In this month’s alert

Industry targets the young

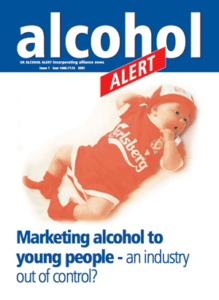

“Scandal as drink bosses target our children” was the headline in the Daily Express. The article was inspired by the recent Eurocare publication, “Marketing Alcohol to Young People”, an eye-catching brochure which brings together examples of advertisements from all over the world. The text shows how the drink industry cynically sets out to persuade the young to consume alcohol by making it appear glamourous, fashionable, and amusing. The advertisements associate alcohol with sporting and sexual prowess. Heroes of the football field play with the logo of a particular beer emblazoned across their chests. Beautiful young women imply a willingness to surrender to the man who swills a particular kind of booze. Perhaps most notoriously, there is the Carlsberg baby – a child of a few months who, in the colours of Liverpool FC, is already a living advertisement for Carlsberg lager.

It was this last image which caught the attention of Gro Harlem Brundtland, the Director General of the World Health Organisation, at the recent ministerial meeting in Stockholm on Young People and Alcohol. Holding up the brochure, she said that this was evidence of what governments concerned about the well-being of youth were up against.

Besides the Daily Express, other major national newspapers took up the story, as did television and radio. The industry was perhaps unprepared and could only come up with the comment that “Marketing Alcohol to Young People” was “inaccurate and misleading” though the various spokesmen could hardly deny that the advertisements were genuine and spoke for themselves. “Self-regulation is working,” said the industry’s Portman Group and it is true that a number of complains have been upheld but these have been against such flagrant violations that they could hardly be ignored without the system being totally discredited.

Those working with the problem would say that what is much more insidious is the relentless pressure exerted by the kind of advertising strategies highlighted in “Marketing Alcohol to Young People”.

The fact is that problems arising from alcohol use among the young are rising, particularly in the United Kingdom, and there is a vast consequent cost to the NHS – besides the terrible personal price many families have to pay. At least the Portman Group is happy with how things are going on the self-regulation front.

Ironically on the day “Marketing Alcohol to Young People” was reported in The Daily Telegraph, the same newspaper announced a “ground-breaking” appointment at Bacardi-Martini, one of the Portman Group’s major funders: a marketing director with special responsibility for “the youth market” and audiences at musical events.

Open All Hours – City centre communities matter

There is continuing anger and alarm at the Government’s proposals for licensing reform (see Alert, No.2, 2000). The likely adverse effects on the quality of life for city-centre residents and visitors were discussed at a conference held in London recently. In particular, concern was expressed at the injustice entrenched in the White Paper which virtually gives the entertainment industry a free hand whilst tying the hands of local residents.

In his introduction Matthew Bennett, the organiser of the conference and a Soho restaurateur, highlighted the problem:

“The recent growth in the leisure, food and drink industry in relation to the night time economy is clearly popular with some people, especially the young. However, many of those who live in the central core are finding that a number of adverse impacts, late night noise, litter, street fouling, drunkenness, drug dealing and crime and disorder have been unpleasant side effects.”

The former Secretary of State for Health Frank Dobson, MP, whose Holborn and St Pancras constituency includes Soho, where there are more licensed premises than in all central Paris and Frankfurt combined, sent a message of support to the conference echoing Mr Bennett’ comments: “It seems clear to me that late night opening of any but the most respectable and quiet premises encourages drug pushing and drug taking if only it leads to the presence of larger numbers of young people on the streets.” He went on to say that he and Karen Buck, the MP for Regent’s Park and North Kensington had had a meeting with Jack Straw, the Home Secretary, to call for what amounts to the opposite of the Government’s own proposals – “tougher licensing laws to help make central London safer and more pleasant at night.”

The two backbenchers pointed out that most “of the problems come from alcohol which contributes to 40 per cent of violent crime, 80 per cent of assaults, and 90 per cent of criminal damage.” They told the Home Secretary that, whilst they welcomed the proposal to bring together under local councils the licensing of both alcohol and entertainment, they believed that this should be taken as an opportunity to crack down on loutish and dangerous behaviour. Jack Straw accepted the MPs’ contention that the proposed powers of the police to close immediately for twenty four hours “any licensed premises from whence (sic) disorder spills out on to the streets” should be extended to cover serious nuisance as well.

Frank Dobson put forward the view that councils “as licensing authorities should be able to reject alcohol and entertainment applications on the grounds that a particular street or locality is ‘saturated’ with similar users. Councils could be expected to formulate licensing policies, as they had to do with planning policies, and then apply those policies to every licence application.” Mr Dobson stated that the Home Secretary was sympathetic to this idea. If this means that it will find its way into law then it marks a significant departure from the proposals as set out in the licensing White Paper, where it is assumed that every individual application must be treated on its merit with a presupposition of a favourable reception irrespective of the number of other outlets in the relevant area. licensing policies.

The answer hangs on the interpretation of the word “sympathetic” which could simply mean, “I understand your concerns and even share some of them but have no intention of doing anything about them”.

Rather than clear up this important issue, the video message sent to the conference by the Home Office minister with responsibility for licensing, Mike O’Brien, confuses it further. He says, “We envisage that, under the White Paper proposals, each local authority would develop an overall licensing policy for its area, providing a framework within which decisions on individual premises could be assessed.” The licensing authority would then consider any application taking into account the views of interested parties – including local residents, although, according to the White Paper, the burden of proof of potential nuisance or disorder would lie with the objector. Mr O’Brien goes on to outline a number of considerations which should “help the licensing authority to develop a local policy framework, within which individual licensing decisions can be made: a framework which fits with its planning and other responsibilities, and which takes account of the wishes and needs of business, local residents, visitors, the police and other interested parties”

Mr O’Brien thinks “that this approach should give residents’ associations and civic and amenity groups some reassurance that local authorities will frame licensing policies which look after their interests”. If such a policy were comparable to planning policies, the fears of many of those with misgivings about the proposed licensing changes might be allayed, but the minister goes on to indicate that the system as laid out in the White Paper remains in his mind: “I do, however, need to make the point that these policies also need to have some flexibility, and that licensing authorities will need to consider all licence applications on their individual merits. The policies should be an aid to consideration, not a substitute for consideration.” In other words, there will be no such thing as a licensing “policy”, in the strict sense of the word as used in local government, merely a set of guidelines, and any suspicion that the same criteria are being applied to all applications will be grounds for a presumably successful appeal. Local government officers and elected members will be anxious to see this issue clarified.

Glen Suarez spoke for Soho residents: “We who live in this environment have had to put up with levels of noise and disturbance, crime and disorder that are extreme. A large majority of people have problems sleeping at night because of noise resulting directly and indirectly from licensed premises. There has been a significant increase in crime, disorder and loutish behaviour particularly after 1.30am. There has been a significant increase in the amount of waste and rubbish in the streets including a significant increase in the numbers of people urinating, defecating and vomiting in the streets. As entertainment premises have increased their numbers and their hours of operation, rental values have risen and many operators running traditional restaurant formats are being forced to compete turning their restaurants into bars, extending hours and increasing the problems we are experiencing.

Let me illustrate what this means in practice: my family now uses ear plugs at night and on most mornings I have to mop the pools of urine that collect in my hall because people use my front door as a urinal. Three weeks ago, my six year old niece picked up a used syringe in the area below my front basement. In the last twelve months there have been six stabbing and knifings outside my house between 1.30 and 4.00am by drunken louts fighting. And I live in the West End in what is considered to be the heart of London.

I see licensing controls as part of a wider set of powers for the public authorities to deal with this kind of situation. I do not see licensing as operating in isolation but it is central to controlling the way in which licensees operate and the environment in which we live.”

Mr Suarez felt that the White Paper proposals were not likely to be helpful. “I do not like the fact that the White Paper is proposing that there should be a burden on objectors who wish to oppose a licence. That is unjust in areas where there are known to be problems such as in the city centres. It will create as unequal contest between applicants and objectors. I believe that this proposal should be abandoned and that licensing authorities should be allowed to have policies that determine whether there should be a presumption in favour or against applications depending on local conditions. Nor do I like the notification procedures proposed or the way in which appeals are likely to be done. In my view not enough emphasis has been given to the importance of crime and disorder as licensing issues and the effect that a concentration of licensed premises can have on an area. These are critical issues.”

Although local authorities in London have taken the lead in attacking the licensing proposals, the rest of the country is equally concerned. Speaking at the same conference, Roger Mortimer from Bristol had this to say: “From 1997 the [Bristol] Police have been objecting to additional on-licensed floor space, as have residents. Licensing Justices have accepted the arguments and refused further on-licenses.

To the noise problems must be added obstruction of entrances, litter, vomit and urine on streets and in gardens and doorways. There is also vandalism to cars and property – and of course aggressive and obstructive behaviour on pavements, with periodic brawling and fighting.

Dislike and indeed fear of all this means that many residents – including some younger ones and students – are reluctant to go out into the environment that now prevails…

The problems may start with drinking inside licensed premises but the consequences are mostly heard, seen, and felt outside in the public realm. Authorities do attempt, with limited effect, to control noise breakout from premises but the real problem is on the streets where it is impossible to pin blame on individual licensees.

Against this background we view the White Paper with considerable alarm. Some rationalization of licensing may be needed. However the welcome given to it by the drinks industry is surely because they expect to sell more drinks.”

It is clear that, when the Government moves to translate its licensing proposals into law, it will meet with considerable opposition. The perception that they are fatally flawed in favour of the licensing trade to the detriment of the interest of local residents is an issue which ministers will not be able to duck.

Let me run this up the flagpole

a personal view of the Portman Group’s new campaign by Andrew Varley

The Portman Group has launched an advertising campaign aimed at discouraging excessive drinking among 18-24 year olds. It is called “If you do do drink, don’t do drunk”, the sort of patronising middle-aged attempt at being hip which makes young people cringe. It has spent a reported £1 million of its members’ money on the exercise – a considerable sum in the general run of things but loose change to the Group’s paymasters in the major drink companies.

Any reader of Alert will be aware of the problems arising from abusive drinking among the targeted age group and it does not take a great deal of imagination to see that more than a few advertisements are needed to deal with them. Does that sound churlish? Surely some acknowledgement should be made to the effort the industry is making to minimise the damage which its product can cause to individuals and the financial burden is imposes on society as a whole – an estimated £3 billion to the NHS alone? Well, up to a point, Lord Copper.

A number of factors need to be taken into consideration. The first of these is the purpose of the Portman Group itself. Ostensibly it is “to reduce the misuse of alcohol by the minority through a strategy of working with other organisations locally and nationally”. The very mission statement, by stressing the word ‘minority’, fosters the comfortable attitude that it is really someone else’s problem.

The Portman Group is billed as the means by which the alcohol industry regulates itself but here there will always be a contradiction. If it ever succeeded in reducing the “misuse of alcohol by the minority”, even to within the so-called sensible limits, then it would bring about a disastrous fall in the profits of its members – Allied Domecq, Bacardi-Martini, Bulmers, Campbell Distillers Pernod-Ricard, Diageo, Interbrew UK, Scottish and Newcastle, and Seagram. No board of directors is going to tolerate this beyond the bare minimum necessary to show willing: to make a gesture, in other words: to avoid “going down Tobacco Road”, as the first director of the Portman Group, John Rae, put it. The Portman Group is a beard. Its purpose is to satisfy a perceived demand for responsibility on the part of the industry without actually harming sales in any significant way.

Does the present advertising campaign confirm anyone in the belief that the industry is serious about the subject of abusive drinking among the young? After all, it is not long since some of its most senior figures were frightened that the popularity of the “rave culture” would produce a generation of non-drinkers. The response was to market drinks aimed precisely at the younger end of the market and which emphasised the psychoactive effects of the drug alcohol and so, by implication, blurred the line between their products and illicit substances.

“Marketing Alcohol to Young People”, recently published by Eurocare and the subject of widespread interest and concern in the media (see page 5), demonstrates how the industry gears so much of its advertising towards the young, which naturally includes those below the legal age limit.

Do you believe in the sincerity of this campaign? Gisela Stuart does, and she is a junior health minister: “This new campaign’s message is an important one.” Dr Liam Fox, the Shadow Secretary of State for Health, says that he wholeheartedly endorses “the Portman Group’s hard-hitting campaign”. Nick Harvey, a Liberal Democrat MP, thinks that the campaign “could not have arrived at a better time.”

These are all professional politicians, of course, and are constantly required to express opinions on a vast range of subjects which are of necessity superficial. It is harder to dismiss the views of the Assistant Chief Constable of Manchester, the Secretary of the Nursing Council on Alcohol, and the Director of Alcohol Concern.

These are all people working at the sharp end of the problem and know what they are talking about. When they endorse the campaign, their words deserve to be taken seriously. No-one could possibly say that the campaign will cause any damage and, of course, any attempt to minimise the problem of youth binge drinking is welcome. The difficulty is in the underlying purpose of the exercise, the gesture to ward off closer regulation, and in the potential efficacy of the advertisements themselves. Perhaps the distinguished endorsers felt that any adverse comment would be like attacking motherhood and apple-pie.

However, there are those of us without these scruples. It has already been argued that the purpose of the Portman Group is to keep the wolves of regulation away from the door of the brewers. But what about the advertisements themselves? Will these exercises in undergraduate humour have any effect? Showing them to a small group of teenagers elicited smiles, certainly, but there was incredulity at the suggestion that posters like this would in any way affect their intake of alcohol.

Picture the conference in the advertising agency: the copywriters sit round their table discussing ways of speaking to youth – a group to which, no doubt, some of them belong. They search their experience, personal or vicarious, for themes to illustrate the brief they have been given by the Portman Group. The premise must have seemed odd. They, or people indistinguishable from them, have been paid vast sums of money to persuade this same group to drink deeply and widely. Now they are being told to do the opposite with what, in terms of alcohol advertising, is a pittance. They are in the position of a lap dancer who has been asked to put in a word for chastity. The task seems so hopeless that they fall back on the last resort of advertising men: whimsy. The way into a young person’s consciousness, they argue, is through a joke based at several removes on the simple conceit of “Men Behaving Badly”, that vomit, inexpert sex, and futility are intrinsically funny. If Freud was right when he said that jokes are one way into the unconscious and are always indicative of repressed wishes, then someone needs help.

But the essential question is not about effectiveness or puerile, condescending humour but about sincerity. What do we say about an industry which through its agents spends a million pounds on an advertising campaign to counter some of the ill effects of its product on young people when it spends many times more than this on promoting the same products to the same age group? The word hypocrisy springs to mind.

WHO challenges drink industry

“Fifty five thousand young people in this [European] region died from causes related to alcohol use in 1999. That is a shocking and tragic waste,” said WHO Director General Gro Harlem Brundtland. The former Prime Minister of Norway was speaking at the Ministerial Conference on Young People and Alcohol held in Stockholm in February. The Conference was attended by delegations from the health ministries of all the countries of the WHO European Region including the United Kingdom.

Mrs Brundtland firmly targeted the drink industry as one of the guilty parties. Quoting the WHO European Charter on Alcohol she said that ” ‘all children and adolescents have the right to grow up in an environment protected from the negative consequences of alcohol consumption and to the extent possible, from the promotion of alcoholic beverages’. Sadly, this is becoming increasingly difficult.” Mrs Brundtland had no doubt where a substantial part of the blame lay: “Not only are children growing up in an environment where they are bombarded with positive images of alcohol, but our youth are a key target of the marketing practices of the alcohol industry.”

During the conference the findings of the 1999 ESPAD (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs) Report were released. Among other findings this showed that young people in the United Kingdom topped the league for use of alcohol and illicit drugs. The ESPAD survey is in the next article “Young are drunk and high”. Her remarks set the note for debates on all aspects of the subject and which led to the Declaration printed below and which was unanimously agreed by the member countries.

Declaration on Young People and Alcohol (Adopted in Stockholm on 21 February 2001)

The European Charter on Alcohol, adopted by Member States in 1995, sets out the guiding principles and goals for promoting and protecting the health and well-being of all people in the Region. This Declaration aims to protect children and young people from the pressures to drink and reduce the harm done to them directly or indirectly by alcohol. The Declaration reaffirms the five principles of the European Charter on Alcohol.

- All people have the right to a family, community and working life protected from accidents, violence and other negative consequences of alcohol consumption.

- All people have the right to valid impartial information and education, starting early in life, on the consequences of alcohol consumption on health, the family and society.

- All children and adolescents have the right to grow up in an environment protected from the negative consequences of alcohol consumption and, to the extent possible, from the promotion of alcoholic beverages.

- All people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption and members of their families have the right to accessible treatment and care.

- All people who do not wish to consume alcohol, or who cannot do so for health or other reasons, have the right to be safeguarded from pressures to drink and be supported in their non-drinking behaviour.

Rationale

Health and well-being are a fundamental right of every human being. Protecting and promoting the health and well-being of children and young people are central to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and a vital part of WHO’s HEALTH21 policy framework and of UNICEF’s mission. In relation to young people and alcohol, WHO’s European Alcohol Action Plan 2000-2005 identifies the need to provide supportive environments in the home, educational institutions, the workplace and local community, to protect young people from the pressures to drink and to reduce the breadth and depth of alcohol-related harm. Further, a major opportunity for putting youth and alcohol issues on the policy agenda is approaching as governments worldwide prepare for the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children, to be held in September 2001, with UNICEF serving as secretariat.

Youth environments

The globalisation of media and markets is increasingly shaping young people’s perceptions, choices, and behaviours. Many young people today have greater opportunities and more disposable income but are more vulnerable to selling and marketing techniques that have become more aggressive for consumer products and potentially harmful substances such as alcohol. At the same time, the predominance of the free market has eroded existing public health safety nets in many countries and weakened social structures for young people. Rapid social and economic transition, civil conflict, poverty, homelessness and isolation have increased the likelihood of alcohol and drugs playing a major and destructive role in many young people’s lives.

Drinking trends

The main trends in the drinking patterns of young people are greater experimentation with alcohol among children and increases in high-risk drinking patterns such as “binge drinking” and drunkenness, especially among adolescents and young adults, and in the mixing of alcohol with other psychoactive substances (polydrug use). Among young people there are clear links between the use of alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs.

The cost of youth drinking

Young people are more vulnerable to suffering physical, emotional and social harm from their own or other peoples’ drinking. There are strong links between high-risk drinking, violence, unsafe sexual behaviour, traffic and other accidents, permanent disabilities and death. The health, social and economic costs of alcohol-related problems among young people impose a substantial burden on society.

Public health

The health and well-being of many young people today are being seriously threatened by the use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances. From a public health perspective, the message is clear: there is no scientific evidence for a safe limit of alcohol consumption, and particularly not for children and young adolescents, the most vulnerable groups. Many children are also victims of the consequences of drinking by others, especially family members, resulting in family breakdown, economic and emotional poverty, neglect, abuse, violence and lost opportunities. Public health policies concerning alcohol need to be formulated by public health interests, without interference from commercial interests. One source of major concern is the efforts made by the alcohol beverage industry and hospitality sector to commercialise sport and youth culture by extensive promotion and sponsorship.

DECLARATION

By this Declaration, we, participants in the WHO European Ministerial Conference on Young People and Alcohol, call on all Member States, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organisations and other interested parties to advocate for and invest in the health and wellbeing of young people, in order to ensure that they enjoy a good quality of life and a vibrant future in terms of work, leisure, family and community life.

Alcohol policies directed at young people should be part of a broader societal response, since drinking among young people to a large extent reflects the attitudes and practices of the wider adult society. Young people are a resource and can contribute positively to resolving alcohol-related problems.

To complement the broader societal response, as outlined in the European Alcohol Action Plan 2000-2005, it is now necessary to develop specific targets, policy measures and support activities for young people. Member States will, as appropriate in their differing cultures and social, legal and economic environments:

1. Set the following targets that should be achieved by the year 2006:

- reduce substantially the number of young people who start consuming alcohol;

- delay the age of onset of drinking by young people;

- reduce substantially the occurrence and frequency of high-risk drinking among young people, especially adolescents and young adults;

- provide and/or expand meaningful alternatives to alcohol and drug use and increase education and training for those who work with young people;

- increase young people’s involvement in youth health-related policies, especially alcohol-related issues;

- increase education for young people on alcohol;

- minimise the pressures on young people to drink, especially in relation to alcohol promotions, free distributions, advertising, sponsorship and availability, with particular emphasis on special events;

- support actions against the illegal sale of alcohol;

- ensure and/or increase access to health and counselling services, especially for young people with alcohol problems and/or alcohol-dependent parents or family members;

- reduce substantially alcohol-related harm, especially accidents, assaults and violence, and particularly as experienced by young people.

2. Promote a mix of effective alcohol policy measures in four broad areas:

- Provide protection: Strengthen measures to protect children and adolescents from exposure to alcohol promotion and sponsorship. Ensure that manufacturers do not target alcohol products at children and adolescents.

- Control alcohol availability by addressing access, minimum age and economic measures, including pricing, which influence under-age drinking. Provide protection and support for children and adolescents whose parents and family members are alcohol-dependent or who have alcohol-related problems.

- Promote education: Raise awareness of the effects of alcohol, in particular among young people. Develop health promotion programmes that include alcohol issues in settings such as educational institutions, workplaces, youth organisations and local communities. These programmes should enable parents, teachers, peers and youth leaders to help young people learn and practice life skills and address the issues of social pressure and risk management. Furthermore, young people should be empowered to take responsibilities as important members of society.

- Support environments: Create opportunities where alternatives to the drink culture are encouraged and favoured. Develop and encourage the role of the family in promoting the health and well-being of young people. Ensure that schools and, where possible, other educational institutions are alcohol-free environments.

- Reduce harm: Promote a greater understanding of the negative consequences of drinking for the individual, the family and society. Within the drinking environment, ensure training for those responsible for the serving of alcohol and enact/enforce regulations to prohibit the sale of alcohol to minors and intoxicated persons. Enforce drink-driving regulations and penalties. Provide appropriate health and social services for young people who experience problems as a result of other people’s or their own drinking.

3. Establish a broad process to implement the strategies and achieve the targets:

- Build political commitment by developing comprehensive countrywide plans and strategies with young people, with targets to reduce drinking and related harm, particularly in the different segments of the youth population, and evaluate (with young people) progress towards them.

- Develop partnerships with young people especially, through appropriate local networks. Look to young people as a resource and promote opportunities for young people to participate in shaping the decisions that affect their lives. Special emphasis should be placed on reducing inequalities, particularly in health.

- Develop a comprehensive approach to addressing the social and health problems experienced by young people in connection with alcohol, tobacco, drugs and other related issues. Promote an intersectoral approach at national and local level, to ensure a sustainable and more effective policy. When promoting the health and well-being of young people, take into consideration their varying social and cultural backgrounds, and particularly those of groups with special needs.

- Strengthen international cooperation among Member States. Many of the policy measures need to be reinforced at the international level, if they are to be fully effective. WHO will provide leadership by establishing appropriate partnerships and utilising its collaborative networks across the European Region. In this regard, cooperation with the European Commission is of particular relevance.

Young are drunk and high

Teenagers in the United Kingdom are among the heaviest drinkers, smokers and drug-takers in Europe. These findings have just been published in the 1999 ESPAD (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs) Report.

According to the survey: “A vast majority of the students in Britain have been drinking alcohol during the last 12 monthsThe proportion reporting drunkenness during the same period is higher than average. Use of marijuana or hashish is reported by substantially larger proportions than average and so is the proportion reporting use of other illicit drugs.”

Below: use of any alcoholic beverage 20 times or more during the last 12 months. Percentage among all students. 1999.

At a time when the topic of methods of marketing alcohol to young people by the industry is coming to the forefront of public debate, it is significant that UK teenagers are the highest consumers of alcopops in Europe. Although “less than half of the students had any spirits on the last drinking occasion”, in the UK and Ireland the large majority of these were girls. On the other hand, if every beverage is taken into consideration, boys appear to drink about 50 per cent more than girls in the ESPAD countries. The largest proportions of teenagers reporting beer consumption were in the Nordic countries, the UK, and Ireland.

Dr Martin Plant, the director of the Alcohol Research Centre, who carried out the British survey, believes that parents should accept more responsibility. At the launch of the report in the Royal College of Physicians, he said that there “is an important issue here, not as to what schools and policy makers should be doing, but a question of parental responsibility.

“If boys and girls live in a family where alcohol, drugs or smoking are taking place then they are going to regard that as normal.” In addition, research comparing France and the United Kingdom showed a link between parental knowledge of a teenager’s whereabouts on a Saturday night and illegal use of alcohol, other drugs, and tobacco.

More than a third of 15 and 16-year-olds interviewed, 36 per cent, had tried drugs, including cannabis and ecstasy.

According to the ESPAD Report, young people in the United Kingdom, whilst having highest levels of alcohol consumption and drunkenness, were also the most likely to have taken illegal drugs. The survey further reported that 20 per cent of British children smoked daily at the age of 13 or younger – the worst figure in Europe.

The report was not, however, entirely bad news for the United Kingdom, as it showed that there had been a slight fall in hard drug use since 1995, the year the last survey was conducted. Illicit drug-taking is estimated to kill 1,200 people a year in the UK, whereas alcohol is thought to be responsible for 35,000 premature deaths. Smoking accounts for something in the region of 120,000 deaths per year.

These figures were quoted by Dr Plant at the launch of the ESPAD survey.

Paul Boateng, the minister for children and young people, said that the Government had started tackling the problem with “a 10-year strategy”. He said: “It is a matter of continuing concern that some young people continue to abuse alcohol and drugs.

“Across government, we are putting in place measures to help, but this cannot just be a matter for government. Encouraging more responsible behaviour among the young is a matter for us all – parents, teachers, friends and communities.”

Mr Boateng made these comments in an atmosphere of mounting concern at the continued failure of the government to produce an alcohol strategy.

Alcohol – Can the NHS afford it?

A report from the Royal College of Physicians shows that alcohol misuse places a huge burden on the National Health Service, costing up to 12 per cent of the total expenditure on hospitals, £3 billion every year. In addition, one in five patients admitted to hospital for other reasons are consuming alcohol at levels potentially hazardous to their health.

The report says: “General Household Survey data from 1998 showed that more than one in three men and one in five women in the UK regularly consume more alcohol than the currently recommended sensible limits. Since this misuse of alcohol can lead to a wide range of physical and psycho-social harm it is not surprising that it places a significant burden on the workload of the NHS – both primary care and hospital services.”

The Royal College stresses the point that the effects of alcohol are complex and can often lie behind other presenting causes for patients’ use of hospital services: “Alcohol misuse is a major cause of attendance and admission to general hospitals in both the A&E/trauma and non-emergency setting. It may cause admission directly, or together with other causes contribute to admission. Alcohol may also increase the burden on hospital services by adversely affecting the course of illness following admission.”

It is important to note that the burden of alcohol misuse on the workload of general hospitals results from damage not only to the misuser himself, but also to other people affected by the excessive drinking such as friends and relatives and those involved in accidents caused by intoxicated drivers.

Because of the huge size of the burden placed by alcohol on hospital services and the consequent financial implications, the writers of the report urge that appropriate strategies be put in place for the early identification and management of harmful and hazardous drinkers. “For effective early detection, detailed alcohol histories must be sought from patients who present with conditions often associated with alcohol misuse. However, considering the high frequency of hazardous drinking in all patients presenting to hospital services, a strong case can be made for incorporating screening for alcohol misuse into the routine health care provided in the general hospital setting.”

The RCP is particularly concerned about teenage alcohol consumption. This age-group appears to be drinking larger amounts of alcohol – in 1998, over half of 14-15 year-olds had drunk alcohol in the past week. Younger teenagers are also drinking more, and research shows that heavy drinking teenagers are more likely to continue their habit as young adults. This indicates that alcohol is not only a huge problem for the NHS now, but will be increasingly so in the future unless prompt action is taken. Professor Ian Gilmore, Registrar of the Royal College of Physicians and Chairman of the working party, said:

“Alcohol is an issue which needs to be tackled on all fronts, especially by changing attitudes to alcohol-related problems across the NHS. If we start at the sharp end of hospital admissions with detection and simple interventions for patients who are starting to drink dangerously, there is good evidence that we can make a real difference.”

This authoritative report’s recommendations are intended to improve the management of the vast number of patients presenting to general hospitals in the UK who drink alcohol in excess of sensible limits. Their main points are:

- The creation of a National Alcohol Director to give the issue a higher profile

- Early publication and implementation of a National Alcohol Strategy

- Every acute NHS hospital Trust to have a defined hospital strategy to identify, assess, refer, treat and follow-up problem drinkers

- Better education on alcohol for doctors, nurses, medical students and other health workers.

Adolescent alcohol consumption: the drug link

The evidence is clear that in teenagers and young adults, drinking – especially heavy drinking – is often linked to smoking and the use of illegal drugs. But how should this link be understood? Do drinking and drug taking just happen to co-exist, or does the one cause the other. Here Jeremy S Gluck, Research Director of Adolescent Assessment Services (AAS), analyses the results of an AAS survey to throw light on these questions.

Causal links between one form of behaviour and another are always hard to establish. Normally this is due to myriads of additional overlapping factors or confounding variables. However, the link between adolescent alcohol use and other substance use appears clear: research has shown that there is little illegal drug use without preceding or concurrent alcohol use (i.e. Sutherland and Willner, 1998).

In this article I will present data gathered during 1999 and 2000 from 32,652 11-16 year olds from all over the UK. These data were collected by Adolescent Assessment Services (AAS), an independent research organisation working closely with Local Education Authorities and Health Departments to establish levels of and reasons behind substance use in young people. Firstly, current drinking, smoking and drug use levels will be presented and these behaviours will then be linked.

Alcohol Use

Using a specifically designed self-report questionnaire, AAS asked children about their drinking habits and found that 16.6 % of 11-16 year olds claimed to drink alcohol on at least a weekly basis. Table 1 shows these data by age and gender. Of those children who claimed any alcohol use at all, 38.5 % said they only drank yearly, 34.2 % said they drank monthly, 20.6 % claimed weekly use, 4.9 % said they drank on at least two to three occasions a week and 1.8 % said they drank daily.

|

Table 1 – Weekly or greater alcohol use by age and gender

|

||||||

| Age |

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

| Males |

7.2

|

9.9

|

16.1

|

23.4

|

35.9

|

47.8

|

| Females |

6.8

|

3.5

|

13.8

|

19.0

|

31.9

|

34.3

|

| Mean |

5.3%

|

8.3%

|

14.9%

|

21.1%

|

33.8%

|

40.8%

|

Children were also asked about incidents of drunkenness in the year preceding the survey. Out of all the children surveyed, 40.6 % claimed to have been drunk on at least one occasion. Details of occurrences of drunkenness by this sub-group of children can be found in Table 2.

|

Table 2 – Incidents of drunkenness (all figures are percentages of children claiming to have been drunk)

|

||||||

| Age |

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

| 1-2 times |

61.3

|

57.9

|

49.8

|

41.3

|

36.8

|

36.5

|

| 3-5 times |

20.7

|

17.9

|

24.3

|

26.6

|

23.0

|

22.0

|

| 6-10 times |

6.8

|

10.9

|

11.4

|

12.3

|

14.4

|

15.0

|

|

11-20 times

|

4.3

|

4.8

|

6.5

|

8.9

|

9.6

|

8.8

|

|

20+ times

|

6.8

|

8.5

|

8.0

|

10.9

|

16.2

|

17.8

|

Children were also asked about their illegal drug use and 3.3 % claimed to use drugs at least weekly. Drug use by age and gender can be found in Table 3. Typically, more boys than girls claim illegal drug use.

Drug Use

|

Table 3 – Weekly or greater drug use by age and gender

|

||||||

| Age |

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

| Males |

1.2

|

1.9

|

2.7

|

5.9

|

8.4

|

8.8

|

| Females |

0.5

|

0.9

|

2.4

|

4.5

|

6.9

|

6.6

|

| Mean |

0.8%

|

1.4%

|

2.5%

|

5.2%

|

7.6%

|

7.7%

|

Respondents were also asked about their regular smoking habits which were defined as any smoking which took place on a daily basis. The percentage of children smoking regularly can be found in Table 4. In line with other research of this type, it was found that considerably more girls than boys claimed to smoke.

Cigarette Smoking

|

Table 4 – Proportions of children reporting daily smoking

|

||||||

| Age |

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

| Males |

4.7

|

6.3

|

9.5

|

14.7

|

18.0

|

20.9

|

| Females |

4.8

|

6.2

|

15.1

|

20.5

|

29.1

|

28.2

|

| Mean |

4.8%

|

6.3%

|

12.4%

|

17.7%

|

23.9%

|

24.7%

|

Alcohol and Drugs

AAS then looked at the relationship between alcohol and drugs and, as in the earlier study by Sutherland and Willner, found that a close relationship exists between use of alcohol and use of illegal drugs. The basic fact which emerged from the analyses was that 1.3 % of non-drinkers said they used drugs compared to 14.1 % of drinkers. However, the relationship went deeper than this and we found that the more often a child drank the more likely they were to use illegal drugs. Table 5 shows this relationship in detail.

|

Table 5 – Occasions of alcohol drinking and drug use

Occasions of Drinking |

|||||

|

Yearly

|

Monthly

|

Weekly

|

Weekly +

|

Daily

|

|

| Males |

1.5

|

2.6

|

11.7

|

15.5

|

31.8

|

| Females |

0.3

|

2.9

|

11.9

|

21.5

|

29.3

|

| Mean |

0.9%

|

2.7%

|

11.8%

|

18.2%

|

31.0%

|

A similar relationship was found between drunkenness and drug use. 0.7 % of children who said they had never been drunk in the preceding year claimed drug use compared with 7.3 % of children who said they had been drunk on at least one occasion. As with incidents of drinking, the more often an adolescent had been drunk, the more likely it was that they would also claim drug use. Table 6 shows this relationship in detail.

|

Table 6 – Occasions of drunkenness and drug use Occasions of Drunkenness

|

|||||

|

Yearly

|

Monthly

|

Weekly

|

Weekly +

|

Daily

|

|

| Males |

3.3

|

5.8

|

8.2

|

13.3

|

25.3

|

| Females |

2.8

|

5.2

|

8.1

|

11.7

|

25.3

|

| Mean |

3.0%

|

5.5%

|

8.2%

|

12.5%

|

25.3%

|

It is interesting to note that, unlike simple use which is mediated by age whereby substance use increases with age, no such effect was noted here. For instance, 14 % of 12 year olds who drank said they used drugs compared with 12.3 % of 16 year old drinkers.

Alcohol and Smoking

Finally, we looked at the relationship between adolescent drinking and smoking and the strength of the association between drinking and smoking was startling. 7.6 % of non-drinkers smoked compared with 39.8 % of regular drinkers. Table 7 shows that the more often a child drinks the more likely it is that they will be a smoker too. In particular it is notable that 65 % of girls who claimed to drink on a daily basis also claimed to smoke. As with the relationship between alcohol and drugs, no age effect was noted. Although, as we have seen, smoking increases with age, when alcohol was factored in, smoking was stable across the age range (33.9 % of 11 year old drinkers smoked compared with 34.2 % of 16 year old drinkers).

|

Table 7 – Occasions of alcohol drinking and smoking

Occasions of Drinking |

|||||

|

Yearly

|

Monthly

|

Weekly

|

Weekly +

|

Daily

|

|

| Males |

5.4

|

12.0

|

27.0

|

33.2

|

49.4

|

| Females |

6.6

|

22.2

|

47.5

|

63.7

|

65.0

|

| Mean |

6.0%

|

17.2%

|

36.9%

|

47.0%

|

54.3%

|

Of those children who said they had never been drunk 3.8 % said they were smokers, this compared to 26 % of children who said they had been drunk on at least one occasion in the year before the survey was carried out. As with the data reported earlier, it can also be seen in Table 8 that a clear relationship exists between occurrences of drunkenness and smoking: The more often a child is drunk, the higher the incidence in smoking. Again, this is particularly so in girls.

|

Table 8 – Occasions of drunkenness and smoking

Occasions of Drunkenness |

|||||

|

Yearly

|

Monthly

|

Weekly

|

Weekly +

|

Daily

|

|

| Males |

11.1

|

15.9

|

26.3

|

31.6

|

44.1

|

| Females |

19.4

|

31.7

|

45.1

|

55.9

|

62.6

|

| Mean |

15.2%

|

23.9%

|

36.0%

|

43.2%

|

52.7%

|

Discussion

It can be seen from these data that there is a strong association between alcohol, adolescent smoking and illegal drug use. However, I am not suggesting that alcohol drinking necessarily causes drug use. These data simply report on an association between the variables and it would not be scientifically or statistically correct to assume causality from this type of information. This is particularly the case as the information only relates to three specific variables whereas we know that dozens of others exist and act on individuals and that these variables will all play their part in all their substance using habits. Having said that, the association between alcohol and other substance use is extremely robust and too strong to discount. If the caveat of association rather than causality is accepted why is this association so pronounced?

Firstly, we live in a culture of substance use and use of alcohol in particular is normal in our society. Well over 90 % of adults drink alcohol on a regular basis and this use is reflected in increased drinking by our children. All the time children are bombarded with images of adults drinking alcohol either in the media or in their own homes, therefore the idea of ingesting a foreign substance is not alien to them. Children who are used to drinking are therefore less likely to refuse if offered a different drug simply because it is not unusual for them to be in the presence of consistent psychotropic drug (alcohol) use.

However, the fact that we have found almost no drug use without preceding alcohol use is indicative that there is ground for serious concern as regards adolescent alcohol abuse leading to drug use. Another reason for the association between alcohol and drug use is the disinhibiting effect of alcohol. Imagine a child who has drunk to excess: Is that child more or less likely to accept, say, any Ecstasy tablet than a sober child? The answer appears clear.

AAS asserts that this is a more complex and intractable problem that might at first be realised, and that currently the approaches to dealing with adolescent substance abuse are, at best, only marginally successful. The danger in underestimating the gravity of the situation is that the temptation to ascribe such trends purely to recognised, accepted factors can result in a perception of the problem that obscures the more deep-lying social causes.

Our data therefore suggests that if you can reduce adolescent alcohol use, you can subsequently reduce other types of adolescent substance use. In addition, it is reasonable to conclude that as the use of alcohol can lead to less inhibited behaviour other behaviours such as premature and risky sexual behaviour may be reduced if adolescent alcohol use is decreased. On this latter point, and in light of the fact that one person is diagnosed as having the HIV virus in the UK every three hours, it is clear that the benefits of reduced adolescent alcohol use could have important results.

The complacency about the centrality to our society of routine alcohol use, and the general reluctance to really address the causal links between adolescent alcohol use and adolescent drug use and sexual behaviour, shows that data such as we have collected is of great concern.

Until and unless we can honestly address the causal factors and link between alcohol and drug use, especially in children, we cannot expect to see a significant reduction in usage figures. Perhaps one reason that the causal link is not properly conveyed is that, simply, the distinction made to adolescents between alcohol and drugs is too facile. Alcohol use, for all its evident perils, is made to seem fundamentally inevitable and acceptable as of legal age, from which a young adolescent might well infer that drinking under legal age is more a matter of inclination than anything more.

Drugs, on the other hand, are presented as fundamentally unacceptable, and their criminal status emphasised. Therefore, the causal link between alcohol and drugs is obscured and even broken by making alcohol a conditional positive, but drugs an unconditional negative. This breaking of the causal link in educating adolescents in the hazards of abuse has its own hazards, including the fact that unless the gravity of alcohol abuse is conveyed as being unconditionally equal to that of drug use, young people might infer that alcohol use has little connection to drug use; this disassociation could certainly lead to a “comfort zone” around alcohol use where it is felt that drug use is rather divorced from the former, and therefore that alcohol use and abuse is less consequential.

It is important to note at this point that it is not the assertion of AAS that alcohol has in any way to be criminalised to deter its abuse by adolescents, but rather that education in substance use must reflect current research and clearly present the links established by work such as this.

AAS is endeavouring to broaden and deepen the scope and methodology of its research and provision of data to public and private bodies concerned with public health in order that this problem, which represents a critical dilemma for our society, can better be dealt with and ameliorated at the causal level. Therefore, in addition to baseline information, AAS is now in the process of gathering data related to the causes of alcohol and other substance abuse including information on expectations, attitudes, social correlates and personality variables.

Once the causal link between alcohol and drug use in adolescents can be formally established, more incisive education about it can begin, with potential reduction in present levels being a real possibility.

Can we afford any longer to obscure the link between alcohol and other types of drug abuse by children?

References

Sutherland, I & Willner, P. (1998) Patterns of substance use among English adolescents, Addiction, 93, 8, 1199 – 1208.

Launch of a Nursing Council on Alcohol

Three-hundred UK nurses attended the Nursing Council on Alcohol launch conference where national and international nurse leaders emphasised the importance of the identification of harmful alcohol use, and why nurses should be offering brief interventions to patients drinking at harmful levels.

Deputies representing the Chief Nursing Officers (CNO’s) for Scotland, England and Northern Ireland attended. Video messages of support were relayed from Sarah Mullally, CNO England, and Professor Oliver D’A Slevin, Chairman of the National Board Northern Ireland along with written messages from The Baroness Flather JP DL, Chairman of AERC and Ms Anne Jarvie CNO, Scotland. The Prime Minister faxed a message offering support, and encouraging the initiative:

“I would like to take this opportunity to welcome the establishment of the Nursing Council on AlcoholNurses have a crucial role to play in promoting sensible drinking and your organisation will help to ensure they make the fullest possible contribution to this goal”

What will the Council Do

The Nursing Council on Alcohol will:

- Establish a network of individuals with particular knowledge of, and interest in alcohol problems that can contribute to the work of the council within their spheres of expertise.

- Arrange symposia, education, and training programmes for dissemination of information about prevention, treatment and after care of the individual drinking harmfully.

- Publish regular Newsletters, sponsor and commission the publication of journals, books and papers relating to problem drinking.

- Develop and maintain a web site.

- Develop and maintain a library/resource facility.

- Initiate, co-ordinate and give advice and guidance on research projects.

- Stimulate nursing education and training on the subject of problem drinking, its prevention, treatment and after-care.

- Act as a consultative body for organisations and individuals on the nursing aspects of alcohol related health problems.

- Develop affiliation and joint working relationships with appropriate organisations.

- Take our membership of organisation, and support initiatives from other organisations, whose activities and interests are compatible with the aims of the Council.

- Consult the membership.

- Seek discounts and favourable terms for conferences and publications for members.

The Councils steering committee is directing its energies towards raising awareness, and providing advice and information, to the nursing profession. The theory is that raised awareness of harmful alcohol use will lead to the early identification and the consequential provision of adequate and appropriate intervention at the entrance point to nursing care.

The Council aims to register as a charity with an elected management committee.

The management committee, formed from an equal number of elected representatives from Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland, will be responsible for taking forward the aims and objectives of the council within their own country. Eventually, a network of local and regional advisors will be introduced.

The Glasgow Caledonian University based head office will eventually house the management committee and subcommittee(s). This will be a centre of excellence offering information and guidance to anyone. AGM’s will move round the country. A structure will be introduced to allow for an open approach to communication and dispersal of information in a free and continuous, unobstructed flow, jargon free and easily accessible leading to a transparent body and building membership trust and participation.

Whilst the Councils primary function is nursing related, membership will be open to all registered nurses, students, corporate services; and associate membership being available to other professions.

Current Activities

Since the November 2000 launch, the Councils has been overwhelmed with offers of support and encouragement, as well as, requests for information, advice, education and writing, a briefing request from a Scottish MP, and a consultation document from the Scottish Health Executive. England, Northern Ireland and Wales have received similar information and guidance request.

The constitution is currently under preparation and will be circulated to members. Once final membership approval is gained application for charity status to commence and steps taken to bring about the Councils first democratic, membership elected management committee.

The Council and Alcohol Concern are working together to develop guidelines for practice nurses, in relation to the identification of harmful alcohol use. The guidelines will go out for consultation in July 2001, and be published in time for Alcohol Concerns AGM in October, and the Councils November conference.

The Council in partnership with Alcohol Concern have launched a nurses Internet bulletin board. The board is on Alcohol Concerns Web Site: www.alcoholconcern.org.uk In addition, negotiations are ongoing to gain a journal subscription discount, for The Drug and Alcohol Professional, a new practitioner journal for Council members.

How you can help the Council

- Become a member of the Nursing Council on Alcohol. When you join the Council, you support and fund the organisations work.

- Organise local promotional events. The Council can provide speakers to address event, or to talk to organisation you identify.

- Promote the work of the Council via local media. The Council can provide appropriate support and or material.

- Raise nurse awareness within your region or local area. The Council would like to hear from about piloting your initiative and sharing this with others through a poster presentation at the November 2001 conference.

- Do you know of an individual or organisation willing to offer financial support or sponsorship? If we are to take this initiative forward, we need to locate and secure short and long-term funding.

- Help build up the resource centre. If you have any publications, information or other resources that you would like to donate, and or you have contact with an individual or organisation that would like to make a donation, or offer equipment and office furniture, please contact the Councils Secretary.

| Membership of the Nursing Council on Alcohol

To find out more about the Council contact: Dr Hazel Watson Tel: (+44) (0) 141 331 3457 Fax: (+44) (0) 141 331 8312 |

Alcohol and London’s youth

At a recent seminar on Alcohol and the Family arranged jointly by the NSPCC and ARP (Alcohol Recovery Project), Trevor Phillips, the Chairman of The London Assembly and a well-known broadcaster and journalist, spoke about his view of the problem alcohol posed for young people in the capital and his vision for helping them avoid the pitfalls:

At the Greater London Authority, we intend to adopt a proactive role for we understand that [child welfare] is a major issue for everyone living in London. The GLA has a duty to promote the health of Londoners. Tackling alcohol and drug use can lead to substantial improvements in health. As a member of the London Health Commission I intend to ensure that your work with Alcohol and Families informs our health strategy.

London is a diverse and complex city and the use of alcohol is a significant feature of London life. London is the centre of Britain’s music and dance scene, and has a thriving nightlife. For the majority, drinking a glass of wine or a few beers is an unremarkable part of their social life during the evening and at weekends.

However London is a young city with a higher proportion of children under the age of five than the rest of the country and where more than 20 per cent of the London population – one and three quarter millions – are under the age of 18. By 2011 one in three Londoners will be under the age of 25.

Children and young adults are at the very heart of this city. They need freedom to have fun and to discover their limits; but they also need protection and support to ensure that their experiments and exploration don’t end up in disaster. Far too often we get the balance wrong, and instead of benefiting from the potential of living in this great city they are destroyed by alcohol or drug misuse, or the behaviour of the very adults who are supposed to be caring for them.

We all have some knowledge of the problems which confront those who are addicted to alcohol. A few of us may have been consciously touched by the disruptive impact alcoholism can have on the lives of families, friends, neighbours, and workmates.

However, most of us take the rather comforting view that alcoholism and alcohol misuse is a problem for a small minority of the population made up of people we don’t know, who do not live as we do, and who we are unlikely ever to meet.

The truth is that increasingly alcohol misuse is every community’s problem, perhaps even every family’s problem.

Approximately one million children in the UK are living within families where there are alcohol problems. In a recent study of child protection in two London boroughs, heavy alcohol use was reported in 50 per cent of families with children on the child protection register. Alcohol plays a part in 70 per cent of all stabbings and beatings.

When things go wrong in families children are deeply affected. When I talk to young people today and ask them what is the most important thing in their lives, most of them say that it is family and friends. The family, whatever its shape, is still the most important source of support for most young people. In families where there is alcohol misuse this support is often jeopardised

If we want to understand the needs of these young people we have to listen to them. This is exactly what we have been doing at the GLA at a recent consultation which they called ‘Sort it Out’. We consulted 2500 children, mostly 9-13 year olds, and as with most youngsters they were very forthright in their opinions. In a discussion on alcohol and drugs they said they are:

- Extremely frightened in the presence of drunk adults whether these are people they know or strangers and

- They believe that drunken behaviour leads to violence and they are very concerned about the number of drunken people they encounter on the streets.

- They worry about their own safety.

They are right to be worried. The figures of alcohol induced violence show that show 60 -70 per cent of men who assault their partners do so under the influence of alcohol. The fact is that these children’s fears reflect, if not their own experiences, those of a classmate or friend.

That is why the initiative proposed by the NSPCC and ARP is so vital in offering support to families.

However, parents and adults may not be the only people who misuses alcohol in a household. We know that, however closely a parent may supervise their children, we cannot control their actions every minute of the day. A further issue, which should be a concern for us, is the increased level of alcohol misuse among young people in the UK

I am sure that many of you are aware of the findings of the recent World Health Organisation study on ‘Alcohol and Drugs use among Teenagers in Europe’. The signals here are unmistakable and we cannot afford to ignore them.

The study found that drinking among teenagers in the UK is on the increase. It concludes that British teenagers take more hard drugs, get drunk more often and start smoking earlier than most of their European counterparts. Britain has the highest level of binge drinking and drunkeness in Europe. 1 in 8 deaths among young men 15-29 year olds is alcohol related. This is a figure that is nearly double what it was a decade ago.

And the drinking is starting earlier. 29 per cent of 15-16 year olds here have been drunk more than 20 times in their lifetime – only the Danes are worse. 40 per cent of our boys have been drunk before they were 13, and most them claimed to have been drunk more than 20 times by that age. The figures are simply appaling.

To make matters worse, there is evidence that excess use of alcohol and use of illegal drugs go together. Alcohol and drug misuse seriously threatens the health and well being of many young people in the UK. In London the use of alcohol and other drugs are strongly linked. Alcohol, drug dealing and drug use often occur in the same environments-whether in pubs, clubs and or on the street.

Alcohol misuse in children is a predictor of drug and other problems in later life.

Nearly one in ten young Londoners aged between 16 and 29 years old used cocaine in the last year and nearly one in five women and two in five men between the ages 15 and 24 years old report regularly drinking twice the recommended daily limits.

The challenge which confronts us is to discover ways of encouraging young people to use drink sensibly, now that drinking and drugs are such an integral part of youth culture.

First we need to recognise that the recourse to excessive drinking and drugs has not come about by accident. We can’t blame everything on public policy but there are aspects of what Government and local authorities have done which have not helped. The years of youth club closures, the decimation in London of the Youth Service, the loss of sporting facilities mean that today, many young people have no access to after-school activities, little access to adequate sport facilities and youth services.

But what they do have is easy access to alcohol on the streets. Many are bored with nothing to do and nowhere to go – alcohol provides them with an escape route.

Problem drinking among young people can raise the risk of suicides, criminal behaviour, teenage pregnancy/unsafe sex, and school exclusions The social costs are also significant, alcohol misuse costs industry an estimated £2 billion per year, and alcohol related crime costs the government around £50 million a year.

Even if and when we do remedy that situation we face a much bigger, much more alarming cultural problem. Put bluntly, both our media and our public figures have lost the plot on this issue, and are creating a kind of mayhem of which they are barely aware.

Last night I watched the celebrities on the latest Big Brother complaining that they were running out of food. It might have been just a case of incompetence; but actually they explained that they had spent their allowance on drink. The message – the way to cope with the stress of living with Vanessa, Chris, and Anthea is to resort to alcohol.

In fact we are now not only celebrating excessive social drinking. We are wallowing in the consequences of misuse. It has now become a commonplace in a star’s life to turn to addiction because of the “stress” of having talent, fame and money. The next phase is the post-drying out interview in which we hear a story of remorse and redemption. Every entry and exit to the Betty Ford Clinic or the Priory is recorded in loving detail and becomes the source of another triumph over tragedy story. That is until the patient returns for another period of “rest”.

We applaud their heroism, forgetting that another young person’s life has been ruined, and that all the people around them have had their lives disrupted.

The well-publicised crises of Daniella Westbrook, Kate Moss, Michael Douglas and others are a signal that addictive behaviour is now just another chapter in the celebrity narrative. The signal says that such a crisis will make you stronger, because that is what we read in the star’s interview. Actually for most kids, it doesn’t make them stronger, it simply destroys their future.

A young person’s first line of defence against insecurities should be the family. If a family is incapable of providing support and protection, or simply isn’t available for one reason or another, it falls to the wider community, particularly the government and voluntary organisations, to help.

If we are to assist young people then tackling alcohol and drug misuse must be at the top of our agenda. We must ensure that there are specialist facilities and services designed to meet their needs and in doing this we must consult with and learn from them. In London we also have a special responsibility to ensure that services provide for the needs of children across the diversity of London’s many communities.

At the GLA we have begun work on an alcohol and drug strategy in partnership with the new London Health Commission. We have recently set up a small Drug and Alcohol taskforce that includes the chair of LHC and myself.

We are taking this issue extremely. The Mayor is committed, as I am, to practical programmes to encourage change. We will shortly be meeting the Government Drug Tsar Keith Hellawell to discuss the issues. At the heart of our approach is harm reduction.

We want to ensure that resources are focused on behaviour that causes the greatest damage to individuals and communities. We want to use the strength of those families and communities to tackle the problems.

The GLA will bring together Local Authorities, the Metropolitan Police, social services, health agencies, voluntary organisations, community representatives, those providing alcohol and drug services to discuss the strategy. Although alcohol and drug use is an issue for the whole of the country a pan-London initiative could be used as a model of good practice for the rest of the country.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Bottling Up Trouble: alcohol, workplaces, and the need for change

Tabbin Almond –

Alcohol-freedom coach and author