In this month’s alert

Alcohol policy – what the public thinks

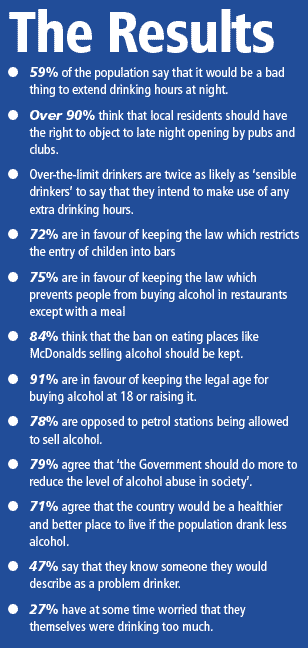

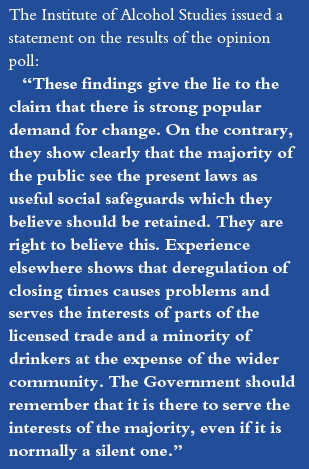

In what will be a shock to Government ministers, the majority of people say that it would be a bad thing to extend pub opening times at night and reject the concept of continental drinking. These are among the results of a national opinion poll recently conducted by NOP* on behalf of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

The Government will have to look again at its plans for the reform of licensing regulation, which are expected to be published as a White Paper in the near future but which were leaked to the Daily Telegraph before Christmas. Ministers have made it clear that they are looking to a wide-ranging liberalisation of the present laws and give the impression that they believe that the majority of the British people agree with them. The dramatic results of this opinion poll will force them to re-examine their presuppositions.

Asked whether it would be a good thing or a bad thing to extend drinking hours at night, 59 per cent said that it would be bad, an eighteen point lead over those who thought it would be good. However, and perhaps unsurprisingly, substantial majorities in both men and women who habitually drink beyond the sensible limits (21 units per week for men, 14 for women) thought extended hours were a good thing. There was some regional variation, with Wales and the West showing a huge majority of over thirty points against longer hours. Only in Scotland, Yorkshire, and London was the difference less than ten points. Among men there was a small majority for the idea of extended hours (8 per cent) and among women a huge majority against (42 per cent).

The 41 per cent who thought it would be a good thing to extend drinking hours at night were asked about the days on which there should be later opening times. 45 per cent (that is, 18 per cent of the whole sample) preferred every night, 7 per cent wanted to see an extension on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, 12 per cent on Thursdays, and 11 per cent on Sundays. Unsurprisingly, Friday was favoured by 45 per cent and Saturday by 47 per cent.

The 41 per cent who thought it would be a good thing to extend drinking hours at night were asked about the days on which there should be later opening times. 45 per cent (that is, 18 per cent of the whole sample) preferred every night, 7 per cent wanted to see an extension on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, 12 per cent on Thursdays, and 11 per cent on Sundays. Unsurprisingly, Friday was favoured by 45 per cent and Saturday by 47 per cent.

All the sample were then asked as to which time they thought closing time should be in residential areas. In this case there was a substantial majority, 64 per cent, in favour of no change. Even among those men who drink beyond the sensible limits, 42 per cent preferred no change to evening hours in residential areas. The picture is a little more complicated when it comes to town and city centre pubs. However, what may surprise ministers is that even there, 44 per cent (33 per cent men and 55 per cent women) would prefer closing time to remain as it is now. A further 12 per cent would want an extension of no more than an hour, giving a total of 56 per cent who prefer town and city centre pubs to be closed down no later than midnight. 27 per cent believed that pubs should be allowed to serve drinks as long as they wanted with no set closing time. Leaving things to the discretion of the landlord, of course, is not necessarily the same thing as wanting pubs to remain open much longer than they do at the moment.

Asked whether, in the case of drinking hours being extended beyond 11 pm, they would take advantage of the later opening hours, 56 per cent said they would not, with a further 11 per cent speculating that they might do so once a year. Only 14 per cent thought they would use the extra drinking time once a week and 7 per cent more than once a week. Within these figures there is a 2 to 1 majority of those who drink beyond the safe limits. It would be ironical if the main beneficiaries of licensing reform turned out to be abusers of alcohol, given that the government is currently preparing its national strategy against alcohol abuse.

In England and Wales there has been some discussion as to where the power to grant licences should lie. The choice is between a continuation of the present system where it is the hands of licensing magistrates or some form of local accountability. The latter could either be a committee of the council or a licensing authority which would consist representatives of local interests, possibly including councillors, magistrates, health authority members, and the like. Whilst most of the questions in the poll had some implication for any community-based approach to licensing, two had specific relevance. Those questioned were asked, “Do you think that people who live in an area should have the right to object to late night opening by pubs and clubs or not?” An overwhelming 92 per cent wanted the right to object. There was no great variation in class, sex, age, or region (except, perhaps, the 18 per cent which separated Scotland on 82 per cent from the north-east on 100 per cent).

Similarly, 90 per cent of the population believe that people should have the right to object if they think that too many pubs and clubs are being opened in the area in which they live. There is even less variation according to class, age, sex, or region for this question.

These very substantial percentages send a strong message to Government that people want to have a greater say in how licences are granted in their own communities.

Ministers past and present have also made the assumption that the British people want to import the continental café into the United Kingdom, removing the restrictions on family use of pubs and making it possible to have a beer or glass of wine in the local fast-food outlet. The results of the opinion poll contradict this notion. People were asked whether they thought that the present law restricting the entry of children under 14 into bars should be kept or that they should be allowed legally into all bars and pubs when accompanied by an adult. 72 per cent believed that the present law should be retained, with very little variation across the categories mentioned. An astonishing 84 per cent said they wanted to retain the present law which bans eating places such as McDonalds selling alcohol. Nor do a sizable majority (75 per cent) of the British public wish to see restaurants allowed to sell alcohol other than with a meal.

Ministers past and present have also made the assumption that the British people want to import the continental café into the United Kingdom, removing the restrictions on family use of pubs and making it possible to have a beer or glass of wine in the local fast-food outlet. The results of the opinion poll contradict this notion. People were asked whether they thought that the present law restricting the entry of children under 14 into bars should be kept or that they should be allowed legally into all bars and pubs when accompanied by an adult. 72 per cent believed that the present law should be retained, with very little variation across the categories mentioned. An astonishing 84 per cent said they wanted to retain the present law which bans eating places such as McDonalds selling alcohol. Nor do a sizable majority (75 per cent) of the British public wish to see restaurants allowed to sell alcohol other than with a meal.

There has been no official suggestion that the liberalisation of the licensing laws proposed by ministers should include any change to the legal age for buying alcohol but some time ago the drink industry did begin to make some moves towards a lowering of that age. The controversy over alcopops put a temporary halt to this. This poll shows that such a move would be deeply unpopular, the vast majority of the population believing that the legal drinking age should be kept as it is, and more people wanting it to be raised than lowered. As far as personal drinking was concerned, 83 per cent of those surveyed drank alcohol at least occasionally, 17 per cent did not drink. 18 per cent of men and 7 per cent of women admitted to drinking above the traditional sensible limits (21 units per week for men, 14 for women). However, 38 per cent of men and 16 per cent of women have at some point in their lives worried that they were drinking too much alcohol. In addition almost half the population (47 per cent) know someone personally they would describe as having an alcohol problem.

(* NOP Solutions carried out the survey over 1800 adults aged 15 years and over using a random location sample. The sample was designed to be representative of all adults in Great Britain. Interviewing took place between 6th and 11th January, 2000.

Community initiatives

In a society where drinking alcohol is part of most people’s social life, it is important to be able to measure both the impact of its misuse and the success of the efforts being made to tackle the problem. Alcohol, after all, is associated with a wide range of health and social problems , including violence, accidents, and chronic illness, which affects not only the individual but the communities where they live.

The Health Education Authority has published a book, Alcohol: measuring the impact of community initiatives,* which draws on research carried out in two communities as well on the experience of a wide range of professionals working to reduce alcohol related harms.

The book provides guidance on setting up the means to assess the impact of any measures taken in a community. At a time when more local authorities are looking to act alongside health authorities in dealing with the problems caused by alcohol as well as illicit drugs, this publication will prove invaluable.

* Alcohol: measuring the impact of community initiatives, Betsy Thom, Moira Kelly, Sarah Harris, and Angela Holling, Health Education Authority.

That Monday morning feeling

Further light on the impact of alcohol is provided by a new study from Scotland which suggests that up to 20 per cent more people die from heart attacks on a Monday than any other day. Weekend boozing and the thought of going back to work may well be contributing to this trend. An article in the British Medical Journal* makes much the same suggestion as to the link between these heart attacks and the stress of returning to work after two day’s socialising. These findings have led to a demand for more research into the connection between excessive drinking and coronary heart disease.

The records of approximately 80,000 Scottish men and women who died of heart disease were investigated and it was discovered that the number of deaths peaked on Mondays. For example, deaths of women under 50 with no previous history of heart disease rose by a fifth. Among men of a similar age who also had no previous heart trouble, there was a 19 per cent increase on Mondays.

On the other hand, the researchers found that the lowest number of heart-related fatalities occurred on a Tuesday. Dr Christine Evans, the report’s author, said that “Monday peak in deaths from coronary heart disease in Scotland may be partly attributable to increased drinking at the weekend, although other mechanisms, such as work-related stress, may be important.

“The possible link between binge drinking and deaths from coronary heart disease has potentially important public health implications and merits further investigation.”

It was noted that people with previous admissions for heart problems had no significantly increased risk of death on Mondays. It is suggested that these people were more likely to recognise warning signs and get to a hospital if necessary. It is also likely that people with a history of heart disease were probably on medication which stabilised their condition.

It is a well established fact, and one attested to by hospital staff throughout the United Kingdom, that weekend over-indulgence also leads to a considerable rise in the number of people appearing in casualty departments the worse for drink – 64 per cent more on an average Saturday night that on weekdays.

*”I don’t like Mondays’ – day of the week of coronary heart disease deaths in Scotland: study of routinely collected data, Dr Christine Evans et al., The British Medical Journal, 22nd Jan 2000, Vol.320.

Minister lays down the law

The Government expects licensees to see to it that all their staff are fully trained. “They must know the law and they must understand their responsibilities for doing all in their power to ensure that pubs and clubs prevent disorder and crime,” said Home Office Minister, Mike O’Brien, recently. “And that includes drug penetration – not just violence and drunkenness.”

Mr O’Brien was addressing a gathering of people involved in the hospitality and leisure industry on their role in fighting crime and disorder. Speaking of the link between alcohol and crime, he outlined the way in which licensing law reform would help in the aim of allowing people to enjoy themselves in ways that do not annoy or threaten others. He said that the aim was to produce a White Paper “early in the New Year” and that legislation will follow when Parliamentary time permits: “I don’t know when that will be, and nor does Jack Straw.” He went on to say that there is plenty that can be done before any reform comes into effect. “The public, police officers, and local councillors have all indicated that alcohol-related crime and disorder is a significant problem now.”

Mike O’Brien listed the means local communities had to combat this, pointing out that key elements in any strategy must include the control of the environment inside and close to licensed premises and the reduction of the availability of alcohol to young people. “Anti-Social Behaviour Orders can be used to address public misuse of alcohol and bye-laws can be used by local authorities to make it an offence to consume alcohol in a designated public place after being warned by a police officer not to do so.” In addition, Mr O’Brien said that the Confiscation of Alcohol (Young Persons) Act deals with the problem of under-age drinking in public and that exclusion orders are available to bar people who commit offences on licensed premises from other public houses in the area. The latter have been used to considerable effect in York. He also pointed to the successful way that Northumbria Police had used the Inebriates Act, passed in 1898 when Lord Salisbury was Prime Minister, to keep away habitual drunkards firm licensed premises.

Any initiatives the police and local authorities take, however, will be wasted “unless the industry as a whole commits itself to the reduction of crime and disorder,” said Mr O’Brien. He praised the work of crime reduction partnerships and said that it was necessary to “get the licensed trade on board.” According to the minister, the consumption of alcohol had been part of this country’s “social fabric for more than a thousand years” – words reminiscent of those used by drink industry-funded agencies – and he wants to see people free to enjoy its use safe from violence and other crime. The government has shown itself amenable to industry involvement in the formation of alcohol policy (see Alert No. 3, 1999) and Mike O’Brien, speaking to his audience at the Licensee and Morning Advertiser Dinner, emphasised this: “I do not want the industry to be seen or talked about as part of the problem. I want you to be part of the solution.” Since any solution necessarily entails a reduction in sales, the minister’s hope may prove something of a challenge.

The question as to what the government will propose in its White Paper remains unanswered, at least by ministers.

White paper

Home Office Minister, Mike O’Brien, may say he does not know what the government is planning, but apparently the Editor of the Daily Telegraph does. The newspaper, which says it has obtained a draft of the White Paper on liquor licensing, published details of the proposed law only days after Mr O’Brien said that neither he nor Jack Straw knew when the White Paper would appear.

According to the draft the long-promised White Paper will permit supermarkets to sell alcohol at any hour of the day and night. There will also be stronger measures to prevent the sale of drink to children, with fines and imprisonment for anyone who fails to check the age of young customers.

At the moment different licensing regulations apply to pubs, shops, cafes, restaurants, theatres, cinemas, clubs, and discos. In future, they will be brought together under one set of rules. The plans give local licensing magistrates the responsibility for deciding the hours and conditions for each separate applicant. There had been speculation that these powers might be given to local authorities as a way of responding to what people in a particular area wanted.

Later hours?

Under the changes most pubs will be able to remain open until a later hour than at present. Instead of 11 p.m. closing in England, they will stay open until midnight or 1a.m. In town centres, the likelihood is that closing times will be between two and three in the morning. All-night opening will be allowed “in the right circumstances”, presumably when it is thought that it will not cause any nuisance.

The Telegraph quotes Jack Straw, the Home Secretary, writing a foreword to the White Paper, as saying: “The current licensing system is an amalgam of nineteenth century legislation, intended to suppress drunkenness and disorder, and later additions. The law is, therefore, complex and involves a great deal of unnecessary red tape.”

“Staggered” hours

The intention is to allow “staggered” closing times, where pubs and clubs in each locality empty at varying times. It is claimed that this would reduce the noise and violence caused by drunken clientele leaving licensed premises at the same time. Apparantly, it is believed that it would also make it easier to find a taxi home and cut the pressure on police and casualty units. Evidence from Edinburgh where such a scheme was introduced, and research done in Perth, Australia, where this kind of reform led to an upsurge in disturbance and crime, would seem to indicate that the opposite might be true.

It is said that later closing times are thought to reduce “last-minute bingeing” and, thus, rowdiness. Given the widespread bingeing culture it might simply be the case that last minute drinking would be transferred to a later time and greater quantities consumed.

No lower age limit

There will be no lowering of the age limit for which there was a call from various quarters, including, oddly enough, the Boy Scout and Girl Guide Associations. “The age limit of 18 is necessary to protect children from the damage that alcohol can do and to protect others from the behaviour of those who misuse alcohol while young and immature,” says the White Paper. Those aged 16 and 17 are already permitted to drink wine, cider, or beer with a meal in a pub.

Shops and off-licences will be faced with much stronger regulations to prevent them selling alcohol to under-18s. That someone “looked older” will no longer be an excuse. Traders will have a legal duty to establish that customers are the permitted age.

In order to minimise hooliganism, magistrates will be able to ban every off-licence or supermarket in the vicinity of a sports ground from selling alcohol during particular events. At the moment, the police may make a request, but can do nothing when faced with a refusal.

Most petrol stations in England and Wales are currently forbidden to sell alcohol but, according to the draft of the White Paper, this will be reversed if the proposals, recognising the growth in garage convenience stores, become law. The arguement is that nowadays in many rural areas the garage is the only village store.

Traders will have to qualify for a “personal licence” costing around £200. Like a driving licence, it will accrue penalty points if they break the rules and may be withdrawn. It will move with the licensee from one pub or shop to another. There will be new rules to curb rowdiness and noise in and around nightclubs.

The Home Secretary says in the report: “Ordinary people want – and should have – the opportunity to enjoy themselves with a drink or meal at any time without fear of violence, intimidation or disorder. We need modern laws to deal with an old problem. They should allow people to enjoy their leisure as they wish, provided that this does not disturb others.”

Advice online

With all the razzamataz that seems to be essential these days, the government has launched NHS Direct on-line, its new health advice website, and has expanded the NHS Direct phone service to cover 65 per cent of the country. NHS Direct includes advice on alcohol consumption and problems.

The new on-line service will allow the public to deal with the most common health problems themselves, with the back-up support of a nurse who can be telephoned directly. Some doctors have expressed concerns at the growth of “cyberchondria”.

Welcome from BMA

The NHS Direct healthcare guide has been composed after advice from doctors and nurse representatives and has been welcomed by doctors’ leaders. John Chisolm, Chairman of the BMA’s General Practitioners Committee (GPC) said:

I welcome the NHS Direct guide. Members of the GPC have been closely involved throughout its production. The guide will inform patients, empower them with the confidence to be more self-reliant and contribute significantly to ensuring the best use of GP’s valuable time. Both the book and the on-line service should help patients use our NHS more efficiently and appropriately.

A significant proportion of GPs’ time is spent dealing with alcohol-related problems and NHS Direct on-line has a large section on alcohol. This contains answers to many of the questions which are most frequently asked by the public. The present government’s circumspect attitude to alcohol policy has been commented on extensively (Alert, No.3, 1999) and the website begins in the same vein. “Alcohol can be a source of pleasure and enjoyment, and is a positive part of life for many people. We all know that a drink can sometimes help us to unwind or to relax with friends.” The use of the word “all” is either lazy writing or an insight into the attitude of the officials in the Department of Health who produced the text.

Daily benchmarks

The site discusses the levels of “sensible drinking” and daily benchmarks. The point is stressed that these daily benchmarks “apply to any day when you drink whether that’s every day, once or twice a week, or only occasionally. Most people drink different amounts on different occasions. But not drinking on some days doesn’t mean that you can drink more than the benchmark on days when you do drink.” The main problem arising from recommended limits is implicit in the emphasis put on the fact that these “are not targets to drink up to – it’s about how much alcohol your body can cope with on one day without any risk to your health.”

Having discussed safe quantities and the pleasure associated with consumption, On-line goes on to a section called “Effects of drinking too much”. Visitors to the site are warned that these are raised blood pressure, weight gain, accidents, liver damage, cancers of the mouth and throat, digestive problems, problems in pregnancy, and psychological and emotional problems.

“Health benefits”

“The health benefits of alcohol” are stated immediately afterwards. It is perhaps unfortunate that benefits are explicitly mentioned in the heading of the section whilst the damage done by alcohol to health are more neutrally described as “effects”. “Studies have shown that people who regularly drink small amounts of alcohol tend to live longer than people who don’t drink at all,” says the text. “This is because alcohol helps prevent coronary heart disease. Alcohol influences the amount of cholesterol in the bloodstream, and makes it less likely that clots will form.” The second half of this message is that “this protection is significant only when you reach a stage of life when coronary heart disease is likely to be a risk. For men this is over the age of 40 and for women it is after the menopause. The health benefits come from regularly drinking small amounts. The maximum benefit is achieved by drinking between 1 and 2 units of alcohol a day.”

As an afterthought it is mentioned that “if you don’t wish to drink alcohol there are other things you can do to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease. Stopping smoking, eating a healthy diet and taking regular exercise can also make a big difference.”

The section on changing drinking habits is useful and the advice is clearly expressed. The simple style adopted by the authors of the text is often inadequate to a complicated idea but is effective when setting out the six steps suggested for cutting down.

Useful tips

Those users of the site who believe that they might have a problem with alcohol will find the tips set out in Step Four particularly useful.

Step 4

|

The site, given that access to the Internet which such a large part of the population now has, may have considerable benefits. Many people with an alcohol problem, or simply the nagging feeling that they ought to look at their habits, will visit the site far more readily than they will discuss their drinking with a doctor, a family member, or a friend. However, the vital point is made that “if you continue to find it difficult to cut down, you should seek help from your doctor or a specialist agency. They can help whether you are concerned about your own drinking or someone else’s.”

The next sections are concerned with reasons to cut down on drinking -social, economic, emotional, and medical – and with “What alcohol is and what it does”

The final section is called “Helping someone to help themselves [sic]”. This contains vital advice and information for those people who are affected by another’s drinking. It gives some useful suggestions based on “things other people in your situation have tried”. These include:

|

The website address is: http://www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk

Oh brave, new world

Since the 1980s there has been a substantial shift in the style and pattern of drinking by teenagers resulting in heavier consumption and an increase in drinking to get drunk. This change reflects a wider transformation of the alcohol market and the start of what has been called “recreational drug wars” in which alcohol is marketed as one of a range of psychoactive drugs.

These are the main conclusions of the first of a new series of occasional papers published by The Institute of Alcohol Studies*. We are witnessing, according to Kevin Brain of the University of Manchester’s Social Policy Applied Research Centre, the emergence of a post-modern alcohol order marked by “bounded” and “un-bounded” hedonistic consumption.

Until about twenty years ago, the pattern of alcohol consumption in this country was well-established and long-standing. However, this was being eroded by the 1980s and the brewing industry began to take notice. “It started to target a new generation of youth drinkers, both male and female, who demanded a greater range of alcohol products and different kinds of drinking venue from the traditional pub.” The young people growing up in the eighties and nineties were living in a post-industrial society with shifting patterns of leisure and consumption. Mr Brain makes the point that long before “the introduction of alcopops, the brewing industry had begun to design new alcohol products, and transform the pub, in an effort to capture these new customers.”

The preferences and habits of the youth market was of crucial importance to the drink industry. As the old institution of the community pub and the established patterns of drinking changed, the brewers saw it as a real, and to them disastrous, possibility that a generation would grow up looking to pills and powders for its highs and washing them down with nothing stronger than Perrier water. Between 1987 and 1992 pub attendance had fallen by 11 per cent and this trend was predicted to continue up to 20 per cent by 1997. “The industry’s response,” says Brain, “was to accelerate the process of re-commodifying alcohol products that it had begun in the eighties.” He uses the term “re-commodification” deliberately to emphasise the industry’s development of alcohol as though it were a new consumer product. There have been four key elements of this transformation:

- the development of designer drinks such as ice lagers, alcopops, white ciders, and buzz drinks;

- the increase in strength of alcohol products in a direct attempt to compete in the psychoactive market;

- sophisticated advertising campaigns to establish alcohol products as lifestyle indicators; and

- the opening of new outlets aimed at the young such as café bars, theme pubs, and club bars.

Kevin Brain reminds us that the “brewing industry’s attempt to recapture the youth drugs market has been referred to as a recreational drug wars.” Alcopops are the obvious example of the brewing industry’s aping youth drug culture in design and naming.

The stable drinking patterns of post-war years have not been replaced by anything which has any air of permanence. In the light of the constant release and rebranding of new alcohol products and the shifting fashions in venues, these patterns, at least as far as the young are concerned, are likely to continue to vary. One aspect seems unlikely to change and that is the steady increase in the amount of alcohol consumed at any one drinking session. “In 1990 the average number of units consumed [by 11-15 year olds] in a week was 0.8 which by 1996 had risen to 1.8. If non-drinkers are excluded… then average weekly consumption rose from 5.4 units a week in 1990 to 8.4 units in 1996.”

The paradox of the consumer society as experienced by a section of young people is highlighted by Kevin Brain’s paper. In the very act of creating the demand for products, society excludes its most vulnerable sections from enjoying their use. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to accept “the popular media image of young drinkers being out of control.” Modern consumers, we are told, are “calculating hedonists” and many contemporary young drinkers “mark out pleasure spaces in which they can plan to ‘let loose’ and engage in less restrained behaviour than they would have to in the formal, complex structures of institutional interdependence such as school [or] work.” However, not all young people are able to exist within the pattern of control and move towards what Brain calls “unbounded hedonistic consumption”. They lack the means to pursue the consumer good life. “Lacking educational success, careers, and ways of constructing meaningful identities, they play around in the margins of society. Here drinking, drug taking, and other risk behaviours all merge in styles of spectacular consumption.”

Kevin Brain conducted extensive research among some of the most deprived teenagers in Manchester and their comments are eloquent of the problems of the post-modern alcohol order:

*Youth, Alcohol, and the Emergence of the Post-Modern Alcohol Order, Kevin J Brain, Institute of Alcohol studies, Occasional Paper No 1 January 2000 (pdf 325kb).

UK tops league again

Almost 5 million teenagers in the European Union have used heroin at least once, according to the 1999 report of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) The Monitoring Centre, which is based in Portugal, was created in 1994 to provide European Union leaders with reliable statistics to help them co-ordinate drug policies.

The annual report estimates that one in five15-year-olds across the EU has tried cannabis, which increases to a quarter of those in their 20s. In England and Wales, Ireland, Denmark and Spain up to 40 per cent of those aged between 16 and 34 admit to having used cannabis. One in five teenagers in England and Wales is thought to have sniffed solvents, which have moved to second place in the table of most abused substance.

EMCDDA estimates that, out of a total population of 375 million, fewer than 1.5 million can be classified as problem drug users, but abuse is spreading and is highest in Britain, Italy, and Luxembourg. In Europe about 20 people a day die from drug abuse. The highest rate of fatalities is in Ireland and Greece whilst France and Belgium have the lowest.

Apart from cannabis, England and Wales also top the league in the use of ecstasy, amphetamines and LSD, followed by the Republic of Ireland and the Netherlands. The report also says that, as far as teenage schoolchildren are concerned, England and Wales again have the worse drugs record.

On the positive side, the report says cannabis use among teenagers in England and Wales “has stabilised or even decreased”, whereas it is still on the rise in other EU countries. Almost half of the entire heroin seized in the EU in 1997 was intercepted in Great Britain, which has consistently had the most drug seizures every year since 1995.

Drug-related HIV infection rates among intravenous drug users were 32 per cent in Spain but only 1 per cent in England and Wales. The agency estimates 40 million people have tried cannabis, out of an EU population of 375 million. As many as five million may have tried heroin, and the problem is spreading beyond big cities to towns and rural areas.

The report warns: “While in general heroin is more prevalent in urban areas, it is spreading to smaller towns and rural areas. There are also continuing reports of heroin smoking by new groups.”

It estimates that up to 5 per cent of young European adults – 3 per cent of all adults – have tried cocaine, the highest rates being in France and Spain. As far as the criminal implications of use are concerned, ESPAD found that cannabis use is now rarely prosecuted across Europe and is decriminalised to all intents and purposes in a number of countries, such as Portugal, Spain, and Italy. However, the use of ecstasy is declining in popularity. Nevertheless drug arrests and seizures are rising across Europe. Drug offenders now make up half the prison population in some countries, and up to 90 per cent of prisoners are reported to be using drugs.

The report states: “Although the trend in many member states is to reduce the emphasis on prosecuting and imprisoning… police arrests and indicators of drug use in prison suggest some contradiction between theory and practice.”

It adds that fewer drug users are now contracting AIDS – down to only 1 per cent in Britain – but hepatitis B and C infections are becoming worryingly common.

Increase in cardiovascular disease

The amount of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the population increased in 1998 according to a new survey by the Department of Health*. This finding is against the trend of recent years of continuous decline in the prevalence of coronary heart disease and strokes. It is not at the moment known whether the 1998 result is an abnormality or whether it indicates an halt to the underlying trend of improvement.

The debate of the role of alcohol and cardiovascular disease continues with the case for the protective effect of moderate drinking being frequently made. If the effect can best be described by the famous J shaped curve, with moderate drinkers enjoying greater cardiovascular protection than non-drinkers, then those who drink at higher levels are most at risk. Other factors, such as obesity, smoking, and level of exercise, as well as alcohol will have played a role in the increase of cardiovascular disease.

Alcohol consumption did not show any significant change among men from 1994 to 1998, but rose among women. Nevertheless, in 1998 on average men were still drinking well over twice as much as women. There was no consistent trend in smoking prevalence detected between 1994 and 1998, although there was evidence of an increase in smoking prevalence in those aged 16-24.

The proportion with a CVD condition such as angina, heart attack, stroke, heart murmur, abnormal heart rhythm, other heart trouble, diabetes, or high blood pressure was 28 per cent for both men and women. Excluding those with high blood pressure, the proportion was 16 per cent for men and 14 per cent for women.

7 per cent of men and 5 per cent of women reported a history of Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) which includes angina and heart attack. With the addition of stroke the proportions rose to 9 per cent for men and 6 per cent for women.

Men in the lower social classes were more than twice as likely to suffer strokes and the proportion was only marginally better in women. The proportion of women drinking more than 14 units of alcohol a week was at lower levels in manual social classes whilst, in men, variation by social class did not follow a clear pattern.

Of men who had an alcoholic drink in the past week, the proportion of those who had drunk at least 8 units on at least one day during that week increased progressively from Social Class I (24 per cent) to Social Class V (44 per cent). The proportion of women drinkers who had drunk at least 6 units on at least one day followed a similar pattern, 11 per cent in Social Class I and 23 per cent in Social Class V.

The survey says that 28 per cent of men and 27 per cent of women reported smoking cigarettes. Smoking prevalence varies greatly with household income, being lowest amongst those with the highest income.

* Health survey for England: cardiovascular Disease ’98. Summary of key findings, Department of Health.

In Memoriam: Bernard Braine

The Right Honourable the Lord Braine of Wheatley, PC died on 5th January, 2000, at the age of 85.

For over twenty years Sir Bernard Braine was the voice of alcohol prevention policy in the House of Commons and he was proud to be asked by Sir Keith Joseph, the then Secretary of State for Health, to be Chairman of the National Council on Alcoholism, the precurser of Alcohol Concern, to reorganise it and make it a suitable recipient of government funds. When he became chairman in 1973, there were four alcohol information centres in England: nine years later, when he left the post, the number had increased tenfold.

For over twenty years Sir Bernard Braine was the voice of alcohol prevention policy in the House of Commons and he was proud to be asked by Sir Keith Joseph, the then Secretary of State for Health, to be Chairman of the National Council on Alcoholism, the precurser of Alcohol Concern, to reorganise it and make it a suitable recipient of government funds. When he became chairman in 1973, there were four alcohol information centres in England: nine years later, when he left the post, the number had increased tenfold.

Together with this extension of information and counselling services for problem drinkers and their families, a voluntary alcohol counsellor training scheme was inaugurated which is still in existence today. In 1977 Sir Bernard was responsible for the report “Alcohol and Work” which became known as the Braine Report. The Health and Safety Executive was later to acknowledge that this report provided the stimulus for the growth of programmes to tackle workplace alcohol problems.

In 1975 the NCA advocated the “high risk offender” procedure, a measure both designed to improve road safety and to assist in the early identification and treatment of problem drinkers. Sir Bernard, both in Parliament and outside, pressed for the implementation of this policy, which was finally adopted in stages by the Department of Transport during the 1980s.

During Parliamentary debates Sir Bernard never missed an appropriate opportunity to raise the level of awareness and understanding of alcohol problems. He will be remembered for his steadfast and often single-handed resistance to measures which he thought would increase alcohol problems in society.

At the time of the 1988 Licensing Act, in representations to the Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, he made the case for a coordinated governmental response to alcohol problems. As a result, the Inter-departmental Ministerial Group on Alcohol Misuse came into being.

Lord Braine, as he became on leaving the Commons, had a wide range of interests. He was a leading campaigner against abortion and was chairman of the All Party Pro-Life Committee, which spans both Houses. He was the founder and first chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Drugs Committee. He worked for many years in the cause of human rights. Throughout his time in Parliament he remained an advocate of the death penalty.

Lord Braine, as he became on leaving the Commons, had a wide range of interests. He was a leading campaigner against abortion and was chairman of the All Party Pro-Life Committee, which spans both Houses. He was the founder and first chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Drugs Committee. He worked for many years in the cause of human rights. Throughout his time in Parliament he remained an advocate of the death penalty.

When Vaclav Havel, the Czech campaigner for democracy, was thrown into prison by the Communists in the 1970s and his Prague Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted was proscribed, Sir Bernard joined hands with the late Joseph Jostin, a distinguished Czech journalist, to found the UK Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted. Together they worked tirelessly for Havel’s release.

When Havel visited London as President of Czechoslovakia it was Sir Bernard who was asked by the Czechoslovak community in London to greet him.

He also fought for the “disappeared ones” in Argentina and the oppressed in the Soviet Union. He was a determined opponent of apartheid in South Africa and Chinese misrule in Tibet.

As a tribute to Lord Braine we reprint an interview he gave to Andrew McNeill and which first appeared in this magazine in 1990 to mark his forty years in the House of Commons.

AM Where did you grow up and what was your family background?

BB I was born in Ealing on Midsummer’s day 1914 but during the War we moved to my grandmother’s house in Kew. I suppose that my family was middle class. My father was a civil servant in the Admiralty, and my mother, though born in London, had German parents who came here in the 1880s. She died when I was six and my brother was three. My father married again and we moved to Golders Green. Later we moved back to Kew.

AM You went to Hendon School. What did you do when you left?

BB I sat for a civil service entrance examination when I was 17 and joined the Inland Revenue.

AM Had it been your ambition to be a civil servant?

BB No. I was interested in politics in my very early days. I loved history and still do, and my headmaster wanted me to go to university. But it was 1931, we were in the middle of the slump. I had a younger brother and sister and my father was bringing us up on his own. He thought that the civil service offered a secure career. So that’s where I went.

AM How aware were you of the depression?

BB I was conscious that there was much unemployment and pressing social problems. Indeed, I remember the General Strike which took place when I was twelve.

AM Many people were attracted to socialism during the 1930s. Were you ever tempted to go in that direction?

BB Not really, though there was a period when I might have done so. For one thing there were family connections. My father had had socialist sympathies and my mother’s family had been German Social Democrats. My step-mother’s brother, Dr. T.P. Conwell-Evans, was private secretary to the Minister of Agriculture in the first Labour Government. So there were these family threads that might have pulled me towards the Labour Party. But as it was I joined the Young Conservatives in 1933 and have remained a middle ground Tory ever since. Of course, I could see what was happening and where it might lead. I was horrified by the rise of Hitler. I saw the dangers posed by Oswald Mosley who had broken away from the Labour Party to found a fascist movement. I did not like what I read about Labour’s plans for state control and regulation and I became convinced that Labour’s socialism was wrong for Britain. And, of course, by the mid-1930’s social conditions were already improving. By 1937 I was the national Vice Chairman of the Young Conservatives and was thinking of standing for Parliament. In fact I was approved by the Party as a candidate at the age of 24.

AM Obviously your plans, like everyone’s, were interrupted by the war. Did you ever fear that the war would put a permanent stop to everything in the sense that Hitler would win?

BB No. I just could not conceive that Britain would lose the war although frankly until 1944 I had no idea how we were going to win it.

AM You joined the East Surrey Regiment in 1940 and were commissioned in the North Staffords. Was your own personal war a successful one?

BB I certainly enjoyed army life. One knew that there was a grim job to be done but the comradeship made it enjoyable. I was lucky and survived. I also believed the dictum that every private soldier carries a field marshal’s baton in his knapsack. The army really did offer opportunities to those of us prepared to take them. I served in West Africa, North West Europe, and South East Asia and ended as a Lieutenant-Colonel on Lord Mountbatten’s staff.

AM Did you ever consider staying in the army?

BB At the end of the war I was offered an opportunity of a regular commission but I had already made up my mind to go into politics. In fact I had stood as a candidate in the 1945 general election while still a serving soldier, but I was defeated. I was determined to go on and won the next time round. It may sound odd but I felt that that was my destiny.

AM So you felt you were being called. How clear were you about what it was you were being called to do?

BB By the end of the war I had a very clear idea of the sort of society I wanted to see. It was not a class society. I never thought in those terms. Coming as I did from a modest family background there was no room for that. I believed that people get on through their own merit and should be given the chance to do so. I expressed my ideas in my book “Tory Democracy” published in 1947. Colleagues at Westminster told me in later years that it had influenced them to become Conservative.

AM You had already made a name for yourself when you got into Parliament in 1950. One newspaper published an article featuring five young hopefuls who should be watched: Reginald Maudling, Ian Macleod, Ted Heath, Enoch Powell, and Bernard Braine. Are any of these others on your list of people who have most impressed you in your forty years in Parliament?

BB Macleod and Powell were outstanding. I served under Powell at the Ministry of Health and he was a great inspiration. Maudling was brilliant but threw away his chances. But to be fair there were those on the other side who were impressive too. I was fascinated by Gaitskell and Nye Bevan.

AM You were on the front bench, either in Government or Opposition, from 1960 but your ministerial career ended in 1970. Why was this and how did you feel about it?

BB I was never sacked from ministerial office. We lost the election in 1964. Heath called me back to front bench in 1974 but never gave me the job for which I had been groomed. I went home disappointed but my wife told me to regard it as an opportunity. She was quite right: from then on I would be my own man. And I have been. But I had greatly enjoyed my ministerial career, particularly at the Commonwealth Office under Duncan Sandys and at the Department of Health and I was very disappointed at not becoming ‘shadow’ Minister of Health.

AM You have been deeply involved in the human rights field for many years.

BB Yes, in many parts of the world. My attitude over the Falklands crisis, for example, was determined by my knowledge of the appalling cruelty of the Argentine fascist dictatorship towards their own people. It was unthinkable that British inhabitants in the Falklands, who had lived under the rule of law, could be handed over to a cruel and repellent fascist government.

AM Do you see human rights as the link between all the causes you’ve espoused?

BB Yes, I do. There must be freedom if we are to improve the human condition but freedom is not licence. You don’t have to look very far to see the misery that stems alcohol abuse, drugs, crime, and pressures on the family and to see that society is in peril. It’s not just in Britain. The problems are worse in some other countries but we haven’t got very much to be proud of here when you look at the total picture.

AM What would you most like to be remembered for?

BB What matters is whether what one has done has been effective. I would place my work at the National Council on Alcoholism high on my list because we did make an impact. We made a real difference. And when one thinks of the social cost and misery caused by alcohol abuse the work was certainly worth doing.

AM And human rights?

BB Getting people freed who have been sent to prison for speaking up against tyranny or preventing them being sent there is very satisfying. I am a great admirer of the work of Amnesty International. If it did not exist it would have to be invented. Totalitarian regimes seek to blot out the identities of their victims. Our task has been to ensure that the victims are never forgotten. Ridicule and contempt for the tyrants is a very effective weapon.

AM Can you give some examples?

BB They are legion. Sakharov was one. The brave psychiatrist Anatoly Karyagin, imprisoned for refusing to certify as insane persons whom he knew were sane, was another. They were freed finally because of campaigns waged all over the world.

AM And Vaclav Havel?

BB He had been imprisoned for no crime known to any civilised nation simply for telling the truth about the Czech Communist regime. He could have purchased his freedom at any time if he had been prepared to bend the knee to his oppressors. He refused for two reasons: he had committed no crime and if he capitulated he would leave behind in captivity his fellow prisoners of conscience. He knew that if he did that he would give credence to the lies and cruelties of the system. He knew that the only way to defeat the lie was to stand valiantly for truth. He is one of the heroes of our time. I was proud to work for his release from prison in the early 1980’s. When I welcomed him on his recent visit to London on behalf of Parliament it was one of the most moving moments of my life.

AM How would you sum it all up?

BB I am proud of what I have done in the field of human rights and elsewhere, though others have done much more. I am only saddened by cases where we failed. But then, that is politics. There is no finality – the ideal we seek, as a wise man once said, is not an inn at which we can put up but a journey we must undertake.

Welsh Assembly and drug policy

One of the questions arising from the devolution of power to the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament is whether those bodies will have control over their own drug and alcohol policies or whether these will be dictated from Whitehall.

There was disquiet among alcohol and drug workers after a recent meeting with members of the Welsh Assembly. The impression was that the relevant politicians did not understand the issues and had little background knowledge.

Many at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Welsh Council on Alcohol & Other Drugs, believed that the new National Assembly was neither able to deliver treatment and prevention programmes in Wales nor decide on its priorities. “Committee discussions in the Assembly are inadequate,” commented David Melding, a Conservative Assembly Member, and pointed out that committees, dominated as they are by the Labour party, often allow less than thirty minutes for important discussions. Dr Dai Lloyd, a Plaid Cymru AM and a general practitioner, said that many Assembly Members “need to get into the real world and experience the string of patients presenting with alcohol and drug problems at their local surgeries.”

It was clear that at the grass roots, there are a number of overworked and under-resourced agencies dealing with the results of substance misuse. Many of these agencies were left wondering whether the assembly government shares their commitment and whether it can provide the resources to enable them to tackle the problem. Commenting on the meeting, Iestyn Davies, Deputy Director of the Welsh Council said, “Serious questions have to be asked. We need to know that the new devolved government will listen and, more importantly, respond to the needs of service users and professionals in Wales. We are currently awaiting the new Welsh Strategy on Substance Misuse and as yet we are not filled with confidence that the assembly will be able to deal with this important issue.”

Figures recently published by the Welsh Drug and Alcohol Unit show that, whilst referrals to treatment in Wales have increased when compared with previous years, the number of young people under 20 being referred has decreased markedly. Despite this, 19 year olds constitute 20 per cent of new notifications of substance misuse. This is still significantly higher than in England or Scotland. “Substance misuse in Wales follows a radically different pattern to that in England and Scotland,” said Mr Davies. “We need a tailor-made plan for Wales based on what works here. We don’t just need a rehash of the English strategy, Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain.”

The Assembly’s only response so far to Wales’ drug problem has been to disband the professional advisory body supporting the development of policy and to substitute a committee which has only met four times. It is reported that many of the alcohol and drug workers felt that Jane Hutt, the Labour cabinet member, showed little in-depth knowledge when she spoke at the meeting. There was a concern that the new Substance Misuse Advisory Panel (SMAP) would not have an adequate knowledge base to influence government policy significantly or even to keep it up to date. Commenting on the demise of the Welsh Advisory Committee on Drug and Alcohol Misuse, Consultant Clinical Psychologist Dr Richard Pates noted, “When the…committee was disbanded in April the inclusion of [Drug Action Team] chair people on the new [Panel] was welcomed and necessary. However, the lack of individuals with specific drug and alcohol knowledge and experience…is a serious omission.” This arrangement has led many to presume that political expediency was the only reason for replacing the old forum.

For many the arrival of the National Assembly signalled a new era for the development and implementation of local solutions to complex problems. However, Iestyn Davies summed up the feelings of many workers: “At present, one can only assume from the current response to the problems of substance misuse, that government by the unelected was better than government by the uninformed.”

Breath testing looms for drunken sailors

Splicing the mainbrace looks like joining weavils in biscuits and walking the plank as part of the maritime past. The Government says that laws are needed to bring seafarers into line with motorists and train drivers and the consultation document issued by the Department of the Environment, Transport, and the Regions (DETR) proposes breath tests for all sailors in coastal and inland waterways whether they are naval, merchant, or simply out in the Mirror dinghy.

There are more than two million users of leisure craft who would be affected by the measure. Drivers of speedboats, who are subject to far fewer regulations in the United Kingdom than in most continental countries, and jet-ski riders, who pose an increasing problem in crowded waters, will be breathalysed if there is suspicion that they are over the limit. Owners of larger yachts might feel particularly targeted: the tradition of convivial entertaining on board is longstanding. There are more practical restraints on sailors racing a Laser.

The DETR consultation paper says it is time to make “drink-sailing” a criminal offence and that the police should carry out the breath-tests on captains and crew members suspected of being drunk. Anyone over the limit could be fined and banned from sailing. Random tests are not likely to be introduced. Initial reactions from yachtsmen were not favourable. Whilst most felt that breath-tests for shipping was a reasonable proposition, there were objections to breathalysing people using small sailing boats.

Speaking to The Daily Telegraph, James Stevens, of the Royal Yachting Association, said: “This is totally unnecessary. The great pleasure of yachting is getting on board and opening a bottle of wine. There are a few idiots who take boats out when they are drunk but breath-tests will not stop them. People may think that we are a bunch of yellow-wellied, gin-swilling toffs but the vast majority of yachties are responsible and we take safety seriously. Most harbours already have bye-laws that ban anybody taking out a boat while under the influence of drink. That system works very well. We don’t need national laws.”

Some sailors argue that breath-test laws would be unenforceable. One is quoted as saying: “It’s very hard to catch a boat at sea – a motor boat might be doing 50 knots. And it would be expensive to have police patrols everywhere. Who would pay for it?” However, it is unlikely that even the most landlubberly of ministers envisage police launches hailing yachts under sail and requesting that they “pull over”. The proposed measures are aimed primarily at commercial shipping and presumably would only be used against leisure craft users when involved in an accident. Anyone who has been caught by the wash of a speedboat or alarmed at the basic skills of a jet-ski driver will welcome anything which increases the safety of water users.

A spokesman for Numast, the seafarers’ union, said that the shipping industry had introduced strict rules on drinking, including pre-employment screening and random tests in recent years. He said: “The idea of the drunken sailor is a myth. We don’t need new laws but we will go along with them.” It is nevertheless the case that problems with alcohol abuse often arise among sailors who can be on board ship for lengthy periods with only routine duties to perform.

I want to be an addict

Jonathan Chick reviews Addiction is a choice by Jeffrey Schaler.

Chicago: Open Court Publishing Co.

People can give up smoking or harmful drinking without the assistance of counsellors, doctors or programmes. To Dr Schaler, this means that their way of consuming these substance is therefore under their control in the same way as it is for others of us who change a habit. He decries those who ‘keep on telling the public that addicts physically cannot stop doing whatever it is that they do’. He says an old word, ‘addiction’ has taken on a ‘new-fangled meaning’, that the addicted person ‘literally cannot stop’. This is easily disproved, he says, quoting experiments and examples where people deemed addicted stop when circumstances change.

I think he has set up a straw man. Addiction researchers and therapists do not use such absolute terms. A more typical view would be as follows. There are some people who drink alcohol or use drugs who find it more difficult to alter their patterns than others who use, or who are subject to motivational forces which are rather different. There is a continuum of difficulty to change. A mosaic of factors – learnt habits, social forces, genetic predispositions, and drug pharmacology – interact to influence drug consumption. What we perceive as choice presumably has something to do with the balance in this mosaic of positive and negative incentives.

In a book entitled ‘Addiction is a Choice’, the reader might expect a central discussion of what choice is. The issue is whether our behaviour is determined by our chemical memories and the stimuli we meet; whether the experience we have of making choices is an illusion. Dr Schaler sets the ‘free will model’ as the opposite of ‘the disease model’, but skirts round the free-will conundrum, except for page 68-69 tucked away in a chapter entitled ‘Who are the Addiction treatment providers’. Here he leaves us with the enigmatic statement: ‘Acceptance of the free-will model does not require taking a position on the philosophical question of free-will and determinism. A determinist could accept the free-will model, as long as the determinist recognised a practical distinction between voluntary and involuntary human action (which determinists do).’ Clarification, please.

Dr Schaler is concerned that in some US courts an offender’s claim to have been addicted has changed the Court’s judgement. I do not know of such cases in Europe, where a guilty verdict in a drug or alcohol dependent person would only be modified if there was definite evidence of hallucinations or delusions, or dementia. However, the medical report may affect the Court’s disposal – for less severe crimes offenders may be offered the option of treatment as part of probation, or sentence is deferred while the progress of the offender who has chosen to take treatment is monitored. Dr Schaler also believes some US Courts acted wrongly in mandating offenders to treatments involving A.A., which at times he seems to see more as a religious movement than a treatment.

The book is a set of essays. Some are polemical. In others he cites from the peer reviewed international literature, though his summaries are not always balanced. For example, he quotes Davies’ 1962 paper ‘Normal drinking in recovered alcohol addicts’. Although he includes the later 20 year follow-up in his bibliography, his text does not mention that only two of Davies’ original seven stayed clear of serious alcohol problems. In our Edinburgh two year follow-up study, ‘Advice versus extended treatment’, which he quotes elsewhere, he would have seen that only 6 out of 152 sustained problem-free drinking. Dr Schaler quotes our study as one which supports his thesis that ‘addiction treatment is a scam’. In fact, our study showed that over the two years the treatment group accumulated less social harm than the advice-only group.

You will not find ‘genetics’ or ‘heredity’ in the index. However, he lampoons it in his straw man’s credo: ‘Credo of the Disease Model – 8. The fact the addiction (alcoholism) runs in families means that it is a genetic disease.’ He credits the ‘disease concept’ proponents with little intelligence! Any farmer knows that the expression of a gene depends on its interaction with the environment – different soils or climates produce different harvests from the same gene. Genetic research tells us that a drug’s effects on the brain are not the same in all individuals. The reward/aversion payoffs associated with that drug may differ depending on the genetic signature on brain cells, as well as on the past experience of that individual and interacting social and psychological factors. The strength of associations which are laid down in the brain for a given drug will vary between individuals. Dr Schaler does not attempt to review this evidence. This will frustrate many of his readers who will have heard of the advances in this field, be it the twin and adoption studies, or perhaps the mice whose 5HT1B receptor genes had been experimentally knocked out and who showed exaggerated nervous reaction to stress, high alcohol intake, high cocaine injecting and impulsive behaviour (Crabbe et al, 1996).

I share Dr Schaler’s concern that commercial clinics can abuse the disease concept, persuading employers or families to coerce the ‘sick person’ into treatment which she does not wish and perhaps do not even need. Like him, I shudder at the way ‘denial’ is used as a defining symptom of illness by some clinics. If I deny that I have diabetes, does that mean I am likely to have diabetes?

As part of his attack on ‘the sanctity of the Therapeutic State and the economic interests of the growing treatment industry’, Dr Schaler exposes ‘The Project Match cover-up’: ‘The study showed that no type of treatment for alcoholism was significantly better or worse than any other, and in particular, that ‘treatment’ by free self-help groups is at least as good as ‘treatment’ by paid professionals. Every effort was made to suppress these findings and to smear those who publicised them’. He believes the Project Match team feared that the results would lead to closing down professional treatments in favour of AA.

However, the results are not suppressed. They are available to all in the scientific literature. At least for clients from an environment highly supportive of drinking, what Dr Schaler says is correct: patients offered Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) tended to do slightly better than those receiving the two other psychological treatments (Longabough et al, 1998). However, the TSF group were not simply told to go to AA meetings. They were offered 12 individual counselling sessions with a paid person who helped them clarify their motives in seeking help, discussed the AA approach , and facilitated them getting to AA meetings . When simply telling clients to attend AA was tested (versus sending them to a residential ‘hospital’ programme – Walsh et al, (1992)), employees treated through a company’s employee assistance programme did better with hospital treatment than ‘being sent to AA’. This study is not mentioned by Dr Schaler. Dr Schaler is angry at the cost of Project Match, but that is a separate matter.

In the Project Match chapter, Dr Schaler gives AA as an example of the approach he favours – encouraging ‘individualism and autonomy’. Elsewhere he attacks AA as a ‘religious cult’ promulgating the dangerous notion of the ‘disease model’. (Perhaps AA groups vary?)

Maybe it is useful, at times, for people to conceive of their predicament as linked in part to some variant in their physiology. It cannot be a question of fact whether their plight is a disease. Disease is only a concept. It can be defined in dozens of ways (Rezneck, 1987). But Dr Schaler is right to warn of the danger that people might use the disease concept to absolve themselves from responsibility.

Certainly, some of us in a given circumstance will find it harder to resist a particular desire than the next person. However, society expects us to be informed about the risks and to avoid putting ourselves into high risk situations if someone else could be harmed. We need to be reminded of harmful consequences of too ready use of the disease concept – and Dr Schaler’s book helps to keep a balance.

References:-

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Feller DJ, Hen R, Wenger CD, Lessov CN, Schafer GL (1966) Elevated alcohol consumption in null mutant mice lacking 5-HT1B serotonin receptors Nature Genetics 14: 98-101

- Longabough R, Wirtz PW, Zweben A and Stout RL (1998). Network support for drinking, Alcoholics Anonymous and long-term matching effects. Addiction; 93:1313-1334

- Reznek L. (1987) The Nature of Disease London: Routledge

- Walsh DC, Hingson R, Merrigan D. et al (1992) A randomised trial of treatment options for alcohol-abusing workers. New England Journal of Medicine 325, 775-782

- Dr Jonathan Chick is a Consultant Psychiatrist at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital and Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry at Edinburgh University. He has advised government bodies in UK, Brazil, Australia, Canada, and USA on public health and treatment issues related to alcohol, health, and social problems. His research in early detection and intervention for problem drinkers and relapse prevention treatments for alcohol dependence is recognised internationally. His study on counselling for problem drinkers in the general hospital is the third most cited paper in the field of alcoholism treatment research in the world literature.

Whisky’s Awa’

Andrew Varley reviews The Scottish Nation: 1700 – 200 by T.M. Devine, published by Allen Lane, the Penquin Press

From Tam O’Shanter to Rab C. Nesbitt, the caricature of the drink-sodden Scotsman is well established. How far does this conform to reality? T.M. Devine’s The Scottish Nation: 1700-2000 traces the development of North Britain since the time of the Union. During the intervening centuries the Scots have had the fun of running the Empire and exercising political and commercial power far out of proportion to their numbers. At the same time, and despite the admonitory presence of the Kirk, they have gained the reputation of world-class drinkers. I used to stay with a clan chief, a delightful and lovable man with a deserved reputation for unrivalled genealogical scholarship – he also wrote wonderfully entertaining and discursive essays masquerading as book reviews. He drank like a fish and so, unless they were exceptionally strong-minded or weak-headed, did the friends with whom he filled his house (“Rule One: always help yourself to a drink; rule two, never put that drink down on a book”). On one occasion I asked a fellow guest, a Maharaja who spent his time between Switzerland, New York, and the Côte d’Azur, what he considered his nationality to be. “Scotch, by absorption,” he replied.

As a boy I considered myself Scotch (although, until I accepted that by paternal descent and domicile I was English, I would have said Scots)* and my earliest memories of Scotland involve my grandfather, to other people a terrifying figure, to me a benign companion, who used to boast that he had prevented any pubs being opened in Rothesay. That must have been when he was the minister there, sometime in the late twenties, I assume. Whether his success in repelling the brewers had any measurable effect on how much the islanders drank is open to debate. Highlanders, whoever has had theoretical authority over them, have always had an independent outlook on life. It was largely they who introduced whisky as a popular drink in the Lowlands at the latter end of the eighteenth century. It was their skill, acquired in remote and chilly glens, which was needed to establish the huge number of illegal shebeens which proliferated in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and the other towns of the industrial revolution. One of the two peculiarities of the drink culture of Scotland noted by Professor Devine is that whisky came to be preferred to beer and was responsible for the huge increase in drunkenness recorded by many observers. Professor Devine’s work is wide in scope and its section on drink is necessarily brief. Nevertheless, the story he tells indicates the profound effect alcohol had on life in Scotland – and still has, I dare say.

In 1850 a leader in The Scotsman said: “That Scotland is, pretty near at least, the most drunken nation on the face of the earth is a fact never quite capable of denial.” The second distinct feature of drinking in Scotland, says Professor Devine, was the easy availability of alcohol compared to England, where, for example, it was illegal from 1830 for ale-houses to sell spirits. There were huge numbers of public houses in the growing towns and countless illegal dram shops, many selling a noxious mixture of whisky and methylated spirits. In 1903, when it was necessary to be 16 to buy alcohol in England, in Scotland the legal age was still 14. In the 1830s official figures showed that in Scotland the annual consumption of spirits was two and a half gallons per head of the population. This was not only seven times the quantity recorded a hundred years later, it was clearly, given all those illegal shebeens, a considerable underestimate.

There was more to drinking in Scotland than simple availability and Professor Devine discusses its social and cultural roots. Drink was part of the ritual which marked most significant occasions, weddings and funerals, of course, but also the end of an apprenticeship, the completion of a business deal, and many more of life’s milestones. Industrial growth – and, of course, the Highland clearances – brought tens of thousands of migrants into the towns. The pub was the centre of social life, the source of companionship, the place to find work, and a brief opportunity to escape the squalor of the tenement.

Commentators often found it extraordinary that a country so given to intoxication should also be clerically dominated. The same could have been said of Ireland, but in Scotland the Kirk not only had a more puritanical cast of mind than the Catholic Church, it had the power of the establishment behind it. Until the nineteenth century, however, there was little identification between temperance and Christianity. The growth of evangelicalism in the Presbyterian church, influenced by Methodism south of the border, changed all that. Following the quartering of the duty on spirits in 1828, consumption trebled. The reaction was led by men like John Dunlop, who had written on Scottish drinking habits, and William Collins, the founder of the publishing house. In 1842 the great Irish temperance advocate Father Theobald Mathew addressed an audience of 50,000 in Glasgow and later induced 40,000 Irish immigrants to take the pledge. The Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland took up the temperance cause. Social reformers and clergymen alike saw drink as the curse of the working classes but, as elsewhere, were often divided as to cause and effect. Teetotalism was an important strand throughout the nineteenth century in Scottish radical politics, affecting both the co-operative movement and the Independent Labour Party. Partly as a consequence of this upsurge of feeling, spirit consumption had fallen dramatically by 1860 but then stabilised at a level where it remained until the 1900s.

Professor Devine has the breadth of vision of the genuine historian. Whilst analysing Scottish society with meticulous scholarship, he illuminates his subject with entertaining detail. How many who have drunkenly bawled out “The Wild Rover” know that it was composed as a temperance song. And Harry Lauder first made his name in the Saturday evening concerts organised by the Glasgow Abstainers Union. This was all part of a practical attempt to provide alternative entertainments to the pub. At a time when the the steamboats of the Clyde were known as floating drinking dens – hence, explains Professor Devine, the Scots term ‘steaming’ for drunken – there was a teetotal paddle-steamer provided as a rival attraction.

Organisations like the Band of Hope and the Catholic League of the Cross provided a sober focus for a wide range of the population and temperance became fashionable among the middle-classes. It was, however, by no means a bourgeois phenomenon. Labour leaders like Keir Hardie and Willie Gallagher received their political formation in temperance lodges. These lodges, like the Primrose League, and with comparable success, drew on Masonic ritual and their popularity stemmed in part from the colour and spectacle they provided.

Professor Devine notes an interesting variation in working-class drinking in nineteenth century Scotland. There was a move among respectable artisans towards drinking at home and a tendency for pubs to become the haunts of rougher elements. This went along with the virtual exclusion of women from the pub, a phenomenon which continued in Scotland right down to the 1960s. Professor Devine traces the commercialisation of leisure in Scotland, the improvements in travel, and the increasing opportunities to have fun without getting drunk. Trips to Loch Lomond, or “down the water”, were available to all but those at the very bottom of the social pile, and were often sponsored by temperance organisations.

Professor Devine devotes equal care to every significant aspect of Scottish life during his chosen three hundred years. The Scottish Nation: 1700-2000 is essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in the development of the United Kingdom. Drink is a small part of this history but it has had a profound effect.

* A lost cause, I suppose, but, in the embers of the ‘scotch’, ‘scots’, ‘scottish’ argument, I am with Miss Nancy Mitford and Mr A.J.P. Taylor. ‘Scotch’ is the English adjective. Fowler is uncharacteristically pusillanimous on the subject.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

How to shift the dial on alcohol policy in Europe

Florence Berteletti –

Eurocare

Anamaria Suciu –

Eurocare