In this month’s alert

Why the alcohol industry can’t afford to let us kick our drinking problem

Podcast feature

James Wilt, PhD candidate and author of ‘Drinking Up the Revolution’, writes that we aren’t talking enough about the influence of the alcohol industry on Britain’s unhealthy drinking habits and how alcohol’s ubiquity is largely due to “its commodification and deregulation by Big Alcohol”.

Wilt states that the industry has successfully maintained self-regulation and offloaded responsibility for harm on ‘problem’ users “especially through the discourse of ‘responsible drinking’”.

He argues that: “The crisis of alcohol-related harms is principally caused by the fact that the profit-motivated alcohol industry structurally incentivises higher-risk drinking”, highlighting that their profits would fall by £13 billion a year if drinkers consumed within the guidelines.

As well as limiting the alcohol lobby’s power – through advertising restrictions and restrictions on density and hours of sale – Wilt argues that there also “needs to be a massive expansion of free and public alcohol-specific healthcare for higher-risk drinkers that doesn’t demand sobriety as a condition of use, including managed alcohol programmes, therapy, medication-assisted treatment and psychiatric care”.

“Ultimately, this is about expanding opportunities for relaxation, socialising and pleasure in ways that don’t eventually kill, injure or harm.”

In our podcast we spoke to James Wilt about his Guardian article, as well as his new book: Drinking Up the Revolution: How to Smash Big Alcohol and Reclaim Working-Class Joy.

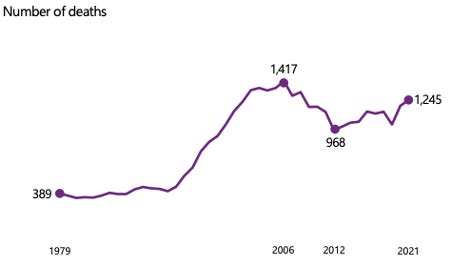

Alcohol-specific deaths in Scotland continue to rise

Alcohol-specific deaths increased in Scotland by 5% to 1,245 in 2021, according to the National Records of Scotland (NRS). This already follows a big increase of 17% from 2019 – 2020.

The NRS report says two-thirds of those who died were male and the average age was 59.7 for men and 58.7 for women.

Julie Ramsay, a statistician at NRS, said:

“Deaths attributed to alcohol were 5.6 times as likely in the most deprived areas of Scotland compared to the least deprived areas. This is more than the deprivation gap for all causes of death, which is 1.9.”

Alcohol Focus Scotland’s Alison Douglas said: “We seem to almost accept this toll as inevitable, but we should not. Each death can be prevented” – she called for minimum unit pricing to be increased to 65p and an emergency response on the same scale as the efforts to tackle the drug deaths crisis.

Prof Sir Ian Gilmore said:

“As it stands, there is no plan in place from the UK Government to use their reserved powers to curb this mounting crisis. Without a UK-wide alcohol strategy to ensure that evidence-based, life-saving policies are introduced to reduce our alcohol consumption and urgent investment is poured into treatment services, there is no hope for turning this tragic trend around.”

To MUP or not to MUP

Across the UK and Ireland there were a number of news stories relating to minimum unit pricing in August. The Times reported that two drug treatment service providers – David Liddell of The Scottish Drugs Forum and Annemarie Ward of Faces & Voices of Recovery UK – suggested that the increase in alcohol prices was driving people to use street drugs more.

In a joint letter from Alcohol Focus Scotland, Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), Scottish Recovery Consortium and Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs, the charities rebutted the suggestion that MUP is leading to increased drug use in Scotland. They highlighted that the available evidence shows quite the opposite.

Despite this, Welsh Conservative and Shadow Health Minister Russell George used it as evidence for MUP not working when criticising Welsh Labour’s MUP policy. He said:

“It has become increasingly clear that Labour’s minimum alcohol price is having a whole host of unintended consequences from pushing people to take drugs and sacrifice heating and eating, all the while failing to fulfil its very purpose to drive down heavy drinking.”

Across the Irish Sea, retailers in Northern Ireland are calling for MUP to be introduced in the country. It was introduced in the Republic of Ireland at the beginning of this year, and leaders of the Federation of Independent Retailers (The Fed) – which supports over 10,000 retailers across the UK and Ireland – have said introducing it in the North would “level the playing field” and allay fears of cross-border trading.

Joe Archibald, president of The Fed in Northern Ireland, said:

“One of the main benefits of MUP for smaller retailers with off-licences is the fact that the big multiples and supermarkets will have to charge the same prices, so they will no longer be able to undercut independents by selling cheaper alcohol as loss leaders. This should level things up and give everyone a fair crack of the whip.”

In the Irish Times towards the end of the month, journalist Mark Paul wrote that if MUP doesn’t have the desired impact of reducing harmful drinking, it should be scrapped, and duty rates should then be increased. He says the money could then be used by the state to fund health and poverty measures.

Paul also argued that the alcohol industry has a clear vested interest so people should assess its contributions through the prism of this self-interest. However he also states that those on the other side of the policy debate have developed a bias. He says those who campaigned for MUP have developed a vested interest in seeing the policy they fought for vindicated: “the zeal of the policy’s biggest cheerleaders means they are not necessarily neutral observers”.

Eunan McKinney of Alcohol Action Ireland hit back at this, stating that it is “wholly inaccurate” to draw an equivalence between the voice of public health and the alcohol industry:

“Our interest, for instance, is not a private, pecuniary interest whose insatiable appetite for revenue, and discount of science, seems to know no limit, but instead one that plainly seeks to reduce alcohol harm throughout society and improve public health.”

Alcohol harm to bystanders costs as much as harm to drinkers, at $20 billion

A new study by La Trobe’s Centre for Alcohol Policy Research suggests that two-thirds of Australian adults have been adversely affected by someone else’s alcohol consumption, costing the country an estimated $20 billion a year in emergency healthcare, caring and lost productivity.

The study says that bystanders bear almost 90% of the costs, with government agencies paying the rest.

Dr Jason Jiang from La Trobe, said:

“The burden to others from drinking is of the same general magnitude as the burden that drinkers impose on themselves and on response agencies serving them. This distinguishes alcohol from tobacco, for instance, where the burden of health harm to the smoker is much greater than the burden of second-hand smoke.”

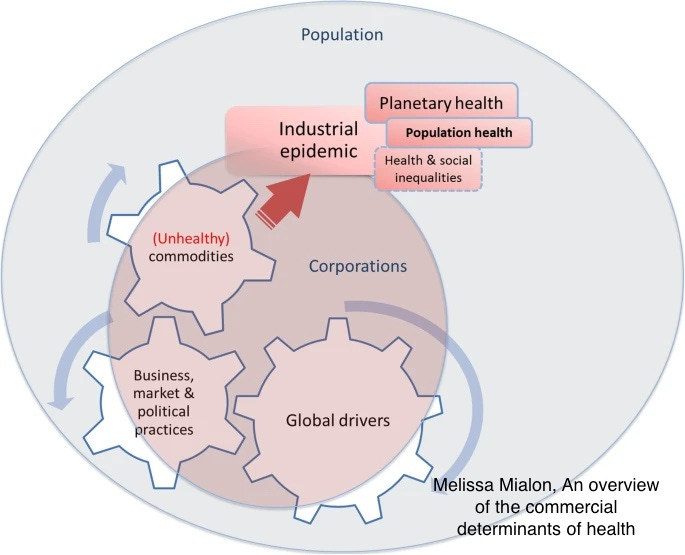

How local councils are working to reduce commercial determinants of health

In BMJ Letters, public health practitioner Amanda Pickard writes that local councils are beginning to “pull the available levers” to reduce commercial determinants of health (CDoH), from limiting takeaways, creating smoke-free places, restricting marketing, alcohol licensing and combating industry-sponsored educational materials.

She states that communicating the message about CDoH is important and that departments across councils can work together and with local politicians and elected members to influence decision making.

Industry tactics can be exposed to the public through community engagement, and the narrative and language can be changed: “reframing health away from the NHS response and towards the system and the structural and environmental antecedents of health, then embedding this in faculty and specialist training, as well as undergraduate medical curriculums.”

Pickard said:

“We still too often hear the term “lifestyle choices.” They are mostly not choices at all but the consequence of carefully crafted, heavily funded choice architecture by industry. Good progress is now being made in reframing tobacco use, which we need to build on with wider public health harms.

“Essentially, we can work to create our own public health playbook. The scale and power of industry does seem overwhelmingly huge sometimes, but collectively we can and are starting to fight back.”

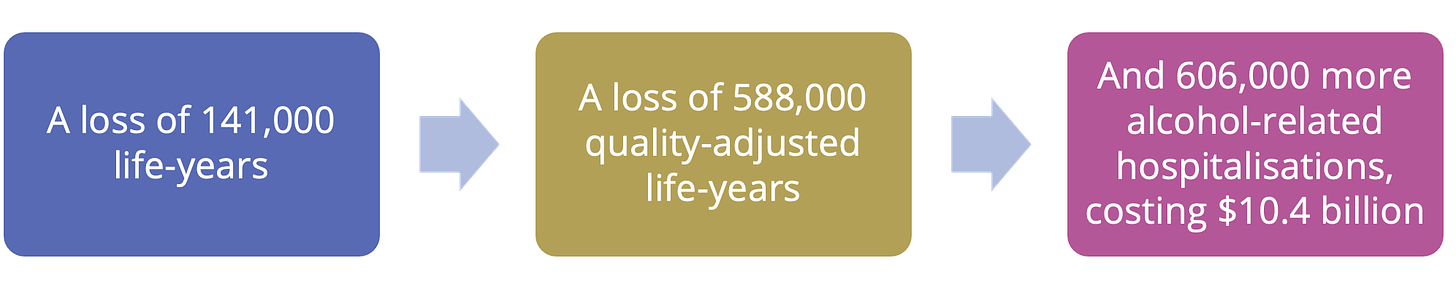

Pandemic drinking could lead to 600,000 more alcohol-related hospitalisations in the US

A modelling study in Addiction by research group RTI International projected future health and cost impacts of shifts in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

They modelled three scenarios: no change in drinking, increased drinking levels persist for 1 year, and levels persist for 5 years.

In their central scenario, where higher drinking levels persist for 1 year, they projected it will lead to:

If levels persist for 5 years, they projected that there would be:

The researchers conclude that:

“Understanding the short- and long-term consequences of increases in consumption during and after the pandemic provides critical information to clinicians, policymakers and public health agencies to more efficiently plan for health services and prepare for future public health emergencies in the United States and abroad.”

‘Sake Viva!’ Japan’s controversial drive to get younger generations to drink more

Japan’s tax agency has launched a national competition asking people to come up with ideas to get the younger generation to drink more alcohol.

Younger people in Japan drink less than older generations, meaning taxes from drinks like sake are steadily falling. In 1980 alcohol tax was 5% of revenue, and in 2020 was 1.7%

The ‘Sake Viva!’ campaign aims to make drinking seem more attractive and boost taxes, and asks 20–39-year-olds to share business ideas to increase drinking demand.

Following the news, some Twitter users criticised the idea, pointing out that the campaign is at odds with Japan’s health ministry guidance which suggests moderate drinking.

The article says that in response “Japan’s health ministry said that while it wasn’t involved in the campaign, it understood the spirit of the promotion was in line with its view that people should ‘drink responsibly’.”

The tax agency responded to queries from Bloomberg that it’s a business promotion to encourage growth and “in no way is it encouraging people to drink excessively”.

Half of cancers caused by smoking, alcohol and being overweight

Smoking, drinking alcohol, being overweight and other risk factors are responsible for almost half of all cancer deaths worldwide, according to a Global Burden of Disease study in the Lancet.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, and behavioural, metabolic, and environmental and occupational risk factors are responsible for almost 4.45 million cancer deaths a year, the study says, representing 44.4% of all cancer deaths.

Half of all male cancer deaths in 2019 (50.6%, or 2.88m) were due to estimated risk factors, compared with more than a third of all female cancer deaths (36.3%, or 1.58m).

The biggest cause of risk-attributable cancer deaths for both women and men globally was tracheal, bronchus and lung cancer. These account for 36.9% of all cancer deaths attributable to risk factors.

This was followed by cervical cancer (17.9%), colon and rectum cancer (15.8%) and breast cancer (11%) in women. In men, it was colon and rectum cancer (13.3%), oesophageal cancer (9.7%) and stomach cancer (6.6%).

The authors say that behavioural risk factors, including alcohol, represented the largest attributable burden:

“Most attributable cancer DALYs were accounted for by behavioural risk factors, such as tobacco use, alcohol use, unsafe sex, and dietary risks, suggesting a need for concerted efforts to address behavioural risk factors to effectively reduce cancer burden globally.”

While not all cases or deaths are preventable, Cancer Research UK says stopping smoking, cutting back on alcohol, maintaining a healthy weight, enjoying the sun safely and eating a balanced diet can all improve the odds.

Could using smaller bottles and glasses reduce wine consumption?

A study in Addiction looked at how using smaller bottles and glasses could impact the amount of wine consumed at home.

260 households consuming at least two bottles of wine a week were recruited, and were either asked to buy 750ml or 375ml bottles. They were further split by glass size, either 290ml or 350ml glasses

The results found weak evidence that smaller bottles reduced consumption: Households consumed on average 146 ml (3.6%) less wine when drinking from smaller bottles than from larger bottles.

The evidence for the effect of smaller glasses was stronger: households consumed on average 253 ml (6.5%) less wine when drinking from smaller glasses than from larger glasses.

ScotRail alcohol ban to remain for the “foreseeable future”

ScotRail introduced a ban on alcohol consumption on its trains in November 2020 to reduce the spread of Covid by helping to maintain physical distance between passengers.

The operator has now said the ban will remain for the “foreseeable future”. ScotRail is owned by the Scottish Government, and on Twitter stated that “The policy will be reviewed as part of the Scottish Government’s National Conversation on Rail”.

ScotRail’s service delivery director, David Simpson, said the move had been “successful, particularly in containing some of the antisocial behaviour alcohol could often generate on some services” but that he doubts it will be permanent.

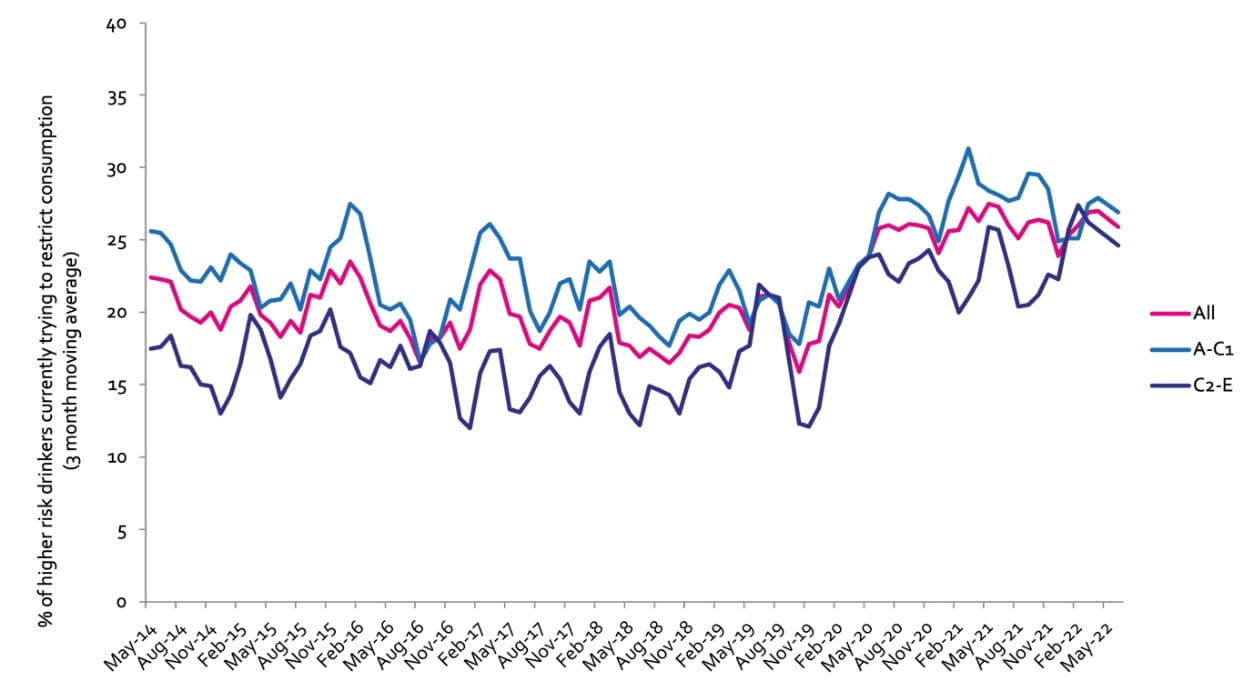

Alcohol Toolkit Study: update

The monthly data collected is from English households and began in March 2014. Each month involves a new representative sample of approximately 1,700 adults aged 16 and over.

See more data on the project website here.

Prevalence of increasing and higher risk drinking (AUDIT-C)

Increasing and higher risk drinking defined as those scoring >4 AUDIT-C. A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation

Currently trying to restrict consumption

A-C1: Professional to clerical occupation C2-E: Manual occupation; Question: Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses? Are you currently trying to restrict your alcohol consumption e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses?

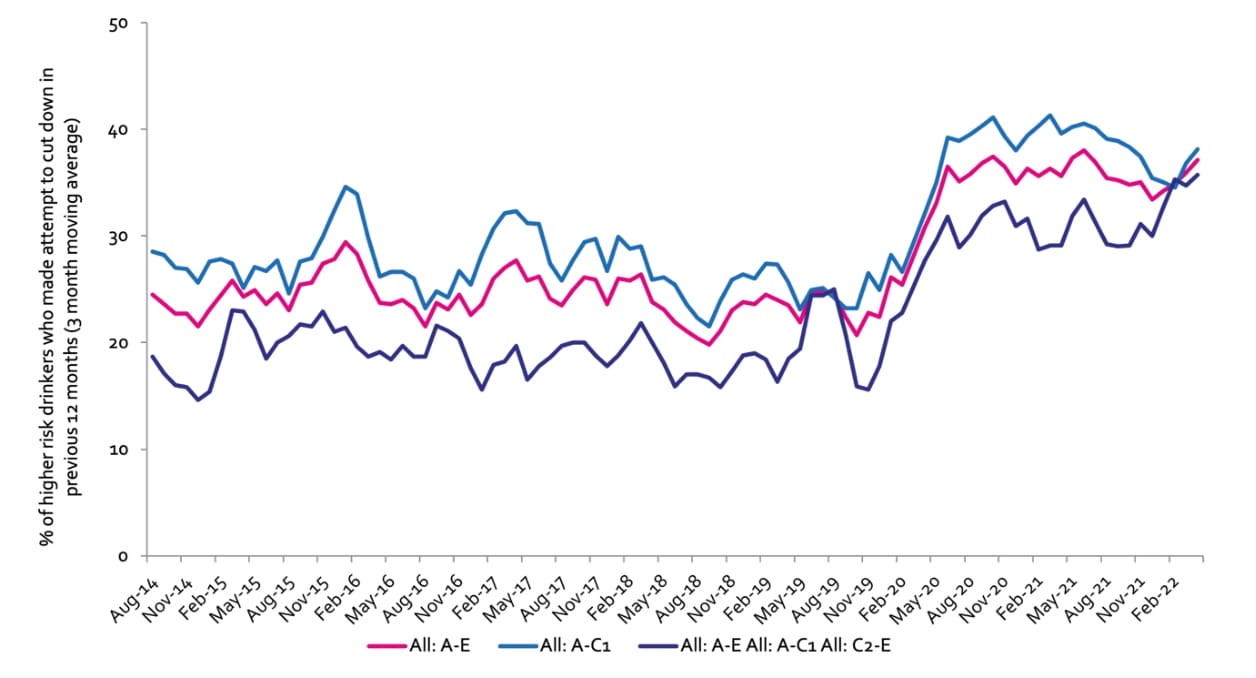

All past-year attempts to cut down or stop

Question: How many attempts to restrict your alcohol consumption have you made in the last 12 months (e.g. by drinking less, choosing lower strength alcohol or using smaller glasses)? Please include all attempts you have made in the last 12 months, whether or not they were successful, AND any attempt that you are currently making.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.