View this report

Summary

- Drunk airline passengers can be disruptive to other travellers and, in the worst instances, a safety threat

- 60% of adult Brits who have travelled by air have encountered drunk passengers and a majority (51%) believe there is a serious problem with excessive alcohol consumption during air travel.

- Alcohol sales in airports and management of drunk passengers take place within a framework underpinned by mix of international legislation and agreements, UK legislation and voluntary codes of practice.

- In England and Wales, airside alcohol sales are not governed by the Licensing Act 2003, meaning that alcohol sales are not subject to the same conditions as elsewhere.

- Following recommendations for reform from a House of Lords Select Committee on the Licensing Act, the Government carried out a call for evidence on this issue concluding in February 2019. A government response to the call for evidence has not yet been published.

Introduction

There has been increased focus on the problems caused by drunk, disruptive passengers in recent years in the media and amongst UK parliamentarians. Surveys have found most passengers on flights believe that it is a serious problem, and there are high levels of public support for expanding licensing restrictions airside.

This briefing covers the extent of the problem, and what measures have been put in place to tackle it.

The size of the problem

Though drunk and disruptive passengers make up a small percentage of total passengers, their impact is disproportionate. Mid-air, disruptive passengers can constitute a threat to the safety of other passengers and crew and be unpleasant and scary for those onboard, including children. A survey of 4,000 cabin crew members by Unite the Union found that the overwhelming majority of crew had witnessed drunk, disruptive passenger behaviour and over half of cabin crew had experienced or witnessed physical, verbal or sexual abuse at the hands of drunken passengers [1]. Drunk, disruptive passenger incidents can also cause significant costs and disruption, in the worst cases incidents result in the diversion of flights, estimated to typically cost between £10,000 – £80,000. According to the Civil Aviation Authority, disruptive passenger behaviour is one of the main reasons for aircraft diversions [2].

There has been increased focus on the problems caused by drunk, disruptive passengers in recent years in the media and amongst UK parliamentarians. Globally there were over 66,000 incidents reported to IATA, the international representative body for airlines, between 2007 – 2017 [3]. In 2017, 8,713 unruly passenger incidents were reported, equalling one incident per 1,053 flights, with intoxication and consuming own alcohol the second most common reason for an unruly passenger incident. IATA’s figures show all unruly passenger incidents (including those unrelated to alcohol) rose up to a peak in 2015, followed by small reductions in 2016 and 2017, the most recent year reported [4].

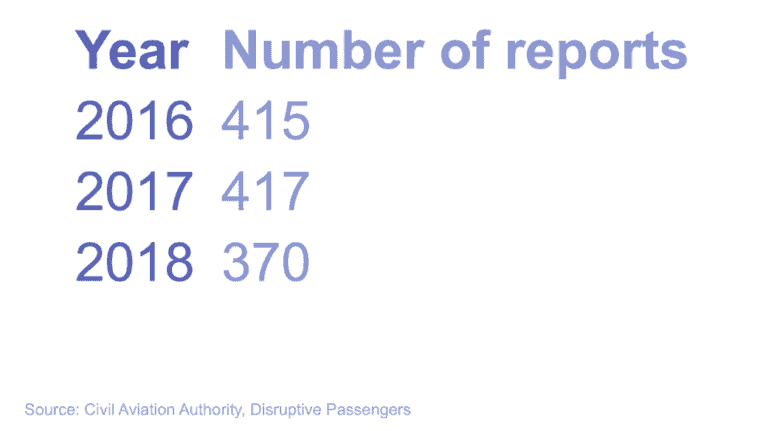

The Civil Aviation Authority, the UK’s aviation regulator, publishes figures for incidents involving disruptive passengers reported in the UK. They note an 100% increase in occurrences between 2015 and 2016, with the figures for the most recent years as follows:

Figure 1: Annual incidents of disruptive passengers reported to the Civil Aviation Authority, 2016-2018

These give some indication of the scale of the problem however, there are challenges in drawing comparisons between years. The increase in reports between 2015 and 2016 is at least in part due to a change in reporting requirements in 2016 and the reduction in the 2018 figure is largely due to reductions in the numbers of commercial aircraft on the register [5]. Furthermore, though there is a requirement to report certain incidents, only the most serious cases of disruption are reported to the CAA, meaning that more minor incidents are not captured.

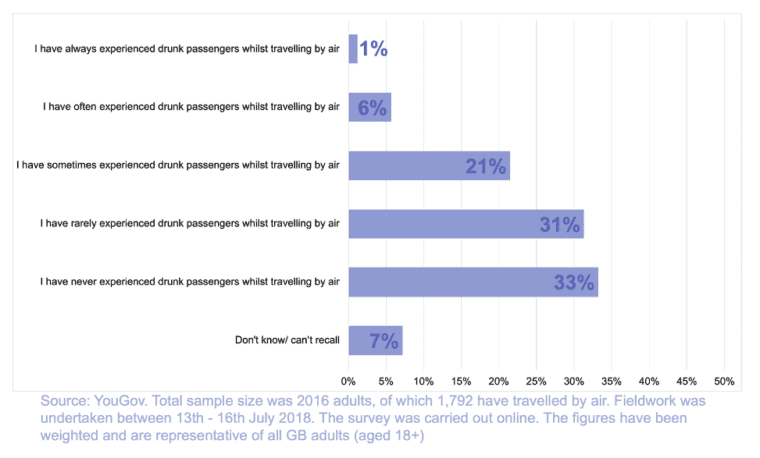

Public opinion polling indicates this is a significant issue for travellers. A YouGov survey carried out for the Institute of Alcohol Studies in 2018 found that 60% of British adults who had travelled by air had encountered drunk passengers with a majority (51%) believing there is a serious problem with excessive alcohol consumption during air travel [6].

Figure 2: YouGov survey question: How often, if at all, have you experienced drunk passengers whilst travelling by plane (ie either in an airport or whilst on your flight)?

In 2020, the aviation industry was significantly impacted by COVID-19, with many flights cancelled during the year and the demand for air travel down on previous years. There were reports over the summer that some airlines suspended sales of alcoholic drinks onboard their flights in response to COVID-19 [7]. Further evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on disruptive passengers will emerge in future.

Pre-flight alcohol consumption

Drinking which leads to disruptive in-flight behaviour may begin on the flight itself, in the airport – either alcohol bought at bars and restaurants or in duty-free – or even before arrival at the airport. Pre-flight drinking creates difficulties for cabin crew in monitoring passengers’ consumption.

The Licensing Act 2003 doesn’t apply beyond security in airports in England and Wales due to an exemption which dates back several decades. This has a significant impact on the drinking environment in airports with drinks sold in places that would not normally stock alcohol, and alcohol sold at a wider range of hours [8]. A House of Lords Committee looking into the issue noted ‘no one travelling on an international flight can fail to notice that, once they have gone through customs, control of the sale of alcohol seems to be relaxed, and the permitted hours even more so’ [9]. The Committee also received evidence from police about alcohol sales to under 18s that they were unable to take action on due to the Licensing Act offences not applying airside [10].

Air travel is linear by its nature. A typical journey by air might look like this:

This presents a challenge for airport and airline staff as passengers may spend only a short time in each stage and the effects of alcohol consumption can take time to become evident, making it difficult for staff to judge whether a person is too intoxicated to board a flight. There are efforts by aviation stakeholders to work together to address the problem and act holistically – for example Glasgow airport’s campus watch scheme that includes information campaigns, and an information exchange mechanism between airport staff such as police, retail and bar staff for identification of potentially disruptive passengers.

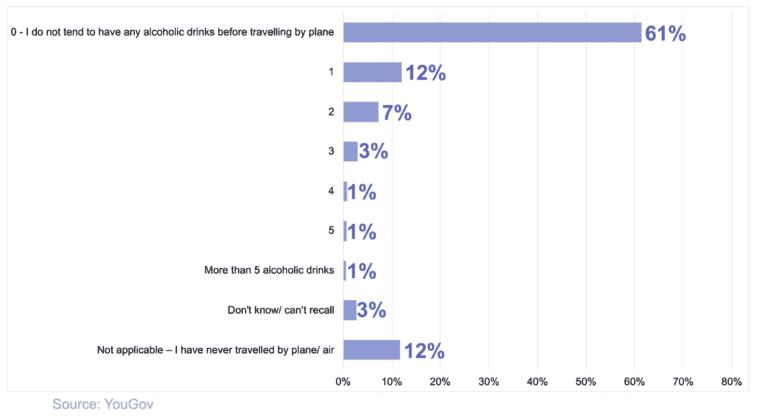

Despite the disproportionate problems caused by drunk, disruptive passengers, it is clear that drinking during air travel is undertaken by a minority of people. A YouGov survey for IAS showed that only 24% of Adult Brits reported drinking alcohol in airports, with only 2% of adults reporting drinking four drinks or more [11].

Figure 3: On average, how many alcoholic drinks, if any, would you say you tend to have before you travel by plane (ie at the airport)?

Voluntary agreements

There are some voluntary agreements and codes which cover this area including:

- The One Too Many campaign launched in 2018 as a collaboration between aviation stakeholders including the Airline Operators Association, Airlines UK, the UK Travel Retail Forum and IATA. The campaign seeks to raise awareness of the consequences of disruptive behaviour [12].

- The UK Aviation Industry Code of Practice created in 2016 by retailers, police and airlines, and supported by the UK Government. The code sets out guidelines for preventing disruptive behaviour through the responsible sale of alcohol, training and support for employees and communication with passengers. It allows for identification and management of potentially disruptive passengers [13].

- The 2015 Duty Free World Council Self-Regulatory Code of Conduct for the Sale of Alcohol Products in Duty Free & Travel Retail. This requires alcohol promotions at airports not to encourage excessive consumption, gives guidance on refusing sale of alcohol to those who are intoxicated [14].

The legal framework

EU regulation, which applied to the UK until the end of the EU exit transition period, states that airlines shall ‘take all reasonable measures to ensure that no person enters or is in an aircraft when under the influence of alcohol or drugs to the extent that the safety of the aircraft or its occupants is likely to be endangered’. It also prohibits crew members and commanders from carrying out duties when under the influence of alcohol [15].

Airlines do develop and enforce their own boarding and service policies and some airlines use their own policies within the existing legislative framework to reduce and deter drunk, disruptive passengers. For example, Ryanair initiate civil action against disruptive passengers as a deterrent. On certain routes they send emails in advance of flights to warn about disruptive behaviour, and separate passengers from alcohol they’ve bought in duty-free at the boarding gate [16].

The Montreal protocol (known as MP14) came into force in January 2020. This allows the police in the landing airport to prosecute disruptive passengers. MP14 is an important and positive development as previously passengers who were involved in mid-air disruption could have escaped prosecution as it was police forces in the jurisdiction where the aircraft was registered which had responsibility for prosecution. It was estimated that prior to MP14 about 60% of offences went unpunished due to jurisdictional issues [17]. The protocol will empower police to prosecute all cases of passenger disruption, not only those associated with alcohol.

In the UK there is a maximum sentence of two years in prison or a fine of £5,000 for drunkenness on an aircraft, with the maximum sentence increasing to five years in cases where the safety of aircraft or passengers has been put at risk. In addition to the fine, passengers can be made to pay the costs of diversion, which can be up to £80,000 [18].

The House of Lords Committee conducting post-legislative scrutiny on the Licensing Act 2003 recommended that the Licensing Act should apply airside as it does in the rest of the airport [19]. Concerns have been raised about practical issues relating to the application of the Licensing Act airside such as the difficulty of licensing officers carrying out inspections in the secure area. However, the House of Lords Committee noted ‘we are not for one moment persuaded by this view’, pointing out the licensing enforcement officers could receive security clearance to allow them to carry out their duties.

There are high levels of public support for extending the Licensing Act airside, with 86% of Adult Brits who travelled by air supporting the proposal compared with only 4% who opposed it [20].

The UK Government acting for England and Wales responded to the House of Lords Committee’s recommendation by issuing a call for evidence on the issue at the end of 2018 [21]. Proposals have not yet been published following the conclusion of the call for evidence.

- Unite the Union cabin crew survey, cited in Institute of Alcohol Studies and Eurocare (2018) Fit to Fly: Summary Report of the Policy Debate on Alcohol and Air Travel

- Civil Aviation Authority, Disruptive Passengers

- IATA Unruly Passengers

- IATA (2017) Unruly and Disruptive Passenger Incidents

- Civil Aviation Authority, Disruptive Passengers

- YouGov. Total sample size was 2016 adults, of which 1,792 have travelled by air. Fieldwork was undertaken between 13th – 16th July 2018. The survey was carried out online. The figures have been weighted and are representative of all GB adults (aged 18+)

- CNN Travel Airlines ban alcohol on planes in response to COVID-19

- Institute of Alcohol Studies and Eurocare (2018) Fit to Fly: Summary Report of the Policy Debate on Alcohol and Air Travel

- House of Lords Select Committee on the Licensing Act 2003 (2017) The Licensing Act 2003: Post-legislative Scrutiny

- Ibid

- YouGov survey, op cit

- One Too Many website

- BATA, ALMR, UK Airport Police Commanders, AOA, UK Travel Retail Forum, Travel Retail (2016) The UK Aviation Industry Code of Practice on Disruptive Passengers

- Duty Free World Council (2015) Self-Regulatory Code of Conduct for the Sale of Alcohol Products in Duty Free & Travel Retail

- European Commission (2014) Commission Regulation (EU) No 379/2014

- Institute of Alcohol Studies and Eurocare (2018) Fit to Fly: Summary Report of the Policy Debate on Alcohol and Air Travel

- IATA (2019) Boost for Efforts to Tackle Unruly Passengers as MP14 Set to Come into Force

- Civil Aviation Authority, Disruptive passengers

- House of Lords Select Committee on the Licensing Act 2003 (2017) The Licensing Act 2003: Post-legislative Scrutiny

- YouGov, op cit

- Home Office (2018) Airside alcohol licensing at international airports in England and Wales: call for evidence

View this report