View this report

Summary

- Aspects of the on- and off-trade have been identified as influencing rates of alcohol-related crime

- Research into crime and disorder in urban areas has tended to identify a correlation between the density of licensed premises in a locality and the numbers of people present

- Evidence from both natural experiments and modelling studies support a link between alcohol pricing and overall crime

- The presence of youth orientated ‘vertical drinking’ establishments where drinking is an end in itself is a feature of the night time economy also identified as a cause of high risk consumption

- Public health bodies have suggested that increased temporal availability may serve to increase rates of alcohol-related crime

- Several other policy initiatives have been tried in an attempt to tackle the drivers of alcohol-related crime, with varying degrees of success

Introduction

Aspects of the on- and off-trade have been identified as influencing rates of alcohol-related crime. In recent years, two important parallel trends in the night time economy and off-trade sales have been evident:

- The growth of the night time economy and the associated problems of alcohol-related crime and disorder in town and city centres

- An overall relative decline in the proportion of alcohol consumed in on-licence premises and a growth in the proportion of alcohol purchased from off-licence premises and consumed at home.

Density of premises

Research into crime and disorder in urban areas has tended to identify a correlation between the density of licensed premises in a locality and the numbers of people present. This can be explained by the combination of licensed outlets clustered in close proximity to one another – especially in town centres – with the high crowd density that occurs at night time, where resources such as transport may be scarce, which can lead to acts of aggression fuelled by the intoxication of alcohol.

Similar associations have been identified between alcohol outlet density and other forms of violence, as well as sexual offences.

The evidence

Research published in 2018 analysing crime rates and alcohol outlet density in Scotland found that crime rates, including violence and sexual offences ‘were consistently and significantly higher in areas with more alcohol outlets. This relationship was found for total outlets, on-sales outlets and off-sales outlets.’ These crime rates included crimes of violence and sexual offences [1].

Studies of violence in Cardiff found that serious violence in the city’s entertainment thoroughfare was directly proportional to the capacity of licensed premises in that street [2].

A recent study on female alcohol consumption in and around licensed premises also found that a significant relationship between both factors, with acts of aggression most commonly motivated by an emotional reaction or to address a grievance [3].

United States (US) based research on the relationship between alcohol and violence in the local vicinity found that [4]:

- In a study of Camden, New Jersey, neighbourhoods with higher alcohol outlet density had more violent crime (including homicide, rape, assault, and robbery). This association was strong even when other neighbourhood characteristics such as poverty and age of residents were taken into account

- In a study of 74 cities in Los Angeles County, California, a higher density of alcohol outlets was associated with more violence, even when levels of unemployment, age, ethnic and racial characteristics and other community characteristics were taken into account

- In a six-year study of changes in numbers of alcohol outlets in 551 urban and rural zip code areas in California, an increase in the number of bars and off-premise places (eg liquor, convenience and grocery stores) was related to an increase in the rate of violence.

From this, one report drew the following conclusions [5]:

- In neighborhoods [sic] where there are many outlets that sell high-alcohol beer and spirits, more violent assaults occur

- Large taverns and nightclubs and similar establishments that are primarily devoted to drinking have higher rates of assaults among customers

Solutions

In the UK, there has been a rapid increase in the capacity of licensed premises in city centres nationwide. In Manchester, for example, the number of people who could fit into all the city centre’s pubs and clubs rose by 240% between 1997 and 2001 [6]. Central Cardiff has more licensing capacity per square metre any other city centre in the UK. Their night time economy is estimated to be worth £413 million a year, employing over 11,000 people [7]. But the city has also become a case study for explaining the rise in alcohol-related crime and social disorder on Britain’s streets.

The UK has been shown to have higher levels of alcohol outlets density than the US and Australia [8], and it has been suggested there would need to be a reduction of more than 10% in density in England and Wales to see an impact on alcohol-related harms [9]. It is however, important to note that while density of premises in the UK has increased, overall rates of alcohol-related crimes have reduced, which points towards the complex interplay of different factors which influence both consumption and crime.

The introduction of Cumulative Impact Policies (CIP) was intended to reduce the level of crime and social disorder occurring in the night time economy. They were designed to prevent the proliferation of licensed premises concentrating in a designated area by making it harder to obtain an alcohol licence in areas where there are high levels of alcohol-related problems. There has been mixed evidence on the impact CIPs have had since their introduction. They do not reduce, but rather slow down, the growth of the night time economy. For example, it has been shown that in 2016/17, 89% of new or variation applications in CIP areas have still been granted, which may suggest a limited impact [10]. However, some areas, such as Newcastle, have seen use of CIPs inhibit growth of the off-trade [11], where they are recognised as a useful ‘place shaping’ tool, enabling local authorities to encourage best practice, and to positively influence the development of the licensed trade in ways less likely to have a negative local impact. In 2015, the Conservative Government pledged to put CIPs on a statutory footing in their Modern Crime Prevention Strategy [12], and these came into effect in through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 [13]. It should be noted, that the use of policies such as CIPs are limited by competition law [14].

Price and pre-loading

Evidence from both natural experiments and modelling studies support a link between alcohol pricing and overall crime.

More specific to the night-time economy, there is considerable concern over heavily discounted sales of alcohol at off-licences as the source of a recent phenomenon known as ‘pre-loading’. The act of pre-loading involves groups of drinkers consuming alcohol – purchased from off-licences – in private settings prior to attending nightlife venues.

The evidence

Increases in tax/price have been demonstrated to be associated with reductions in overall crime and decreases in tax/price with an increase in overall crime [15]. One study examining the influence of the price of beer on injuries suffered in England and Wales suggested that increased alcohol prices would result in substantially fewer violent injuries [16]. A meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of various alcohol price policies found that doubling alcohol tax would reduce crime by 1.4% and violence by 2% [17]. Similar findings have been identified in Canada, where a 10% increase in provincial minimum alcohol prices was associated with a 9.17% reduction in crimes against persons and an 18.81% reduction in alcohol-related traffic violations [18].

International evidence examining 16 countries has also suggested a link between prices increases and lower levels of crime; a 1% price increase was found to be associated with decreases is the likelihood of robbery, assault, and sexual assault (0.19%, 0.25%, and 0.16% respectively) [19].

The Home Office also acknowledged the relationship between price and harm in its review of the research literature:

When considering individual crime types rather than overall crime, there is a larger evidence base for a link between alcohol price and violence than for other crime types. The balance of this evidence tends to support an association between increasing alcohol price and decreasing levels of violence [20].

Decreases in price of alcohol have been linked to increased rates of domestic violence. US research has found that price increases meant wives were less likely to experience ‘severe’ violence [21], while the risk of wives experiencing domestic abuse decreased by 5% with a 1% price increase [22].

With regard to pre-loading, one survey of 18–35-year-olds in the North West region of England found that those who engaged in this practice reported significantly higher total alcohol consumption over a night out than those who waited to drink until reaching the bars and nightclubs. Pre-loaders were also more than twice as likely to have been involved in a fight. The researchers concluded that measures to reduce drunkenness and alcohol-related violence in the night time economy should not be restricted to premises within the nightlife environment but should also tackle disparities in pricing and policing between on and off-licences [23].

Solutions

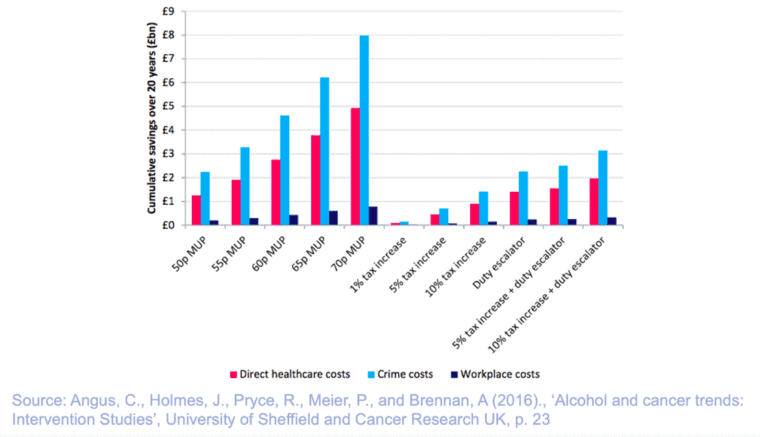

Research released in 2016 from Cardiff University estimates* that a 1% increase in on- and off-trade prices above inflation in England and Wales could avoid more than 6,000 violence-related emergency department attendances every year [24]. In the face of such evidence, minimum unit pricing (MUP) presents itself as one such policy tool designed among other things to reduce the level of crime and social disorder. Modelling published by the University of Sheffield and Cancer Research UK in 2016 suggests a 50p MUP would lead to a 2.4% fall in alcohol-related crime, saving the criminal justice system £2.2 billion in 20 years [25]. The effect on crime costs of implementing MUP at a variety of levels was modelled and is presented in figure 1 (below) [26].

Figure 1 Estimated savings in costs to society (£bn) in England 2015–2035,

under alternative pricing policies

In response to such evidence, Scotland attempted to implement MUP, passing the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act in June 2012. However, due to a legal challenge led by the Scotch Whisky Association, its implementation was delayed for six years [27]. The measure was deemed legal by the UK Supreme Court in 2017 [28] and finally enacted on 1 May 2018 [29]. In Wales, the government passed legislation for MUP in June 2018 [30] and the Republic of Ireland did the same in October of that year [31]. The Northern Ireland Government has the powers to introduce MUP, and the previous administration expressed its intention to do so [32].

While England has not implemented MUP, there has been a ban on businesses selling alcohol below the cost of duty plus VAT here since 2014 [33]. However, whilst this may appear a positive step, it has been demonstrated that this strategy would have little substantive impact, and that MUP approaches would be more effective in reducing excessive consumption [34,35]. **

Vertical drinking establishments and high risk premises

Other features of the night time economy have also been identified as causes of excessive or otherwise problematic consumption – in particular, the presence of youth orientated ‘vertical drinking’ establishments where drinking is an end in itself rather than an accompaniment to other activities such as having a meal while seated at a table or watching live music.

The evidence

Specific factors have been linked to a higher likelihood of aggression in public drinking settings, including [36,37,38]:

- crowding, poor bar layout and traffic flow

- inadequate seating or inconvenient bar access

- dim lighting, noise, poor ventilation or unclean conditions

- discount drinks and promotions that encourage heavy drinking (e.g. ‘happy hours’)

- lack of availability of food

- a ‘permissive’ environment that turns a blind eye to anti-social behaviour

- punters with a history of aggression and who binge drink

- bar workers who don’t practice responsible serving (or who are poorly trained)

- aggression/intimidation by security staff

- poor access to late night transport

- prominent alcohol promotion

- aggressive content in music

- a ‘rowdy atmosphere’

Solutions

In Canada, the Safer Bars training programme has shown success in reducing aggression by developing staff skills in managing and reducing aggressive behaviour. A randomised trial showed that the programme reduced severe and moderate aggression in intervention premises; these effects were moderated by the turnover of managers and door staff in bars, with higher staff turnover associated with higher aggression post-intervention [39].

In the UK, the Home Office has produced a summary of the various strategies available to owners/managers of licensed premises to help reduce violence in and around their businesses, including a set of interventions on the layout and management of bars and clubs as alcohol vendor venues in the night time economy (see figure 2).

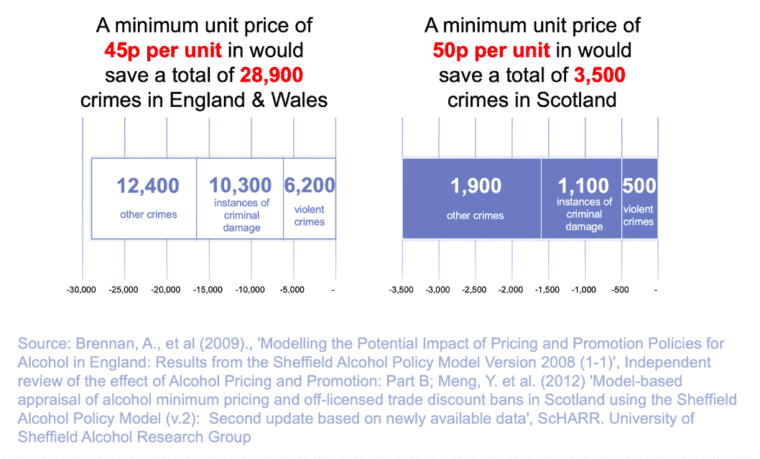

Figure 2 Estimated effects of MUP on crimes committed, England & Wales and Scotland

The licensed trade often champion voluntary schemes as effective at reducing crime and disorder. While these can be effective in some instances, they are often poorly evidenced and appear to be better at encouraging best practice and information sharing as opposed to significantly impacting on crime and disorder [40].

Increasing temporal availability

As with physical availability, it has been suggested that increased temporal availability may serve to increase rates of alcohol-related crime. The Alcohol Health Alliance UK, University of Stirling, and British Liver Trust have collectively raised the sharp increases in temporal availability of alcohol seen in recent decades:

Alcoholic drinks are no longer bought in specific places and at specific times for specific drinking routines. They can be bought anywhere, at any time, as part of the routine of daily life. This has eroded the public perception that these are distinctive, and above all harmful, products [41].

A core premise of the Labour Government’s licensing reforms was that binge drinking was largely the result of artificially early closing times, which encouraged rapid consumption of alcohol in order to ‘beat the clock’. The proposed solution was to extend drinking hours so as to encourage more leisurely consumption. The expectation was that, provided with longer drinking hours, customers would not drink any more alcohol but that they would drink the same amount more slowly, thus reducing levels of drunkenness. However, survey data suggest that, contrary to the assumption underlying the Licensing Act 2003, prolonged stays in premises with extended drinking hours actually result in higher levels of reported consumption [42]. ***

The evidence

Evidence from Australia suggests restricted trading hours could limit alcohol-related violence. In recent years, two regions have introduced ‘last drinks’ policies: in New South Wales (NSW), including from 3.30am in the city of Newcastle, from 3am in Sydney’s CBD, and from 10pm for all takeaway alcohol across the region; and from 2am in Queensland, ‘with venues inside zoned “Safe Night Precincts” permitted to trade until 3am’ [43].

Multiple evaluations of the NSW intervention observed reductions in harm, with one concluding the measures ‘appear to have reduced the incidence of assault in the Kings Cross and CBD entertainment precincts.’ Reduced alcohol consumption appears central to this, as the reduction in non-domestic assaults was larger than the reduction in foot traffic in the region; reductions of 45.1% and 19.4% respectively. The policies were also found to bring further benefits wider than violence reductions, including a 60% reduction in serious facial injuries requiring surgery in the two years after the policy was introduced [44].

Solutions

The Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 gave local agencies a set of powers which would enable them to counter the most damaging effects of the Licensing Act, most notably flexible opening hours for licensed premises, including Late Night Levies and Early Morning Restriction Orders (EMRO). These allow local authorities to target specific trouble zones in the night time economy in an attempt to stop crime and social disorder occurring into the early hours of the morning [45].

Late night levies are levies on licensed premises open into late hours intended to fund, amongst other things, increased police activity to address alcohol-related crime. Such schemes have been implemented in some locations, with varying success – Cheltenham for example cancelled their scheme after it only raised a portion of the projected funds [46], whilst Newcastle did meet the projected revenue from the scheme [47]. In London, Islington used funding generated by the scheme to increased police street presence. Changes to the LNLs through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 have seen the measures become more flexible for authorities. These can now be introduced to more discrete regions – a street, as opposed to a whole local authority area – as well as for venues selling late-night refreshment such as takeaways [48]. However, there is yet to be a formal evaluation into their impact.****

Other initiatives

Transport policies

Some policies relate specifically to alcohol-related crime and social disorder on public transport. For example, in London, an alcohol ban was introduced on all Transport for London (TfL) services from 1 June 2008 by Mayor Boris Johnson, under the claim that it would reduce crime in the capital [49]. The ban has so far proved popular with commuters; research carried out by the Greater London Authority found that 87% of Londoners were in support. It is also said to have had a significant influence on the 15% fall in the number of assaults on Tube staff between 2008 and 2011 [50].

In 2016, TfL introduced a 24-hour weekend period service on some tube lines. With the introduction of this service, TfL themselves have projected an increase in alcohol-related incidents at end of line stations [51]. Indeed, in response to their experience of policing the network to date, British Transport Police recently warned of dangers to intoxicated lone travellers from sexual predators who might exploit their vulnerability whilst using the service, and that personal safety risks taken by intoxicated persons could cause serious injuries to themselves and others [52,53]

Anonymous data sharing: the Cardiff Model

Research has shown that the dissemination of information via the emergency services is key when dealing with social problems, crime and violent assault. The College of Emergency Medicine has produced guidance, which is based on the ‘Cardiff model for Violence Prevention’, that sets out the importance of sharing non-personal data with the police, particularly core information on the date, location and type of assault.

Findings from a study conducted by the University of Cardiff highlight the important role of senior clinical, police and local authority leadership in promoting active use of the intelligence to target policing and tackle problem premises [54]. Data sharing and local advocacy on the part of trauma surgeons has prompted the formation of local police task forces responsible for targeting city street crime, and overt and covert police interventions, targeted at violence hotspots such as particular licensed premises, and the use of injury data to oppose drinks/entertainment licence applications by the alcohol industry [55].

Implementation of these measures in Cardiff has been followed by:

- an overall decrease of 35% in numbers of assault patients seeking Emergency Department (ED) treatment (2000–5), compared with an overall 18% decrease in England and Wales over the same period

- a 31% decrease in assaults inside licensed premises in Cardiff city centre (1999–2001)

- lower levels of violence than all [but 4 of the] 55 towns and cities in England and Wales with a population greater than 100,000 (by 2005)

In its Home Office ‘family’ of 15 similar cities (based on socio-economic and demographic variables) the Welsh capital was safest of the group for 3 years (2003–6). On the basis of such evidence, the Coalition Government encouraged all hospitals to share non-confidential information on alcohol-related injuries with the police, by granting licensing and local health bodies the status of ‘responsible authorities’ under the Licensing Act 2003 [56].

In line with this, the government have highlighted the role of information sharing in tackling alcohol-related crime in their Modern Crime Prevention Strategy. They emphasise the need to improve local intelligence, in order to make evidence based decisions about ‘the sale of alcohol and the management of the evening and night time economy’, and that they ‘expect more local NHS trusts to share information about alcohol-related violence to support licensing decisions taken by local authorities and the police, adopting the success of the Cardiff Model’ [57].

Alcohol Treatment Requirement (ATR)

ATRs may be imposed either as part of a community sentence of up to three years, or attached to a suspended sentence order of up to two years, to offenders who present serious problems with alcohol and where it is identified as a significant factor in the person’s offending. Once an ATR order is issued by the courts, the individual must agree to a treatment plan with probation and the treatment provider. S/he will have access to a tailored treatment programme with the aim of reducing or eliminating alcohol dependency. This requires a high level of intervention, including prescribed treatment including detoxification, one-to-one contact or interventions, care planned counselling and assistance to obtain Residential Rehab subject to Community Care funding and general waiting lists. Breaching an ATR will result in a return to court for more onerous conditions to be applied, or a substituted prison term. The completion rate for ATRs remained relatively stable between 2009/10 and 2013/14, at around 70% [58].

However, some have suggested that treatment under coercive conditions might have limited effectiveness. A review examining this found that ‘three decades of research into the effectiveness of compulsory treatment have yielded a mixed, inconsistent, and inconclusive pattern of results, calling into question the evidence-based claims made by numerous researchers that compulsory treatment is effective in the rehabilitation of substance users’. [59]

Alcohol Arrest Referral (AAR)

In England, an Alcohol Arrest Referral (AAR) trial run began in 2007. These were piloted in four constabularies, before being phased in across eight others the following year. AAR involves offering a brief intervention to individuals arrested and deemed by a police officer to be under the influence of alcohol and typically involves a brief intervention session with an AAR worker, with a view to ‘follow-up’ sessions in some cases. A Home Office evaluation report on the AAR scheme, published shortly before the 2012 Alcohol Strategy, concluded that there was no strong evidence to suggest that AAR had a criminal justice impact in terms of reducing re-arrest, although there was some limited evidence of reduced alcohol consumption among the intervention groups [60].

Criminal Behaviour Order and the Public Space Protection Order

These orders both emerged following a streamlining of the categorisation of orders available to courts when sentencing offenders enacted through the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 [61].

- Public Space Protection Orders (PSPOs – previously DPPOs)

In England, provisions for dealing with alcohol-related crime disorder were created in the Police & Criminal Justice Act 2001 [62]. These permitted the introduction of Designated Public Place Orders (DPPOs) at a local authority level. These have now been replaced by PSPOs under the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014. PSPOs ban specific acts in a designated geographical area, such as the consumption of alcohol. Existing DPPOs were converted to PSPOs in October 2017 [63].

- Criminal Behaviour Order (CBO) / Drink Banning Order (DBO)

CBOs can be assigned by criminal courts on conviction for any criminal offence, and are designed to tackle serious antisocial behaviour, including that relating to alcohol such as persistently being drunk and aggressive in public [64]. DBOs came into force in August 2009 and were replaced by CBOs in 2014. They can last for any specified period of time between two months and two years. Offenders who breach a DBO are liable to pay a penalty of up to £2,500 [65]. After 20th October 2019, any existing DBOs will be considered CBOs [66].

Sobriety tagging

This scheme aims to reduce alcohol-related crime by fitting binge drinkers who commit a defined set of alcohol-related crimes with monitors that assess their sobriety. Following a successful trial in London (with a 92% compliance rate) [67] the scheme will be rolled out nationwide [68]. Treatment and advice is also available to participants; a factor charity Alcohol Concern has emphasised as key [69].

However, it has also been noted that there are some crime types for which such a scheme would be unsuitable. For example, the Institute of Alcohol Studies questioned the application of such a scheme to domestic violence offences, noting that even where perpetrators comply with such schemes, a tagging scheme used in isolation will not necessarily generate long-lasting attitude or behaviour changes, and may inadvertently continue to leave victims to abuse [70].

‘The Alcohol Fund’ project

This £1 million project identified 10 key areas to support to address alcohol-related problems. A variety of strategies across the areas where employed, and some regions saw reduction in alcohol-related crime [71]. It will be important to see the sustainability of these outcomes longer term.

* The authors of this study suggest that taxation may be a more effective strategy than minimum unit pricing (MUP) for reducing such violence-related injury. However, they do not provide evidence to support this, and this study did not model the potential impact of MUP – taxation’s effectiveness was proposed by the authors. This study focused on the on-trade which may account for this suggestion, as off-trade prices would be affected more by MUP, whereas on-trade prices are more likely to impacted by rises in taxation.

** Please consult the Price factsheet for more information

*** Please consult the Licensing factsheet for more information

**** More on licensing solutions can be found in the Licensing factsheet

- Alcohol Focus Scotland and CRESH. 2018. Alcohol Outlet Availability and Harm in Scotland, p. 8

- Warburton, A. L., and Shepherd, J. P. 2004. An evaluation of the effectiveness of new policies designed to prevent and manage violence through an interagency approach. Welsh Assembly Government, Wales Office of Research and Development.

- Newberry, M., Williams, N. and Caulfield, L., 2013. Female alcohol consumption, motivations for aggression and aggressive incidents in licensed premises. Addictive behaviors, 38(3), pp. 1844–1851

- Stewart, K. 2005. How Alcohol Outlets Affect Neighborhood Violence. Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research Evaluation, pp. 2–3

- Stewart, K. 2005. How Alcohol Outlets Affect Neighborhood Violence. Prevention Research Center, Pacific Institute for Research Evaluation, p. 3

- Hobbs, D. 2003. Bouncers: Violence and governance in the night-time economy. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Alcohol Change UK. 2012. Full to the brim? Outlet density and alcohol-related harm, p. 3

- The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and The Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2017. Anytime, anyplace, anywhere? Addressing physical availability of alcohol in Australia and the UK, p. 39

- Foster, J., and Charalambides, L. 2016. The Licensing Act (2003): its uses and abuses 10 years on. The Institute of Alcohol Studies. p. 193

- Home Office. 2017. Alcohol and late night refreshment in England and Wales 31 March 2017, data tables, Table 6

- The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and The Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2017. Anytime, anyplace, anywhere? Addressing physical availability of alcohol in Australia and the UK, p. 31

- HM Government. 2016. Modern Crime Prevention Strategy, p. 36

- House of Commons Library. 2017. Briefing paper no. 07269. Alcohol: cumulative impact assessments, p. 3

- The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and The Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2017. Anytime, anyplace, anywhere? Addressing physical availability of alcohol in Australia and the UK, p. 39

- Booth A., et al. 2010. Alcohol pricing and criminal harm: a rapid evidence assessment of the published research literature. ScHARR, University of Sheffield, p. 14

- Matthews, K., Shepherd, J. and Sivarajasingham, V. 2006. Violence-related injury and the price of beer in England and Wales. Applied Economics, 38(6), pp. 661–670

- Wagenaar, A.C., Tobler, A.L. and Komro, K.A., 2010. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), p. 2,270

- Stockwell, T., Zhao, J., Marzell, M., Gruenewald, P.J., Macdonald, S., Ponicki, W. R. and Martin, G. 2015. Relationships between minimum alcohol pricing and crime during the partial privatization of a Canadian government alcohol monopoly. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(4), p. 634

- Markowitz. S. 2000. Criminal Violence and Alcohol Beverage Control: Evidence from an International Study. Working paper No. 7,481, published in ‘The Economic Analysis of Substance Use and Abuse: The Experience of Developed Countries and Lessons for Developing Countries,” edited by Michael Grossman and Chee-Ruey Hsieh, Edward Elgar Limited, United Kingdom, 2001’. Accessed from the National Bureau of Economic Research. p. 18

- Secretary of State for the Home Department. 2011. The likely impacts of increasing alcohol price: a summary review of the evidence base. HM Government. p. 4

- Markowitz. S. 2000. The Price of Alcohol, Wife Abuse, and Husband Abuse. Southern Economic Journal, Volume 67, Issue 2, accessed from the National Bureau of Economic Research. p. 20

- Patra, J., Giesbrecht, N., Rehm, J., Bekmuradov, D. and Popova, S. 2012. Are alcohol prices and taxes an evidence-based approach to reducing alcohol-related harm and promoting public health and safety? A literature review. Contemporary Drug Problems, 39(1), pp. 7–48

- Hughes, K., Anderson, Z., Morleo, M. and Bellis, M. A. 2008. Alcohol, nightlife and violence: the relative contributions of drinking before and during nights out to negative health and criminal justice outcomes. Addiction, 103(1), pp. 60–65

- Page, N., Sivarajasingam, V., Matthews, K., Heravi, S., Morgan, P. and Shepherd, J. 2017. Preventing violence-related injuries in England and Wales: a panel study examining the impact of on-trade and off-trade alcohol prices. Injury prevention, 23(1), p. 39

- Angus, C., Holmes, J., Pryce, R., Meier, P. & Brennan, A. 2016. Alcohol and cancer trends: Intervention Studies. University of Sheffield and Cancer Research UK, p. 28

- Angus, C., Holmes, J., Pryce, R., Meier, P. & Brennan, A. 2016. Alcohol and cancer trends: Intervention Studies. University of Sheffield and Cancer Research UK, p. 23

- Alcohol Health Alliance. 2017. Minimum unit pricing ruled legal

- Alcohol Policy UK. 2017. Minimum unit pricing to go ahead in Scotland after 5 year legal battle

- Scottish Government. 2018. Minimum Unit Pricing

- Drink and Drug News. 2018. Minimum pricing law passed in Wales.

- Alcohol Action Ireland. 2018. Minimum Pricing

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2015. Northern Ireland to proceed with Alcohol Minimum Unit Pricing

- Secretary of State for the Home Department. 2014. Guidance on banning the sale of alcohol below the cost of duty plus VAT, p. 3

- Leicester, A. 2011. Alcohol pricing and taxation policies. Institute for Fiscal Studies, p. 3

- HM Government. 2012. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy. p. 7

- The Portman Group, 1998. Keeping the Peace: A Guide to the Prevention of Alcohol-Related Disorder, revised edition

- Graham, K. and Homel, R., 2008. Raising the bar: Preventing aggression in and around bars, clubs and pubs. UK: Willan Publishing, London.

- McFadden, A.J., Young, M. and Markham, F. 2015. Venue-level predictors of alcohol-related violence: An exploratory study in Melbourne, Australia. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(4), p. 506

- Graham, K., Osgood, D. W., Zibrowski, E., Purcell, J., Gliksman, L., Leonard, K., Pernanen, K., Saltz, R. F. and Toomey, T. L. 2004. The effect of the Safer Bars programme on physical aggression in bars: results of a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(1), pp. 31–41

- Foster, J., and Charalambides, L. 2016. The Licensing Act (2003): its uses and abuses 10 years on. The Institute of Alcohol Studies

- University of Stirling, Alcohol Health Alliance, and British Liver Trust. 2013. Health First: An evidence-based alcohol strategy for the UK, p. 30

- Green, C., Hollingsworth, B., and Navarro, M. 2016. Longer opening hours lead to heavier drinking and severe health damage.

- The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and The Institute of Alcohol Studies, p. 10.

- Ibid. p. 16

- Ibid. p. 26

- The Publican’s Morning Advertiser. 2016. Cheltenham late-night levy to be scrapped after scheme flops

- The Publican’s Morning Advertiser. 2015. Newcastle councils raises £300k from late night levy.

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2018. IAS response to Night Time Commission Consultation Submission, p. 10

- BBC News. 2008. Johnson bans drink on transport

- London.gov.uk. 2011. Londoners continue to back Mayor’s booze ban

- The Huffington Post. 2016. Night Tube: The 12 Underground Stations Where Crime May Increase Revealed By London Assembly

- Simpson, F. 2018. Don’t fall asleep on the Night Tube: police chief’s warning to lone travellers

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2018. IAS response to Night Time Commission Consultation Submission, p. 1

- HM Government. 2012. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy. p. 15

- Shepherd, J. 2007. Preventing violence – caring for victims. Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Surgeon, 5: 2, p. 116

- HM Government. 2012. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy. pp. 11–14

- HM Government. 2016. Modern Crime Prevention Strategy, p. 34

- Ministry of Justice. 2015. National Offender Management Service Annual Report 2014/15: Management Information Addendum, p. 21

- Klag, S., O’Callaghan, F. and Creed, P. 2005. The use of legal coercion in the treatment of substance abusers: An overview and critical analysis of thirty years of research. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(12), p. 1,777

- Home Office. 2012. Summary of findings from two evaluations of Home Office Alcohol Arrest Referral pilot schemes

- Secretary of State for the Home Department. 2014. Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, Chapter 12. HM Government, House of Commons

- Secretary of State for the Home Department. 2001. Chapter 2: Provisions for combatting alcohol-related disorder. Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 c. 16. HM Government, House of Commons

- Eden District Council. n.d. Public Spaces Protection Order

- Sentencing Council. n.d. 5. Criminal behaviour orders

- Alcohol Policy UK. 2009. Drinking banning orders come into force

- The Crown Prosecution Service. n.d. Criminal Behaviour Orders

- London.gov.uk. 2016. ‘Sobriety tags’ rolled out across London

- HM Government. 2016. Modern Crime Prevention Strategy, p. 36

- Alcohol Policy UK. August 2015. Alcohol offender ‘sobriety tag’ scheme could go national

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. 2018. Transforming the response to domestic abuse – consultation response, pp. 26–27

- Department for Communities and Local Government. 2015. The Alcohol Fund End of project

View this report