a youthful looking 14 year old.

Paul Truswell, the Member of Parliament for Pudsey, took the case up and introduced a 10-Minute Rule Bill with the intention of removing the loophole by substituting “agent” for “servant” in the relevant clause of the Licensing Act . This would have the effect of making anyone working in an off-licence or supermarket liable to prosecution in cases such as that of David Knowles.

10-Minute Rule Bills introduced by backbenchers are a means of bringing an area of particular concern to wider notice and have no chance of becoming law. However, the Minister of State at the Home Office who has responsibility for these matters, George Howarth, has assured Mr Truswell that the law will be amended. The Home Office is at the moment preparing “a wide-ranging review of licensing” but a spokesman, referring to this particular case, said, “this is more urgent and will be considered more speedily.”

Speedily enough to prevent more tragedies being caused by the sale of alcohol to children, it is to be hoped.

Death by misadventure

In another tragic incident in November 1996, teenager Graham Bailey was killed by a train after drinking several bottles of the alcopop Hooper’s Hooch and six pints of lager. All these drinks were served to the fourteen year old boy in the Swan Hotel in Scarisbrick, Merseyside. Graham was attending a party in the pub’s function room to celebrate the 15th birthday of a friend. The group was eventually asked to leave because of rowdy behaviour and a number of them walked towards a nearby railway line. Graham was with another teenager when the barrier came down, trapping them. His friend managed to avoid the oncoming train but Graham was struck and killed.

Edward Moorcroft, then licensee of the Swan Hotel, admitted 18 offences of serving alcohol to under-age drinkers and allowing children under 14 into a bar. Magistrates fined him £6, 410 and his wife £1,410 and removed his licence. At the time police called for controls on the sale of alcopops.

The case is back in the news because Graham’s parents have taken out a private prosecution for manslaughter against the Moorcrofts. Magistrates at Ormskirk have set a second hearing for 1st September.

Mr Bailey, also called Graham, said, “We are prepared to lose everything to get justice. All the children in Graham’s group were between 13 and 17. They should not have been served with alcohol. I could accept it if Graham had got away with being served a glass of lager but he was drinking all night.” Mr Bailey said that, whilst he was aware that his son was at a party in the pub, he assumed that the landlord would not allow the children to get drunk. “It has been established that Graham drank six pints of lager that night. Many a grown man could not hold that much drink.”

Landlords and breweries, as well as the managers of off-licences such as the one which served David Knowles the alcohol which led to his death, will be watching the progress of this case carefully. The outcome could have considerable repercussions in the trade.

Booze, fags and smack

Alcohol and tobacco are linked with the use of illegal drugs, it is unequivocally stated in a major new independent report, Drug Misuse and the Environment, published by the Home Office.

Speaking at the report’s launch, Home Office Minister George Howarth, said that it “paints an accurate and rounded picture of the complex social problems linked to drug misuse.”

The authors, who make up the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, accept the findings of various surveys which show that the use of alcohol and tobacco are predictors of the use of illicit drugs. “If society intends to provide young people with an environment which helps them not to take illicit drugs (or abuse volatile substances), or to reduce the harms which they do, the climate of awareness and belief on alcohol and tobacco must be seen as part of that context.”

Attention is drawn to the problem of children drinking alcohol (Alert passim ): “Many of the studies on young people have identified significant proportions consuming alcohol…Most recently there has been concern over the availability of a number of alcoholic drinks, which in aspects of their marketing, and in some cases their sweet taste, may particularly appeal to young people – these drinks include a variety of white ciders and fruit wines. It has been shown that many of these drinks are being widely consumed by those under 16.”

The report draws attention to the vital fact that for “many young people alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs inhabit one and the same world rather than constituting separate domains.” The need to consider the influence of the general view of legal drugs on illegal drug-taking behaviour is stressed. “There is clear evidence from US data that early use of licit drugs increases the risk of developing patterns of illicit drug use at a later stage. The majority of people who have used illicit drugs have previously used tobacco and alcohol. Similarly those who have never smoked or consumed alcohol rarely report use of illicit drugs. Alcohol and cigarette smoking have been found to be the most powerful predictors of marijuana use for both females and males and the relationship strongest where the cigarette smoking had begun before the individual was aged 17.”

The tendency to demonize such “dance drugs” as ecstasy or amphetamines whilst condoning the use of alcohol is acknowledged as dangerous. “Young people live in a society which heavily advertises alcohol and tobacco, and where they are readily and lawfully accessible, and the advertising of “alcopops” has on occasion seemingly been targeted at young people and has at times veered towards open encouragement of drunkenness.”

The report recommends that Drug Action Teams, one of which is located in each Health Authority, tackle alcohol misuse alongside drug misuse. “When setting up drug prevention policies consideration will often need at the same time to be given to the place of alcohol, tobacco and volatile substances in the scheme of things. Drug prevention policies which ignore licit drugs lack credibility.”

In the section of the report which sets drug misuse in its historical perspective the authors state that in the nineteeth century in England alcohol was ‘the major substance problem… and there is vivid contemporary testimony as to the appalling social consequences of slum drinking which were embedded in social deprivation of an extent and intensity which is today fortunately long since gone. The more privileged sectors of society at the same time also drank heavily.’ It was in these circumstances of extreme social damage that the temperance movement grew up, championed by such diverse figures as Cardinal Manning and Keir Hardie. It is all too easy to assume that the alcohol problem has been removed, or at least been substantially ameliorated, by greatly improved social conditions. What this report makes clear, is that it has merely changed its nature. At the same time, the connexion between illicit drug use and social deprivation is emphasised.

From ‘6 o’clock swill’ to 24 hour trading. Liberalization and control of licensing hours in New Zealand

by Linda Hill

Alcohol & Public Health Research Unit, Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine & Health Science, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Legislative control over the sale and supply of alcohol, and the way legislation is implemented, has important consequences for the health of individuals and for society as a whole. The regulatory framework helps create the social climate and physical environments in which we drink, and can influence the extent of alcohol related harm. In 1989 New Zealand’s traditionally restrictive regime was overturned by a new Sale of Liquor Act. Liquor licences are now readily obtained by a wider range of premises. Hours of trading are set licence by licence, and may permit 24 hour, 7 day a week availability.

Liberalising licensing

Tension between the social pleasures and the social consequences of alcohol are part of New Zealand’s political history. High levels of drunkenness among a disproportionately male colonial population helped produce a strong temperance movement around the turn of the century, and liquor licences for very restricted hours of trading became the main mechanism for state regulation of the sale and consumption of alcohol. A result of this was the ‘6 o’clock swill’, an all-male ritual of rapid beer drinking between ‘knocking off’ work and close of trading, which continued until 1966. Under the 1962 Act, it had to be argued before a Licensing Control Commission that any new liquor outlet was ‘necessary or desirable’ to meet the requirements of the public. By the mid 1980s commentators were pointing out that, while this restrictive regime recognised the need to control distribution of a potentially harmful substance, its effect had more often been to provide for economic regulation and protection of the liquor industry. Restricting the market in alcohol had created local monopolies, and licences themselves had become saleable commodities, transferable between localities.

It was this market in licences, dominated by the two main breweries, that was dismantled by the Sale of Liquor Act, 1989. Under the new regime, licences are granted to any applicant with planning consent unless shown to be ‘unsuitable’. As a consequence the market for alcohol as a product has expanded and become more competitive but, as stated in the object of the Act, continues to be subject to ‘a reasonable system of control with the aim of contributing to the reduction of liquor abuse’. In fact, regulation of some aspects of management of licensed premises was increased, in particular through a requirement to provide food and non-alcoholic drinks and reporting on premises by local inspectors, police and public health/health promotion officers. In the cities café-bars, licensed as restaurants, have replaced most of the old-style hotels and taverns, with the breweries moving out of pub ownership to focus on sales of beer, spirits and some wines, including retailing through their own off-licence chains.

Hours of trading

Restrictions on hours of trading were also overturned by the 1989 Act. Previously ‘usual hours’ of taverns and hotels were limited by statute to 11 am to 10 pm, but the then local licensing committees could from time to time extend these hours if ‘in the public interest to do so’.

Under the 1989 Act daily hours of trading are set for each licence on application by the licensee and are entirely at the discretion of the Liquor Licensing Authority, which replaced the old Licensing Control Commission. An extension of these hours can be obtained in the form of a ‘special licence’ for a particular occasion.

Pubs and off-licences may not sell alcohol to the public on Sundays and on certain public holidays, but restaurants may – and the liberalised licensing regime has greatly increased the number of restaurants which have liquor licences. A distinction is made in licences allowing sale for consumption on the premises between ‘taverns’ whose primary business is selling alcohol (with entry restricted to those over 20) and ‘restaurants’ that may sell alcohol only with meals (to anyone over 18 or with a responsible parent, guardian or adult spouse). This contributes to the popularity of licensed cafes, which tend to blur this distinction in ways which taverns consider unfair. Restrictions on Sunday trading may be removed by legislative amendments later this year.

Initially, in the new deregulatory climate, applications for 24 hour licences were granted and trade organisations encouraged licensees to apply for these whether or not they intended to use them fully. An early Authority decision set the scene nationally by granting a licence to 3 am.

By mid 1993 the Authority recognised that: ‘the extension of hotel and tavern closing hours from 6 pm to 10 pm [in 1996] and subsequently to 1 am or 3 am over a 26 year period has been too drastic a change to sit comfortably with some local authorities, community boards and citizens – especially in some smaller communities.’

As a rule of thumb, 3am is now being considered a reasonable closing time for most premises in areas zoned for commercial use. Hours of trading are the only matter on which the Authority may consider neighbouring land use. Where neighbours lodge an objection the Authority is likely to set a closing time between 11 pm and 1 am. In smaller towns licensees are frequently not interested in working late hours for little return. In the cities and larger provincial towns, premises trading as nightclubs are likely to seek and be granted a closing time of 5am or later. In the large city centres inspectors report a limited number of 24 hours licences, not all of which make full use of those hours. Those which do are likely to be the well-run international hotels, or premises seeking a late night advantage in what is now a highly competitive market.

Problems from late night trading

Location of drinking is an important predictor of alcohol related harm. In New Zealand, hotels, taverns and clubs are the licensed venues in which young men do most of their public drinking. A third of the heaviest drinkers are young men aged 18-24 and this group reports most problems, such as getting into a fight or drink driving. In many districts police charge sheets for drink driving (and in some areas for all offences) ask where the last drink was taken, as a way of identifying ‘problem premises.’

In most modern cities, a peak in violence and road trauma occurs shortly after midnight. Research in Western Australia has shown that assaults in ‘taverns’ peak earlier than late night dance premises, which in turn peak earlier than those in private settings. When closing times are delayed, crime and road crash peaks are delayed to a similar degree. In New Zealand, five years on from the liberalisation of licensing hours, random breath alcohol testing has helped reduce drink driving. In interviews in 1995, however, some police reported experiencing not just a delay but an increase in street disorder associated with late opening premises. In their view, drinking over longer hours was resulting in increased levels of intoxication, and increased problems requiring police attention. As one licensing sergeant expressed it: “The publican kicks them out, shuts the door, that’s the end of his problem. We’ve got to deal with the fights as they meet going from pub to pub, wilful damage as they throw beer bottles through windows, they’re so drunk that they just urinate in a doorway.”

However, some police saw a positive side to premises now remaining open until 1 or 2am. With later closing times, young people in particular tended to go out later. Previously when the pubs closed at 11pm, young men had gone on to drink at private parties, where police had little right to intervene. Now, police noted, they remained longer in a controlled environment and were then usually content to go home.

Closing times now differ from licence to licence. Some police preferred not to have all drinkers coming out onto the street simultaneously, but most referred to the problem of the ‘migrant drinker’. As one pub closed, patrons would move on to another with later closing hours. The last opening tavern was likely to attract already intoxicated patrons. Some less profitable and poorly run premises sought later hours of trading in order to attract this business, and were likely also to be associated with serving minors.

It is widely asserted that problems arise when premises are poorly managed; late night hours of trading should not be considered a problem in themselves. Health promotion officers offering ‘host responsibility’ training to managers and staff point out that profits are to be made by providing a safe and enjoyable social experience, and by providing food and entertainment as well as alcohol. This is certainly the direction of many successful premises under the liberalised licensed regime. In the view of one public health officer, however, changes in the style of many premises under the new Act represents an extension of market opportunities, rather than changed behaviour in all New Zealand drinkers.

Australian researchers have noted that most violence in and around licensed premises involves young, single males who may enjoy watching or taking part in violence and street disorder. Such a ‘top night out’ is likely to be sought at places with late hours of trading.

Cutting back trading hours of problem premises

Hours of trading are one of a limited number of set and discretionary conditions which the Authority may attach to a licence, which are not open to review by the High Court. The principle underlying the new Act was that licences should be ‘easy to get, easy to lose’, but in its first years the Authority was reluctant to suspend or cancel licences, as this would deprive licensees of their livelihood. This was partly because the Act allows appeals against Authority decisions and until an amendment in 1996 trading could continue until the appeal was heard. It was also because the Act did not make clear provision for minor sanctions. Over the years, however, the Authority has developed ways of responding as flexibly as possible, within the framework of an Act designed to limit the extensive discretionary power held by the previous Licensing Commission.

Hours of trading are the area of greatest discretion allowed the Authority. Statutory officers found that an application to cut back the hours permitted by a licence was the most effective means of dealing with premises associated with problems such as selling liquor to minors, serving intoxicated persons, disproportionate representation on the local last drink survey, or complaints from neighbouring residents and businesses. In some cases, loss of late night hours was reported to have led to closure. Such an approach had considerable merit, given that first two licence cancellations, for extremely unsatisfactory late night bars, took two years to achieve.

Planning local licensing hours

In a number of localities, community concern about the longer hours of trading for licensed premises has made liquor licensing a town planning issue in local politics.

District plans already restricted hours of retail trading in residential zones to 11 pm, which for licensed premises was in line with the ‘usual hours’ set by the previous Act. Shortly after the new licensing Act, another new Act, the Resource Management Act 1991, introduced a new planning regime. The key criteria for granting a liquor licence are licensee suitability and planning consent. The Liquor Licensing Authority and legal commentators see the Sale of Liquor Act as primarily concerned with how licensed premises are managed, and consider location to be a planning matter. It is a purpose of planning to anticipate any impact on local communities, and to take their wishes and concerns into account. However, planners have not been accustomed to consider the sale of liquor in planning the development of local communities. District plans tend to regulate future land use by zones, whereas issues of concern to a community may relate to a particular site.

Under the Sale of Liquor Act objections may be made by individuals with ‘a greater interest than the public in general’ to the suitability of the licensee or on those limited grounds that the Authority may consider in setting the terms of the licence. As noted, the Authority may consider neighbouring land use only in relation to hours, but not whether the licence should be granted at all. Nor may it set licence conditions in response to concerns, other than those listed in the Act. In its first years, the Authority tended to grant the requested hours and advise objectors to present evidence of adverse effects or unsatisfactory management at the time of renewal. More recently, it has used its ability to set hours of trading as the only means at its disposal to respond to the concerns of neighbours. In its 1996 and 1997 reports to Parliament, the Authority expressed a wish to respond to the social concerns expressed by objectors but said it was powerless to do so satisfactorily. It asked legislators to consider allowing it discretion to refuse a licence on grounds other than licensee suitability, and to extend criteria to consideration of the object of the Act – that is, contributing to the reduction of alcohol related harm.

Dissatisfaction with these processes has led to political agitation in a number of localities about hours of trading and the location of licensed premises. Pressure from the public and local police has led a number of councils to adopt policies on maximum hours of trading for licensed premises in commercial as well as residential areas. Provided such policies are adopted by the full council, these are now respected by the Authority, in anticipation of incorporation into a District Plan. New District Plans are gradually being formulated under procedures laid down in the Resource Management Act but, as objectors are finding, planning consent for a pub or bottlestore cannot be denied unless the sale of liquor is a business activity which is specifically restricted by the District Plan. This may be done by making the sale of liquor ‘a notifiable land use’, meaning that an application for planning consent would trigger a public hearing. The provisions in the Resource Management Act on public notification and public objection are wider than those in the Sale of Liquor Act. The only improvement suggested by a 1996 review of the Sale of Liquor Act was a requirement for a public notice on the site be as well as in the local newspaper.

Conclusion

The liberalisation of licensing under the 1989 Sale of Liquor Act has led to change, not only in the number, but in the style of public drinking. The present focus on the way premises are managed offers opportunities to reinforce server practices which research has shown to be effective in influencing levels of intoxication and behaviour. Legislative amendments in late 1996 and additional ones scheduled for late 1998 or early 1998 to clarify and strengthen the Act are likely to enhance regulatory credibility. Whether other liberalising proposals – to lower the drinking age from 20 to 18-with-ID and to allow all premises to trade on Sundays – will survive the Parliamentary ‘conscience vote’ process remains to be seen.

The response of a number of communities to extended hours of trading is salutary. It is clear that many New Zealand communities do not regard alcohol as just another product, and the sale of liquor as just another business activity.Despite being administered and enforced at the local level, the 1989 Act makes little provision for control over licensing decisions by local communities. But a wish for such control remains. Where objections to late hours of trading, the siting of premises, and other concerns do not meet a satisfactory response, local concerns may be displaced to another arena of decision making which offers opportunity for local community control.

| Open all hoursIn the UK round the clock drinking has been proposed by the Better Regulation Task Force, chaired by the newly- ennobled chairman of Northern Foods, Chris Haskins. (see back page Alert comment).

George Howarth, the Home Office minister, has already stated the need for a overhaul of the licensing laws and will take the task force’s views into consideration when he issues the document outlining the government’s thinking in the autumn of 1999. Lord Haskins condemned the “high moral tone” of the present laws. Mocking the idea that it was all right to be served an alcoholic drink at 10.15 pm but not an hour later, he said, “Putting everybody out on the streets at 10.30 pm just means that in the previous 45 minutes people drink too much.” The experiment of 24-hour opening has already been tried in New Zealand. In her article we publish here, Linda Hill, of Auckland University, explains the pitfalls of such a scheme. |

A century of pioneering

The idea of a total abstinence association attracting youth may seem unlikely nowadays, but in many parts of the world that is exactly what the Pioneers are doing. Young people in Ireland and in African Commonwealth countries continue to be attracted to the idea of putting aside the use of alcohol, despite – or perhaps because of – the pressures they are under to drink, from the media, advertisers, the industry, friends, and, as often as not, parental example. The widespread use of illegal drugs may also prove a spur to some of the young to show a practical concern for the problems of addiction.

This is the centenary year of the Pioneers, the crusading Irish total abstinence movement founded by Father James Cullen. The culmination of the celebrations will come with a huge rally in Croke Park, Dublin, on Trinity Sunday, 30th May, 1999.

Father Cullen, a member of the Society of Jesus, had taken the pledge himself in 1874. He had been greatly moved by the harm caused to so many families by the drunkenness which was so prevalent in the Ireland of his day. He also believed that any hope of political and religious liberty lay in national sobriety: “If Ireland be sober Ireland shall be free.”

At first, like other campaigners before him, he made his appeal to those who abused alcohol. Even when the numbers who came forward to take the pledge were high, the newly reformed tended to lack perseverance. Father Cullen put his mind to the problem of establishing a means of supporting those who had taken the pledge of abstinence so that they could be an example to others and an encouragement to those who had no control over their drinking. The thought came to him that a “heroic sacrifice” made by people who did not have an alcohol problem might act as a support to what he called “our weaker brethren”.

At a meeting with four good Dublin ladies on 28th December, 1898, Father Cullen outlined his plan. They responded with enthusiasm and the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart was born. Since that day the organisation has spread throughout the world and helped countless thousands avoid the harm caused by the abuse of alcohol. Pioneers abstain for life from intoxicating drink. The “Heroic Offering” is made for the sake of others, not so much as a pious example but as an offering to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a continual prayer on behalf of those who experience the pain of addiction or abuse, and a union with the suffering of Christ. The Sacred Heart is an aspect of Jesus Christ which sometimes causes confusion to non-Catholics. Put very simply, just as the human heart has always been seen as the seat of the affections, it is the symbol of His love and it is where He suffers the pain of man’s sin. Father Bernard McGuckian, S.J., the present Central Director of the Association, in his book, Pledged for Life, gives a lucid and detailed explanation of the devotion to the Sacred Heart and its relevance to the work of the Pioneers.

“The motivation for [the Pioneers’] choice is rooted in Catholic spirituality,” says Father McGuckian. ” In this perspective, drink like everything else created is good. Evil is always derivative and only arises with the abuse of something good. The Pioneer believes that moderation in drink is a good thing but to give it up for a high ideal is a better thing. This is a simple extension of the understanding of fasting in Christian tradition.”

Father Cullen’s main inspiration was Holy Scripture. The impulse of the Christian to be concerned for the well-being of his fellow man was central to the purpose of the Pioneers: ” [The] life and death of each of us has its influence on others.” (Romans, 14:7). However, the most distinctive mark of the Pioneers since the inception of the Association was devotion to the Sacred Heart, as exemplified by the badge worn by every member. In his book, Father McGuckian explains : “This devotion was revealed to St Margaret Mary Alacoque at Paray-le-Monial. She taught that three specific benefits for the human family would follow from widespread devotion to the Sacred Heart: sinners would find an ocean of mercy, tepid souls would become fervent, and the already fervent would rise quickly to great perfection.” By happy coincidence, as the Pioneers celebrate their first hundred years, next summer sees the centenary of the act which Leo XIII considered the most important of his pontificate, the consecration of the whole human race to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The founders of Alcoholics Anonymous also saw the necessity of employing spirituality in recovery from addiction. The twelve steps of the AA programme of recovery unconsciously echo the Twelve Steps of Humility which St Benedict describes in Chapter VII of The Holy Rule, written in the sixth century, which will have been familiar to St Margaret Mary. In accepting a spiritual dimension to recovery, whether it be specifically Catholic like the Pioneers or left to the perception of the individual, as with AA, the drinker acknowledges his powerlessness over alcohol and the necessity of trusting in God – or a higher power, as AA puts it. Father Cullen’s primary concern was the victim of addiction and he prayed that the Pioneers “would win from Heaven by the gentle violence of total abstinence the conversion of excessive drinkers.” At first Father Cullen’s words seem puzzling, but, as Father McGuckian points out, he is alluding to Christ’s words about the Kingdom of Heaven suffering violence and, in the words of the old Douai version, “only violence bears it away.” It is as if the prayers and offering of the Pioneer wrest from Heaven the grace which the addict needs to overcome his addiction.

Although the Pioneers may never have been quite the force in England that they have been in Ireland, they have made a huge impact in African countries of the Commonwealth. “It is like what it was in Ireland in the first half of this century,” says Father McGuckian. A feature of education in the UK is the strength of the Catholic schools. Their ethical basis is attractive to parents who have no connection with the Church and there is often considerable competition too find a place on their lists. It is perhaps among these young people that the Pioneers might find the best opportunity for growth.

The Catholic Church is in the process of canonising a number of Pioneers; that is, recognising that they are saints. The Venerable Matt Talbot is probably the best known. At the age of 28, in 1884, after a life dominated by subservience to alcohol, he took the pledge and was given the strength to conquer his addiction. Not only did Matt Talbot manage to achieve sobriety but thereafter led a life of the greatest sanctity and prayer. He died on his way to Mass in his native Dublin on Trinity Sunday, 1925. At the stage of the canonisation process where a person is declared Venerable, they are recognised as having practised the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity as well as having the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. From the ranks of the Pioneers, there are also the Venerable Edel Quinn and the Servants of God, Father John Sullivan, S.J., and Frank Duff.

On of the most prominent Pioneers of recent years is Cardinal Cahal Daley, familiar the world over for his efforts for peace in Northern Ireland. His Eminence, who always wears his Pioneer badge, said this about the Association and its founder: “Father Cullen sets his standards for membership high and he was uncompromising in his demands for fidelity to those standards. He was more concerned about the quality of the commitment than he was about the large numbers of members. He expected nothing less than heroism from Pioneers. Let there be no misunderstanding, however. Pioneers do not set themselves up as a spiritual elite, or think of themselves as heroic persons. They simply see themselves as freely choosing a certain form of self-denial as one of their ways of ‘taking up their cross every day’ and following Jesus Christ. Devotion to the Sacred Heart, particularly under the aspect of reparation to the Sacred Heart for the pain caused to the Heart of Christ by sins of intemperance, were and are an integral part of the spirituality of the movement and the main source of its motivation. It is not primarily by human means, however admirable in themselves, that the Pioneer Association hopes to counter the evil of drink abuse, but rather through the ‘folly of the Cross of Christ’.”

In his book, Father McGuckian draws attention to the “truly inspired summary of the role of the Pioneer in society” given in a Papal audience by His Holiness Pope Paul VI in 1974: “We exhort you to continue in your praiseworthy efforts to help eliminate the disorder of alcoholic abuse from society. This is done by prayer and the sacrifice of abstinence which you gladly offer to God by a compassionate awareness of the complex physical, psychological, moral, and religious aspects of the disorder itself. We earnestly hope and pray that you show to all whose lives are affected by this grave problem may indeed serve to strengthen the moral fibre of society and bring closer to it the healing and sustaining hand of Christ the Saviour.”

Pioneers throughout the world are responding to this exhortation as they have done for the last hundred years.

Pledged For Life by Bernard J. McGuckian, S.J., may be obtained from Pioneer Publications, Dublin, 27, Upper Sherrard Street, Dublin 1, Ireland.

Snug as a bug

With perfect timing Hope UK has produced its new Drug and Health Education Guide for 5-7 year olds. This is the age group which had drawn the attention of the Drug Tsar, Keith Hellawell, and for which teachers are badly in need of material. They do not need to look much further than Snug as a Bug. The book is attractively produced, spirally bound for easy classroom use, and divided into six clearly-marked sections. Each section has useful, entertaining activities to engage the interest of young children.

Hope UK provides high quality resources and training for school, churches, youth and children’s organisations, and parents on the issue of drugs. More information about Snug as a Bug and their other publications can be obtained from: Hope UK, 25(f) Copperfield St, London SE1 0EN,

Tel 0171 928 0848, Fax 0171 401 3477.

Alert Digest

Yellow card in the sky

British Airways are considering introducing a “yellow cards” system for disruptive passengers as the increasing number of drunken incidents on aircraft is causing concern that one might lead to tragedy.

Alcohol Concern has called for an end to the distribution of free alcohol after reports confirmed that assaults on staff and damage to cabins had increased fourfold since 1994. It has also been suggested that a limit be placed on the amount of alcohol which can be purchased.

A spokesman for BA said that a move to end free drinks or limit purchases would “spoil the enjoyment of millions because of the actions of a tiny minority.” The UK Flight Safety Committee said it hoped the authorities were not waiting for a crash before taking action.

MPs attack smugglers

Members of Parliament are demanding that people caught smuggling drink and cigarettes across the Channel should lose their driving and haulier’s licences. They are also asking Customs and Excise to act on removing the liquor licences from places selling illegally imported drink and to be more vigorous in bringing prosecutions against the smugglers themselves. As we go to press Dawn Primarolo has announced that the Government is to give an extra £35 million to Customs and Excise to tackle alcohol and tobacco fraud which is losing the Treasurery over £800 million each year.

Alcoholic livers

28 patients out of 59 who had alcoholic liver disease took up the glass again after receiving transplants. This was shown in a survey carried out at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham.

Transplant surgeons are pointing to this evidence to support their policy of urging alcoholics waiting for liver transplants to sign an agreement that they will seek help to overcome their addiction. So far 28 patients have made the promise and accepted the counselling which is on offer.

A spokesman for the hospital said, “We want them to understand that having a new liver won’t cure them if the reason for having the transplant is alcoholism. But we don’t stop people from having a new liver if they do have alcoholism.”

£15 to oblivion

A Sheffield pub offered a “drink all you can” session for £15 which led to the death of a 25 year old man. Scott Woolhouse was killed after falling downstairs. Judge Patrick Robertshaw said that the alcohol he had drunk at Scandals pub contributed to his death. The judge added that licensees should behave responsibly in selling drink to the public. “The evidence indicates a very high degree of irresponsibility on the part of those responsible, the pub. Those responsible for the premises on this particular night were quite clearly not in the business of providing leisure entertainment. They were making a clear pitch aimed at young people with one thing and one thing only in mind and that was to become very seriously drunk indeed. ”

For his £15 Mr Woolhouse had drunk a pint of lager, 4 bottles of Budweiser, 2 alcopops, and approximately 18 measures of spirits.

Roadside justice

It is time for the police to have the power to charge suspected drink-drivers at the roadside, said Ken Williams, Chief Constable of Norfolk, addressing the annual conference of the Association of Chief Police Officers. Mr Williams believed it was necessary to move towards “evidential breath-testing, where suspected drink-drivers could be dealt with at the roadside and a positive test would result in an instant charge and bail for court the next day”. He said: “Roadside evidential breath testing could speed up the way in which drink-drivers are dealt with and save some police resources.”

Mr Williams, the vice-chairman of the ACPO’s traffic committee, said such testing may be appropriate for “most cases”. However, some might still have to be dealt with at police stations – such as when the driver opted to give a blood sample, or when there was impairment by drugs or a refusal to give a sample. In any event, a device for roadside testing which provides evidence acceptable in the courts is being developed.

Mr Williams reiterated the ACPO’s call for a reduction in the blood alcohol limit to 50mgs per 100 mls. He also said that the Association also wanted a change in the law to allow police to test drivers without their being conditions such as involvement in an accident or the commission of a moving traffic offence. He said: “In other words, there are no pre-conditions for requiring a breath test. This is not a plea for random testing but a call for a clear general power for police to breath test any person reasonably suspected of being the driver or rider of a motor vehicle who is either impaired through drink or drugs.” Mr Williams said this would “permit the intelligence-led targeting of individuals in the high-offending groups”.

The ACPO has argued for a long time that the hard core of drink-drivers can be identified and should be actively targeted. Mr Williams wanted accurate intelligence to be gathered “on known drink-drivers and the locations they frequent…Clearer legislation combined with this accurate intelligence could have a significant effect on the ability of police to combat the drink-driver.”

Alert Comment

A poor piece of work

The loophole highlighted by the tragic case in Pudsey needs urgently to be closed. In this case, the off licence that sold alcohol to a 15 year old boy, who later died, escaped the legal consequences because it could not be proved that the staff who served the boy were the `servants’ of the licence holder in the sense required by the legislation.

The loophole should be closed by injecting an element of corporate responsibility into licensing law, preventing unscrupulous operators from avoiding liability when their staff break the law. This is one of the recommendations of the Better Regulation Task Force*. It is a very sensible recommendation. Unfortunately, this is about as sensible as the Task Force report gets.

The main thrust of the report is the alleged need for fundamental reform of English and Welsh licensing laws, which are `outdated and bureaucratic’. The most eye catching element of the package of reform is 24 hour opening of pubs and clubs.

The most obvious deficiency of the report is the inability or unwillingness of the authors to provide any argument or evidence to support their proposals. This may not be too surprising given that with one possible exception, no member of the Task Force has any recognised knowledge of the subject.

In regard to 24 hour opening, for example, Lord Haskins, the chairman of the Task Force, stated in the press release launching the report: “There is ample evidence to demonstrate that a single closing time creates rather than controls nuisance and disorder.”

Readers would however be wasting their time looking for any of this ample evidence either in the press release or the report, as not a scrap of it is provided. Nor is there any indication of where it might be found. Moreover, Lord Haskins’ assertion should be compared with (for example) the experience of Edinburgh, where “substantial reductions in drink-related crime and disorder appear to have resulted from the reimposition of restrictions on late night opening and the reintroduction of set closing times.” Neither does the experience of New Zealand (reported in this issue) provide clear support for 24 hour opening, to put it mildly.

The Task Force assert that a broad consensus exists for licensing reform, including 24 hour opening. In reality, the consensus exists largely within the restricted circles of the alcohol and leisure industries and a minority of drinkers. Up to now, no Government has believed it to be in the public interest to introduce such reforms, and with good reason. One reason is that all the indications are that the majority of the public are opposed to change. The Task Force choose not to mention the fact that the previous Government was unable to extend drinking hours by a mere 1 hour on Friday and Saturday nights because of strong public opposition.

Another main purpose of the report is to attack the licensing magistrates for being `unduly restrictive’ and `inconsistent’ from one part of the country to another. The Task Force does not consider the possibility that conditions vary from one area to another, and therefore that what is appropriate in one may not be in another: it just demands that responsibility for liquor licensing being transferred to local authorities. No reason whatever is given for believing that local authorities would be less inconsistent: in fact, given that they, unlike licensing magistrates, have to be directly responsive to public opinion because they are elected, they are probably more likely to be inconsistent.

An example of the `undue restrictiveness’ of licensing magistrates is, apparently, their outrageous insistence in relation to children’s certificates that food and non-alcoholic drinks be available in bars which admit young children. Readers of Alert may judge for themselves whether it is magistrates or the Task Force who are out of touch with both the realities of things and – an element ignored completely in the report, – public opinion.

This report is likely to exert considerable influence over Government policy. It was, after all, produced at the Government’s own request and it is distributed by no lesser body than the Cabinet Office. It is a matter of concern, therefore, that it is such a poor piece of work.

* Better Regulation Task Force. Review of Licensing Legislation. Cabinet Office. July 1998.

This time it’s personal

And I have known the eyes already, known them all –

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

The lines from Eliot’s “The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock” came to mind when I began to look through the third edition of the well-known and influential Problem Drinking* by Nick Heather and Ian Robertson. I have a personal, subjective difficulty with this book. Scientists like to categorise and one of the problems of addictive behaviours, including alcoholism, is that they largely defy categorisation. There is no neat scientific explanation for a vastly complex subject which seems to involve the whole man, mind, body, and soul. That last word would condemn me in the eyes of writers such as Heather and Robertson. It brings an element into the debate with which they feel uncomfortable and to which they demonstrate hostility. But the real personal difficulty with Problem Drinking is that it is an insult to my recovery.

The authors first aim is to debunk the disease theory of alcoholism and promote the theory that alcohol problems are “best seen as examples of socially learned behaviour”. It is an aim I should have applauded when I was first in treatment. It seemed to me that the therapists and counsellors looking after me were trying to feed me a lifeline, to provide an escape clause from responsibility. It also seemed at odds with the idea of “triggers”, those situations or emotions which lead the alcoholic to pick up a glass. The danger was that, in presenting a front of noble acceptance of responsibility, in asserting the efficacy of my will and masking the fact that I had no control over alcohol. This would have left open the possibility of returning to moderate drinking (which, for me, was a memory of about a fortnight when I was fifteen). It is a stage many people go through in the earliest stages of recovery.

With certain reservations, I can now accept the word disease because it just about fits the circumstances. Given the definition which is strictly medical, it is perhaps unfortunate that the word was used in the first place. Some exponents of the disease model, it is true, speak as though it were established scientific fact, which is clearly nonsense, and which provides ammunition for opponents like Heather and Robertson. The word is a rough and ready way of describing a sufferer’s experience of addiction to alcohol. The writers correctly draw attention to one of the original aims of those who first promoted the disease model of alcoholism: the lifting of labels such as “morally flawed” or “weak-willed”. In other words, precisely that abnegation of responsibility which I objected to in the drunk farm. Heather and Robertson are probably right when they say that this aim has not been wholly successful. In my view, this is because it is proposing a simplistic solution to a bafflingly complex problem. Addiction does not remove responsibility for actions, any more than a hyperactive libido excuses rape, but it does offer an explanation. Plenty of people suffering from alcoholism may not be able to control their drinking but are still able to make moral choices. Standards may fall, but a total collapse of values is by no means usual. I think other sufferers understand this.

There’s the rub. It is quite clear that the authors do not have a problem with alcohol themselves. They may have a considerable understanding of those parts of the subject which can be fixed “in a formulated phrase”, but they do not seem to have any insight. This can come from the experience of dependent drinking itself and it can come from empathy.

A great deal of research which supports the theory that alcoholism is a socially learned behaviour is brought forward in Problem Drinking. However, when it comes to scientific evidence, the authors are at times happy to base their argument on some dubious sources. The research carried out at the Maudsley Hospital by D.L. Davies and published in 1962 as Normal Drinking in Recovered Alcohol Addicts is quoted as a reliable authority. This study by Davies, for all the caution he urged, was the foundation of the controlled drinking movement and as such has had a profound effect. Professor Griffith Edwards, at one time Director of the National Addiction Centre at the Maudsley, showed Davies’ work to be false. Davies’ research was based on 7 patients and Edwards followed these up after one of them reappeared at the Maudsley. “By then [the early 1980s], one of the original 7 had died. The conclusion of the later follow-ups was that 5 of the 7 had in fact shown evidence of alcohol misuse both during the period of Davies’ original follow-up and subsequently. Two of them were later readmitted to hospital for alcoholism treatment; the spouse of the third expressed concern over the amount he was drinking and his hospital notes described him as ‘a well known alcoholic’ six years after he was reported by Davies to be drinking without problems. The medical notes of the fourth referred to his drinking too much and to his wish for further treatment at the time of Davies’ original follow-up. The fifth in fact drank heavily with problems, especially marital ones, soon after his original discharge.” Of the two other patients, one does not seem to have been a full blown alcohol addict whereas the other’s claim to be drinking without problems could not be confirmed and at a later follow-up he refused to give a blood specimen but did smell of alcohol in the middle of the afternoon.**

Professor Edwards’ comprehensive demolition of Dr Davies’ shoddy research highlights a pertinent point and one which applies to other more thorough pieces of work. Can anyone take seriously as a source of scientific data information supplied by an alcoholic (alcohol addict, or what you will) who is claiming, or even genuinely trying, to drink normally? Ask anyone who actually suffers from the disease (God pardon the mark!) and you will be laughed to scorn. To be fair to the authors, they categorically state that they do not recommend experiments in controlled drinking to alcoholics, but it would not be surprising if some careless reader took it otherwise. It is argued that controlled drinking is an option for non-dependent drinkers who have begun to develop problems with their misuse of alcohol but have not yet shown sign of full-blown alcoholism. In other words, alcoholism is avoidable by an exercise of the human will. There is no way this view can accommodate the concept of powerlessness which is explicitly stated in the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

I should not have felt qualified – other than as a sufferer – to comment on this book had Heather and Robertson not showed such animus towards Alcoholics Anonymous. There is a lot which irritates me about AA: the ghastly little sayings, the evangelical fervour of a few individual members, the “12-step Nazis”. But the fact remains, that it works. Heather and Robertson may sneer at the lack of scientific evidence of its efficacy, but they miss the point. There may be all sorts of reasons why the AA approach works for so many (one of which may well be self-delusion), but if alcoholics are able to stop drinking and change their lives, then these are secondary. Of course, there are thousands of people who have tried AA and rejected its approach, a great many, I have no doubt, because they do not really want to stop drinking. In what can only be described as their attempts to minimise the significance of AA, Heather and Robertson suggest that members “differ from other kinds of problem drinker in personality.” Now, this is no doubt true, if they mean that the personality of the addict is distinctive in some way from everyone else, including people who have lesser problems with alcohol, but clearly what they are getting at is something different. “AA appears more suited,” they say, “to those of a more authoritarian type of personality who see things in black-and-white terms and who enjoy belonging to groups that provide a clear structure for understanding the world.” Oh dear! what sad, foolish little prejudices inform this kind of statement. Such nonsense undermines all their other views and any claim to scientific objectivity. AA contains the most disparate group of people I have ever come across. Some, of course, do not have a complex outlook on life, others display the most sophisticated attitudes. No doubt there are some who like black-and-white solutions, but these are equalled by those who view any question as a shading of grey. It would be absurd to say that “the authoritarian type of personality” is a stranger to AA, especially as a compulsive desire to control seems to be one of the traits of an alcoholic. Changing this, it appears not to have occurred to the authors, is part of the point of being in the organisation.

The founders of AA make no great claim to originality – hardly surprising when advocating a programme of common sense and honesty. When I first got to know the the 12 Steps, I telephoned to a friend who is a monk. “These things are just the spiritual life of the Catholic Church,” I said. He agreed and directed me to Chapter IV of The Rule of St Benedict which contains the 12 Steps of Humility. I mention this in the hope of irritating Heather and Robertson, armed as they are with prejudices about authoritarian figures who see things in black and white.

The authors use the term “12-step hysteria” to describe the proliferation of variants of the programme. Hysteria is a pejorative term. Heather and Robertson do not like the 12 Steps because this is where God comes in. God means a host of different things to AA members, many of whom were intensely hostile to the idea when they first became associated with the organisation. As it happens, using the 12 Steps in recovery deepened my Catholic faith and allowed me to turn to God in prayer in a way that had been impossible when addicted. Friends in AA whom I love and respect have the greatest antipathy to organised religion, but are themselves using the Steps, as often as not with much greater application than me.

The whole idea of a spiritual dimension to the problem can be a huge stumbling block but the fact is that simply refraining from alcohol is only the first step towards recovery. It is necessary to change the whole person and change those aspects which are part of the addictive personality, if I might use another contentious expression. Members of AA and the proponents of any 12 Step based programme would say that it is no use simply stopping drinking if the result is living as a dry drunk. I had an acquaintance who did just that. He boasted that, without any kind of treatment and without following any kind of programme, he had not had a drink for nearly a year. Unfortunately, he was the same manipulative, dishonest, grandiose, self-pitying, emotionally constipated wreck that he had been when on a bottle of malt a day. At least when he was drunk he passed out occasionally. Many similar examples come to mind.

Heather and Robertson would condemn such stuff as anecdote. Anecdote is a very bad thing and is used as an offensive synonym for experience. It is something else which is not “sprawling on a pin.” My experience tells me that the 12 Step programme alters people’s lives. I have seen it countless times. My experience is replicated with everyone who has entered recovery through AA. To condemn this experience or the spiritual aspects of the programme as unscientific is like criticising Tower Bridge for being an inadequate tunnel.

The ideological disputes within the world of alcohol problems make Byzantine theologians sound like like-minded friends sharing anodyne views on uncontentious topics and Heather and Robertson do their manful bit to keep them going.

* Problem Drinking, Third Edition, Nick Heather and Ian Robertson, Oxford University Press

** Alert, April 1995; Griffith Edwards, D.L. Davies and “Normal Drinking in Recovered Alcohol Addicts”: the Genesis of a paper. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 35 (1994).

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.