View this report

Summary

- Young people are more likely to be non-drinkers, drink within weekly low risk guidelines, and drink less regularly than most other age groups

- Young people are, however, relatively likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking

- Young men and women drink differently, and there are different patterns by age in men’s and women’s drinking

- Recently young people have been drinking less on almost all metrics of consumption than they used to

- The reasons young people drink are distinct from other age groups

Introduction

How much, what, where, when, and why people drink alcohol differs considerably across the lifespan. This is likely influenced both by changing social position and roles, and also by cohort – how you drink when you are young will influence how you drink when you are older.

The physical and social consequences of drinking also differ considerably, morbidity and mortality is more common in older groups, whether that’s from alcohol or other factors. Some groups face specific risks – underage people may be more vulnerable to setting long-term behaviours, working-age people will be at higher risk of work-based accidents, and older-people may be more vulnerable to chronic health consequences.

This series of briefings on alcohol through the life course will look at three different age groups: underage drinkers, young drinkers, and older drinkers. Understanding the patterns of drinking in different demographics matters as it enables us to identify risks and thus target policy solutions to particular groups.

What is a young person?

This briefing focuses mostly on those aged 16-24 years of age. Younger adolescents are covered by the underage drinking part of this series of briefings. This is to align with how data are collected, but it is worth noting that the Chief Medical Officer for England recommends that an alcohol-free childhood, up until 18, is the safest option [1].

Profile of young people’s drinking in the UK

Sources

The different constituent parts of the UK collect data in different ways, and as such are often not readily comparable. In England most of the data will be drawn from the 2018 NHS Digital’s Health Survey for England, focusing on the 16-24-year-old age group [2]. In Scotland an equivalent, the 2018 Scottish Health Survey will be used [3]. For Wales, the data used is from the 2018/19 National Survey for Wales [4]. In Northern Ireland the most up-to-date information on drinking which is readily available broken down by age group is from the 2013 Adult drinking patterns in northern Ireland, which uses the 18-29-year-old age grouping [5]. More recent whole adult population data are available in Northern Ireland, from the Health Survey for Northern Ireland 2018/19, but this does not allow ready access to the breakdown of data by age and is therefore largely not discussed in these briefings [6].

How many young people drink?

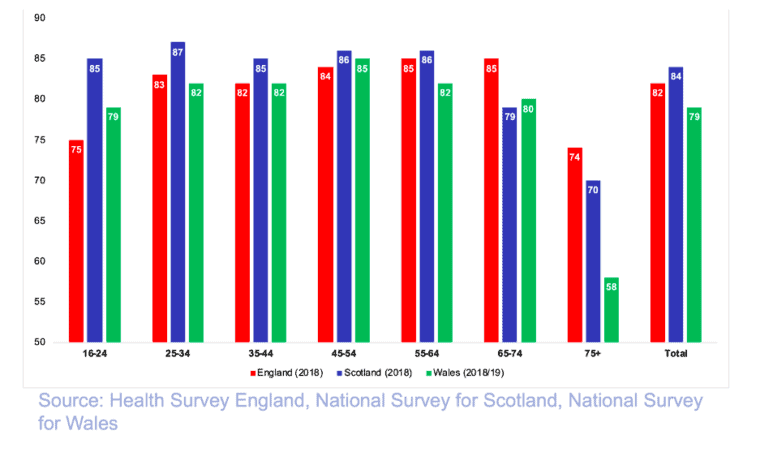

In England, around 75% of young people aged 16-24 consumed alcohol in the last year. This compares to around 82% of the general population; the gap between young people and all adults has widened since 2011.

In Scotland, 85% of young people (16-24) had consumed alcohol in the past year compared to 84% of all adults. Looking at changes over time this also appears to have fallen, in 2003 89% of 16-24-year-olds and 91% of all adults reported drinking once or more a year [7].

In Wales 79% of both 16-24-year-olds and all adults have drunk in the past year.

In Northern Ireland, statistics are collected for the 18-29-year-old age group.* 82% of them were drinkers in 2013, compared to 73% of the adult (in this case 18-75) population. This is compared to 79% and 70% respectively in 1999.

When gender specific data are available, young men are more likely to drink than young women, a pattern seen across people aged over 16 as a whole.

Figure 1 Proportion of 16-24-year-olds who drink, compared with all age groups

How much do young people drink?

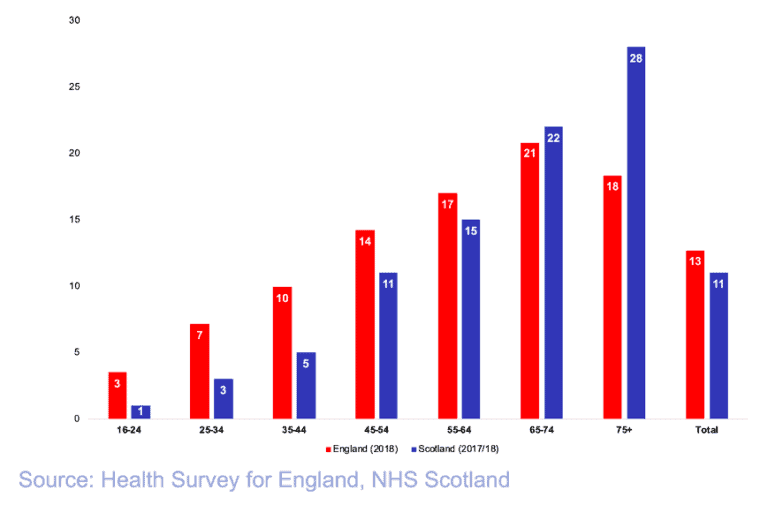

The chief medical officers recommend that men and women should not exceed 14 units of alcohol per week [8]. Overall, 17% of all people aged 16-24 consume more than 14 units per week in England. In England, the gap in alcohol intake between younger adult drinkers and older age cohorts has widened since 2011.

In Scotland, 22% do so, and in Wales it is 15%. The data for Northern Ireland is different as they are based on the old guidelines so not included in this briefing (low risk limit of 21 units/week for women and 28 units/week men).

In all three cases this is a lower likelihood of exceeding low-risk guidelines than all or most other age groups.

Women are less likely to exceed 14 units per week than men, which is true for all age groups. There may be some differences in the pattern in consuming over 14 units within each gender by age group.

How frequently do young people drink?

Young people are less frequent drinkers than all other age groups, although this is measured differently in the different parts of the UK.

In England, only 3% of 16-24-year-olds reported drinking on more than 4 days a week in the week before the survey.

In Scotland, the closest equivalent statistic is drinking on five or more days and only 1% of 16-24-year-olds had done that.

In Northern Ireland, 2% of 18-29-year-olds reported drinking on nearly every day the week before the survey.

The equivalent data are not readily available for Wales.

As with essentially all other measures of alcohol consumption the proportion of men drinking frequently exceeds women, with a similar pattern apparent in both genders.

Figure 2 Proportion of 16-24-year-olds who drank in the last week, compared with all age groups

Heavy episodic drinking

As well as the weekly guidelines, alcohol consumption per occasion is important as it is associated with some of the acute alcohol-related harms including injury and risk taking. Different thresholds for single episode drinking are used for men and women.

In England, those are >6/8 units on one occasion for women/men. In England, 16-24-year-olds are the second most likely age group (behind 25-34), for both genders, to have consumed >6/8 on their heaviest drinking occasion in the past week, with 19% having done so. Regarding trends over time, in England the gap between those aged 16-24 and all adults in likelihood of drinking >6/8 units on the heaviest occasion has deceased considerably since the mid 2000s but has since flattened.

In Northern Ireland, drinking >7/10 on one occasion for women/men is used, and half of those aged 18-29 had done so – the highest of any age group. Data for Scotland are not readily available by age group, and data for Wales are broken down into larger age ranges (16-44) and therefore neither are directly comparable with the other two nations.

Health outcomes for young people

Overview of health and social harms amongst young people

A wide range of harms associate with alcohol consumption in young populations. An overview of the impact on undergraduate students in the US found a range of associations with alcohol [9], and a similar set of risks were found in a UK review of reviews, which looked at children and young people aged 5-25 years [10]. Some of these factors are listed below:

- Road traffic accidents

- Injuries

- Risky sexual behaviour

- Physical and sexual assault

- Suicide

- Involvement with police or the criminal justice system

- Alcohol use disorder and dependence

- Alcohol-related blackouts

- Alcohol poisoning

- Lower academic performance

- Mental health problems and feelings of depression

The review of reviews also identified an association with chronic health problems including appetite changes, eczema, headaches, sleep disturbances and rarely even cirrhosis. Additionally, brain development continues until around the age of 20, meaning that those aged 16-20 may also be vulnerable to some of the developmental consequences seen in children (see our briefing on underage drinking).

Hospital admissions among young people

Scotland and England both collect age-group specific hospital admissions rates, however they use different definitions for an alcohol-related hospital admission so cannot be compared. In England, admissions for those under the age of 40 have declined since the end of the last decade since the beginning of the 2010s although there was a notable rise between 2017/18 and 2018/19, which was found in hospital admissions for all age groups [11].

Scotland reports data for a narrower, younger age group, those aged 11-25. Alcohol-related hospital admissions in that bracket declined since the late 2000s, but have plateaued over the last few years and show hints of rising again [12].

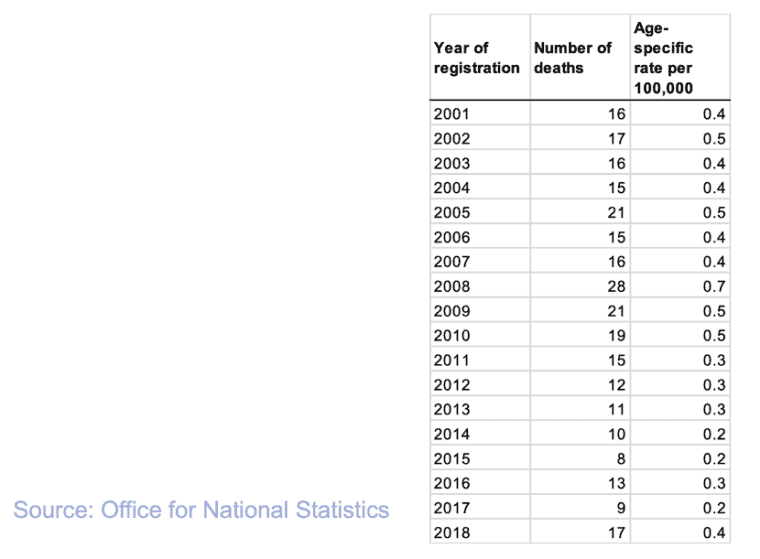

Alcohol-specific mortality amongst young people

UK-wide figures are available for alcohol-specific mortality trends amongst young people [13]. As visible from this graph alcohol-specific mortality amongst young people is rare and has fluctuated but remained broadly flat [14]. While the rate of alcohol-specific mortality is relatively low, all-cause mortality is also low for this age group, which means that in England, alcohol is the leading risk factor for ill-health, disability, and early mortality amongst 15-49-year-olds [15].

Figure 3 Alcohol-specific death rates, 20-24-year-olds, UK, 2001 to 2018

The context of young people’s drinking

Why do young people drink?

Overall, young people aged 16-24 drink less overall, and less frequently, than older adults. However, young people are more likely to drink heavily on single occasions. This pattern may well speak to the specific social role that alcohol plays for young people who are in a transitional stage of their life.

Work in 2010 involving interviews with young people found that the consumption of alcohol amongst young adults was for the pursuit of intoxication, with heavy episodic drinking in particular seen as not having substantial health consequences as it was occasional. Alcohol was found to occupy a key position in young people’s social lives [16].

More recent work in 2017 focused on a specific group of young people, those in first year at university who were staying in University accommodation. In this group, alcohol – and in particular heavy episodic drinking – was again seen as a way of quickly building social bonds. This was relevant, as new students’ anxieties were often focused around a concern of not forming close social connections at University [17].

Understanding the drivers of young people’s drinking matters as it can guide policy decisions. Both of these pieces of work identified that external influences also played an important role: for example, substantial amounts of alcohol marketing that encouraged and normalized heavy episodic drinking. Existing messaging around ‘sensible’ drinking and the health consequences of drinking is also perceived to be not relevant, as it does not align with the motivations young people have for drinking.

As with drinking in older age groups, the World Health Organization’s ‘best buys’ [18] of controls on price, marketing and availability are likely to reduce drinking among young adults. Price-based interventions such as minimum unit pricing may be particularly effective for young people, as expenditure on alcohol is something young people self-identify as reducing their consumption [19]. For more information on these effective policies see the Price, Marketing, and Availability of alcohol briefings.

Why is alcohol consumption falling amongst young people?

The reasons for the fall in alcohol consumption among underage adolescents are discussed in detail in our briefing on underage drinkers.

There has been a similar fall in alcohol consumption among young people, whether that is measured by proportion of drinkers, amount consumed each week, or the prevalence of heavy episodic drinking, has been fallen among young people in recent years but has since plateaued.

Understanding why can again provide insights into areas that could form effective policy targets. Work in 2018 from Ng Fat et al [20]. investigating these trends in young people’s drinking in England between 2005-15, concluding that:

- The rise in non-drinkers is largely attributable to a rise in life-time abstainers;

- The increases in non-drinkers were found across a wide range of subgroups within the 16-24 years age bracket including socio-economic status and geographic location;

- There was a particularly large increase in non-drinkers in the 16-17 age group (from 28% in 2005 to 48% in 2015);

- Non-drinking did not significantly rise in non-White ethnicities (although non-drinker remained higher amongst non-White ethnicities);

- The rise in non-drinking was correlated with reducing harmful drinking patterns including mean units of alcohol consumed and heavy episodic drinking.

* Northern Ireland figures not directly comparable with the other UK nations, so do not appear in figure 1

- Chief Medical Officer for England (2009). Guidance on the consumption of alcohol by children and young people.

- NHS Digital (2019). Health Survey for England 2018: children’s health.

- Scottish Government (2020). The Scottish health survey 2018: main report – revised 2020.

- Welsh Government (last updated 28 February 2020). National survey for Wales: results viewer.

- Northern Ireland Department of Health (2014). Adult drinking patterns in Northern Ireland survey 2013.

- Northern Ireland Department of Health (2020). Health survey Northern Ireland: first results.

- Scottish Government (2008). The Scottish health Survey: revised alcohol consumption estimates.

- Chief Medical Officers (2016). UK Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines.

- White A, Hingson R. (2013) The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res.

- Newbury-Birch, D et al (2009). Impact of alcohol consumption on young people: a systematic review of published reviews. Department for Children, Schools, and Families, and Newcastle University.

- Public Health England (accessed 19 June 2020). Local alcohol profiles for England.

- ScotPHO (accessed 19 June 2020). ScotPHO profiles.

- For the difference between alcohol-specific and alcohol-related hospital admissions see: The Institute of Alcohol Studies (accessed 19 June 2020). How alcohol mortality and morbidity rates are calculated in the UK

- Office for National Statistics (2019). Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2018.

- Public Health England (2016). ‘The public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies’

- Seamn, P and Ikegwuonu T (2010). Drinking to belong: understanding young adult’s alcohol use within social networks. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Brown, R and Murphy, S (2020). Alcohol and social connectedness for new residential university students: implications for alcohol harm reduction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44:2, 216-23.

- World Health Organization (2017). Tackling NCDs: “best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases.

- Seamn, P and Ikegwuonu T (2010). Drinking to belong: understanding young adult’s alcohol use within social networks. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Ng Fat, L. et al. Investigating the growing trend of non-drinking among young people; analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys in England 2005-2015.

View this report