View this report

Summary

- Men at all ages are more likely to drink alcohol than their female counterparts

- Men overall are also more likely to develop dependency issues through their drinking, compared with women

- Beers and ciders are the most commonly consumed type of beverage for men

- Alcohol has a significant influence on male mental health, with men more likely than women to experience ‘externalising’ problems, including substance abuse

- The UK-wide the rate of alcohol-specific deaths amongst men is more than double that of women, and the rate of admissions for alcohol is also significantly higher

- Alcohol appears to be more involved in male violence than female, specifically in the proportion of cases where the offender/s were male

Introduction

Men are more likely to drink alcohol, more likely to drink at levels above recommended low-risk guidelines, and more likely to have alcohol dependency than women. Men experience some specific alcohol-related harms and also experience a greater degree of overall health harm, as measured by hospitalisations and deaths, compared to women. The harms of alcohol are not restricted to the drinker, and men’s alcohol consumption can lead to harm to others. The relationship between men, masculine and other identities, and alcohol is complex. It is also influenced by alcohol marketing and public policies, leaving considerable scope to reduce the level of alcohol harm experienced by men through regulatory measures.

The pattern in male drinking

The 2018 Health Survey for England found that 86% of men drank alcohol in the past year, whereas 79% of women had done so [1]. Men at all ages were more likely to drink alcohol than their female counterparts.

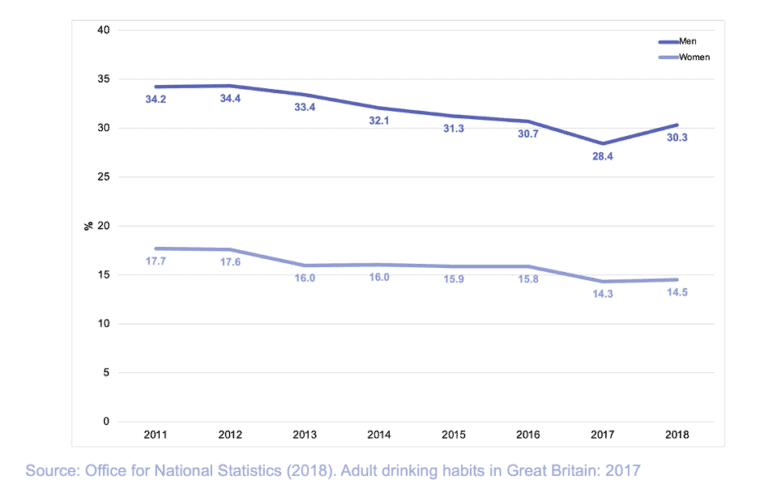

Regarding regular drinking, 10% of men, compared to 5% of women, report consuming alcohol almost every day. Looking specifically at the UK Chief Medical Officers’ low-risk drinking guidelines, since 2011 the proportion of men drinking over 14 units per week appears to have fallen from 34% to around 30%, however it has remained consistently higher than women, with men being approximately twice as likely to do so (figure 1).

Figure 1 Proportion of adults (16 and over) drinking alcohol above the Chief Medical Officers’ low-risk weekly drinking guidelines (more than 14 units per week)

The definitions used to measure single occasion drinking are from those used by the Office of National Statistics and are higher for men than for women, with ‘binge drinking’ defined as consuming more than eight units in one day for men and six for women [2]. Nevertheless, the Health Survey for England found that men are still more likely to exceed them: in the last week 19% of men had consumed more than eight units in one session, whereas 12% of women had consumed more than six units.

Although alcohol consumption data is collected and reported differently in different parts of the UK, the same pattern of men drinking more than women is seen. In Scotland, in 2018 the mean weekly alcohol consumption in men was around 80% higher than women [3]. In Wales, in 2018/19 men were more likely to drink above the weekly low-risk guidelines in every age group, with the prevalence more than double in some age groups [4]. In Northern Ireland, in 2017/18 31% of men (aged over 18 years) consumed more than 14 units per week, whereas just 9% of women did so [5].

Types of drink consumed by men

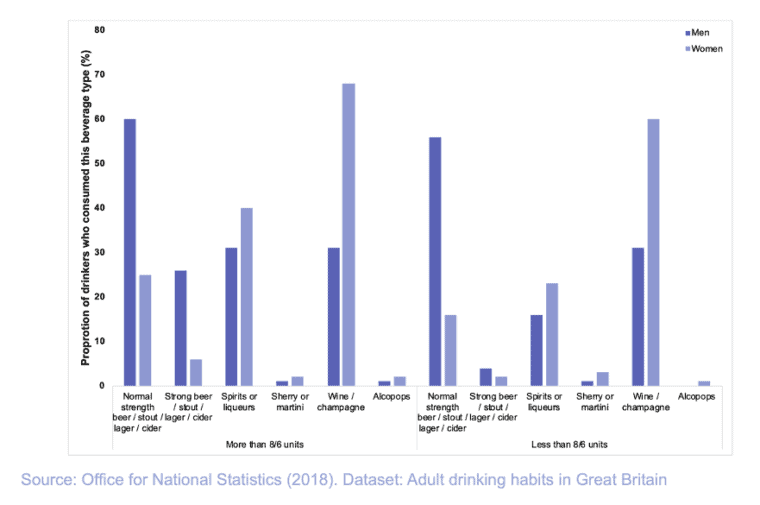

Type of drink consumed is not published as part of the Health Survey for England. However, the Office for National Statistics publishes tables on type of drink consumed on heaviest drinking day, separated by whether more than 8/6 units (men/women) were consumed on the day for Great Britain (see figure 2) [6]. In general terms, on their heaviest drinking day normal strength beer or cider appears to be the most popular drink amongst men. In contrast, wine or champagne is the most popular for women (for more information about women and alcohol see the IAS Women and alcohol briefing). Amongst men who drank more than eight units on their heaviest drinking day stronger beer, cider, and spirits were more popular than among men who drank less, a pattern also seen in women.

Figure 2 Beverage type consumed on heaviest drinking day in Great Britain in 2017, by sex

The effect of socio-economic status on alcohol consumption and harm

In a similar pattern to that seen in women, greater levels of deprivation are associated with higher levels of non-drinking in men. Despite this, as is the case for women, men with higher levels of deprivation are more likely to experience alcohol-related harm than their less deprived counterparts. This is known as the alcohol harm paradox [7].

For more detail of the relationship between alcohol and socio-economic inequality, read our Alcohol and health inequalities briefing.

What are the health impacts of alcohol for men?

In England, alcohol is the leading risk factor for ill-health, early mortality, and disability amongst those aged 15 to 49 years, and the fifth leading risk factor for ill-health across all age groups [8]. Many of the effects of alcohol, including its impacts on cardiovascular disease, dementia, a number of cancers, liver disease, mental health, accidents, immune system, and skeleton are experienced by both men and women, however men experience a greater degree of alcohol-related morbidity and mortality as discussed below [9].

Some of its impacts are specific to men. For example, alcohol can cause sexual problems such as impotence and premature ejaculation [10]. There is evidence that alcohol may impair male fertility: a study of young men in Denmark found that habitually consuming five or more units (~7.5 UK units) per week was associated with reduced semen quality, with larger effects seen at higher levels of consumption [11].

Alcohol also has a significant influence on male mental health. It appears that men are more likely than women to experience ‘externalising’ problems, including substance abuse [12], and rates of alcohol dependence are higher in men than women [13]. The relationship between alcohol and men’s mental health is discussed in more detail in the Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP) and IAS report, Men and alcohol: key issues [14].

Deaths due to alcohol

Both hospitalisations and deaths from alcohol-related causes are higher in men than women. In 2018, the UK-wide the rate of alcohol-specific deaths amongst men (16.4 per 100,000) is more than double that of women (7.6 per 100,000) [15]. Alcohol-specific deaths include only deaths that are wholly attributable to alcohol.

In England, alcohol-related deaths (this includes conditions such as bowel cancer which are partially, but not wholly, attributable to alcohol) are also around twice as high amongst men than women (67.2 and 28.7 per 100,000 respectively) [16]. Over the last ten years the rate of alcohol-related mortality has remained relatively static, as has the difference between men and women.

While not directly comparable, due to using a different measure of whether a condition is related to alcohol, this pattern is repeated in Scotland: men were around twice as likely to die from an alcohol attributable condition than women in 2015 [17]. Similarly, around twice as many alcohol-attributable deaths occurred in Wales in men compared to women in 2015-2017 [18].

Hospital admissions due to alcohol

In England, alcohol-related hospital admissions are also higher in men than in women. Using the ‘narrow’ definition of alcohol-related hospital admissions the rate amongst men is around twice the rate found in women (850 and 494 per 100,000 respectively). Over the last 10 years, admissions have increased among both sexes, with the gap remaining relatively constant [19].

As with deaths, admissions due to alcohol are measured differently in Scotland and Wales, but the same pattern of the rate in men being approximately twice that of the rate in women is found [20].

Men’s drinking and harm to others

Alcohol has numerous harms to those other than the drinker, including traffic accidents, property damage, violence, mental health, and sexual assault [21]. These harms impact, and result from, men’s and women’s alcohol consumption at different rates.

Women are more likely to experience intimate partner violence from a male partner than men are from female partners [22]. For general violence, in England and Wales 39% of victims of violence believe that the perpetrator was under the influence of alcohol at the time of the assault. Alcohol appears to be more involved in male violence than female, with alcohol a factor in 43% of cases were the where the offender/s were male, and only in 28% of cases of when the offender/s were female [23]. Alcohol also has a clear association with sexual harassment and assault (for more information read our Domestic abuse, sexual assault, and child abuse briefing.

Men’s relationship to alcohol

The Institute of Alcohol Studies and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems explored the relationship between men and alcohol in detail in a series of seminars which took place throughout 2019/20 [24].

Alongside the physical impacts, this series detailed the role alcohol plays in the construction of male identity, how this intersects with culture, race, and class, and the causative role of alcohol marketing in this relationship. Importantly, the negative effects of alcohol on men are not insurmountable. Whilst there are considerable gaps in research, for example the impact upon LGBT+ individuals or the role of alcohol in fatherhood, evidence exists to indicate a wide range of effective changes in policy and services that could address alcohol harm in men.

- NHS Digital (2019). Health survey for England 2018 adult’s health-related behaviours

- Office for National Statistics (2018). Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017

- Giles L, Richardson E. Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy: Monitoring Report 2020. Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland; 2020

- Public Health Wale Observatory (accessed November 2020). Alcohol in Wales

- Northern Ireland Department of Health (2019). Tables from health survey Northern Ireland

- ONS (2018). Dataset: Adult drinking habits in Great Britain

- Smith K & Foster J (2014). Alcohol, Health Inequalities and the Harm Paradox: Why some groups face greater problems despite consuming less alcohol

- PHE (2016). The public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies

- NHS (accessed November 2020). Alcohol misuse: risks

- NHS (accessed November 2020). Alcohol misuse: risks

- Jensen TK, Gottschau M, Madsen JOB, et al (2014). Habitual alcohol consumption associated with reduced semen quality and changes in reproductive hormones; a cross-sectional study among 1221 young Danish men. BMJ Open

- Smith, D., Mouzon, D., and Elliott, M. (2018). Reviewing the assumptions about men’s mental health: an exploration of the gender binary. American Journal of Men’s Health

- Public Health England (2016). Health matters: harmful drinking and alcohol dependence

- The Institute of Alcohol Studies and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (September 2020) ‘Men and Alcohol: Key Issues’

- ONS (2019). Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2018

- Public Health England (accessed November 2020). Local Alcohol Profiles for England.

- ScotPHO (2018). Hospital admissions, deaths and overall burden of disease attributable to alcohol consumption in Scotland

- Public Health Wale Observatory (accessed November 2020). Alcohol in Wales.

- Public Health England (accessed November 2020). Local Alcohol Profiles for England

- ScotPHO (2018). Hospital admissions, deaths and overall burden of disease attributable to alcohol consumption in Scotland; and Public Health Wale Observatory (accessed November 2020). Alcohol in Wales

- Public Health England (2019). The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others.

- Jones, L. et al. (2019). Rapid evidence review: the role of alcohol in contributing to violence in intimate partner relationships. Alcohol Change UK.

- ONS (2019). The nature of violent crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2018.

- The Institute of Alcohol Studies and Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (September 2020) ‘Men and Alcohol: Key Issues’

View this report