View this report

Summary

- The heaviest drinkers, and thus those with the greatest likelihood of experiencing alcohol problems, tend to be concentrated in those of working age

- Long working hours, high physical demand and risk of injury, job insecurity and fitting in to the organisation culture are some of the factors relating to the workplace which influence a person’s level of alcohol consumption

- However, drinking during working hours or attending work hungover can impact productivity negatively, and runs a higher risk of an employee being disciplined for various kinds of misconduct

- If problem drinking persists, it can lead to a range of social, psychological and medical problems for an employee, including dependence

- Many organisations now operate workplace alcohol policies designed to ensure that employees are sober during working hours and to identify and help employees with that require support

Introduction

Official statistics show that employed people are more likely to drink heavily than unemployed people [1], and that the proportion of workers drinking excessively is highest in managerial and professional occupations, where about a third of staff (36% in 2017) report heavy drinking [2].

The effects of alcohol misuse in the workplace invariably have harmful implications on the health and social behaviour of employees and employers in the workplace; an Impact Assessment paper on minimum pricing calculated lost productivity due to alcohol in the UK (including premature death of working age people, unemployment, and sickness absence) at about £7.3bn per year (at 2009–10 prices) [3].

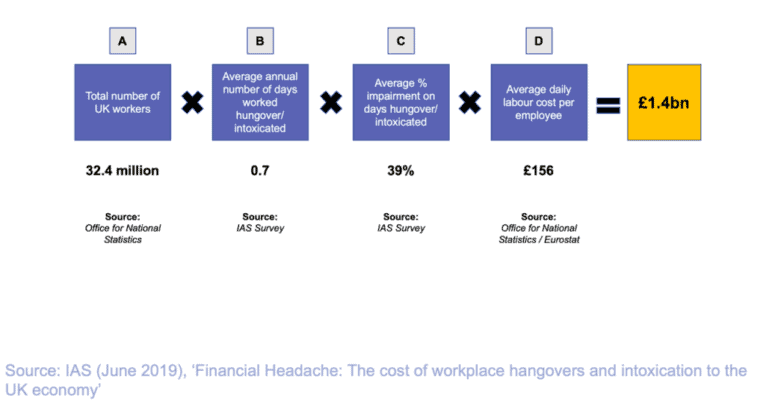

More recently, an IAS report calculated the cost of workplace hangovers to the UK economy at £1.2bn to £1.4 bn a year [4].

However, despite the noted high costs of alcohol-related harms to businesses, some employers continue to tolerate or even encourage drinking at several stages of working life among staff, from first initiation with colleagues and as a element of socialising through to rewarding individual or group achievements. Employers have a duty of care to promote health and wellbeing among their staff, and should be mindful that some workers use alcohol as a coping mechanism for managing the pressures of modern life.

This briefing addresses these concerns and their causes, examines the underlying risk

factors, and looks at solutions for dealing with the issue of drinking at work.

Alcohol and the working population

The heaviest drinkers, and thus those with the greatest likelihood of experiencing alcohol problems, tend to be concentrated in those of working age.

There are four ways in which alcohol consumption can negatively affect the economy [5]:

- Premature mortality due to alcohol-related accidents and illness, which reduces the size of the labour force

- Higher unemployment as heavy drinkers find it harder to find and/or stay in work

- Absenteeism: heavier drinkers tend to miss more days of work

- Presenteeism: workers’ productivity may be impaired by their drinking even if they make into work

Official statistics show that employed people are more likely to drink heavily than unemployed people [6], and that the proportion of workers drinking excessively is highest in managerial and professional occupations (where about a third of staff (36% in 2017) report heavy drinking) [7]. Further, 69.5% of this group drank any alcohol in the week before interview in 2017, compared to 51.2% of those in routine and manual occupations [8].

Market research suggests 30% of workers themselves see drinking as a way to relieve work

stress.

Among workers, official data on alcohol-related mortality by socioeconomic classification has suggested that ‘routine workers’ are at greater risk of dying from an alcohol-related disease than those in higher managerial and professional jobs.

Men whose jobs are classified as ‘routine’, such as van drivers and labourers, face 3.5 times the risk of dying from an alcohol-related disease than those in higher managerial and professional jobs. Women in ‘routine’ jobs, such as cleaners and sewing machinists, face 5.7 times the chance of dying from an alcohol-related disease than women in higher professional jobs such as doctors and lawyers [9].

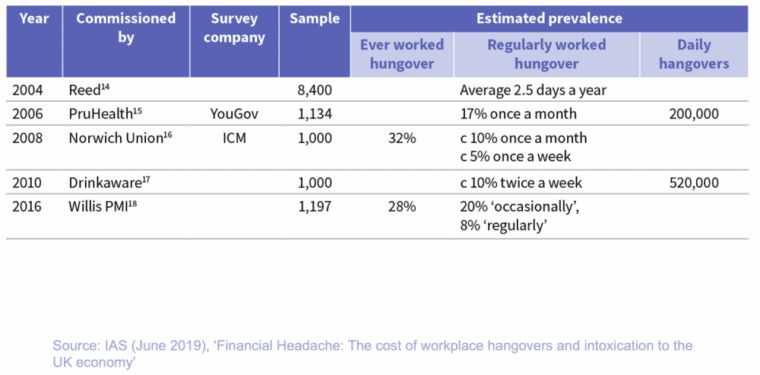

A number of studies (though not all) indicate that drinking can impair people’s performance at work – unsurprising given that alcohol has negative effect on cognitive and motor skills long after it has been consumed. Heavier drinkers tend to report lower productivity, lower quality work and are more likely to get into arguments or accidents. Previous non-academic sources have estimated prevalence of hungover working, as summarised in Figure 1 [10].

Figure 1 Previous UK surveys on working with hangovers

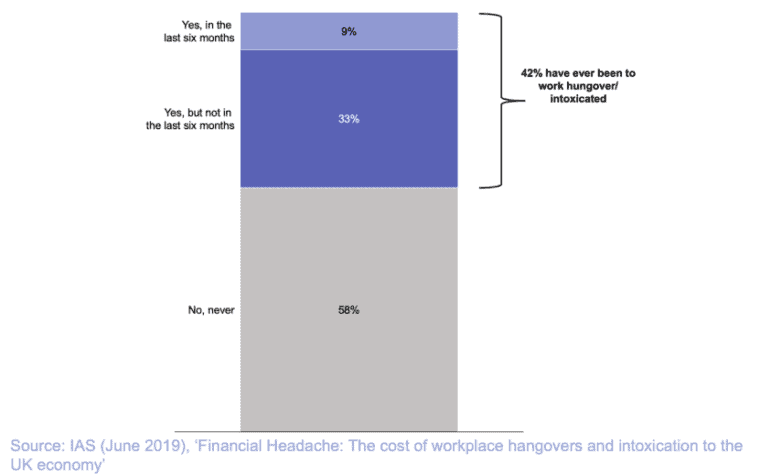

Survey research from IAS improved on these estimates. IAS has found that 42% had ever gone to work hungover or under the influence of alcohol, and 9% had done so in the last six months (see Figure 2). On average, these workers rated their performance at work to be 39% less effective than usual.

Figure 2 Have you ever been to work hungover or under the influence of alcohol?

This work suggests that people working whilst hungover or under their influence of alcohol – presenteeism – costs the UK economy between £1.2bn and £1.4bn a year (see figure 3). Further to this, an Impact Assessment paper on minimum pricing calculated lost productivity due to alcohol in the UK (including premature death of working age people, unemployment, and sickness absence) at about £7.3bn per year (at 2009–10 prices) [11].

Figure 3 Formula for calculating economic cost

The predictors and effects of workplace drinking

Key predictors

There are a number of factors relating to the workplace which influence a person’s level of alcohol consumption. For example, some studies show a correlation between working hours and amount of alcohol consumed; one involving a sample of 300,000 subjects across Europe, Australia and North America identified that those who work more than 48 hours a week are 11% more likely to drink alcohol at risk levels than those working a standard week [12].

A government-commissioned independent review into the impact on employment outcomes of drug or alcohol addiction, conducted by Dame Carol Black, was published in 2016.

Stakeholder responses to the review gave evidence of particular risk factors, among them long working hours, jobs with high physical demand and risk of injury, monotonous work, poor supervision and job insecurity [13]. These are highlighted in the summary of key predictors for problematic drinking in the workplace by successive studies over the past 20 years.

Figure 4 Indicators of problematic alcohol use in the workplace

The review also states that different professions and groups have been shown to use substances as a coping strategy [14].

An investigation by think tank DEMOS into the drinking culture among Britain’s youth suggested that graduate schemes attached to some leading professions come with ‘expectations of fairly aggressive drinking cultures’, including regular networking events involving alcohol.

The report ‘Youth drinking in transition’ indicated that ‘work-related drinking can be important at many stages of working life – from first initiation with colleagues through to appearing to help with achieving business objectives and career progression in some sectors. Some employers may even use drinking culture explicitly as a draw for job candidates in the first place’ [15].

Conversely, more than two fifths (43%) of young workers thought that not drinking alcohol was a barrier to fitting in socially at work, which is described as problematic ‘because of the risk of marginalising staff of religious and ethnic minority groups or others who do not drink’ [16].

How productivity is affected

As has already been discussed, alcohol consumption during working hours or attending work hungover can impact productivity. This happens through a variety of routes. Studies have shown that a raised blood alcohol level while at work jeopardises both efficiency and safety by increasing the likelihood of mistakes, errors of judgement, and accident proneness. There is evidence to show that impairment of skills begins with any amount of alcohol in the body [17], which can have serious consequences for workers employed in industries centred on transportation (eg pilots, drivers of public transport, ferry drivers, delivery drivers, heavy goods vehicles / freight drivers, etc), heavy machinery and construction.

There are no precise figures of the number of workplace accidents attributable to alcohol, but the International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimated that up to 40% of accidents at work involve or are related to alcohol use [18,19].

If problem drinking persists, it can lead to a range of social, psychological and medical problems for an employee, including dependence, which may be associated with drinking or being intoxicated during working hours, and presents in the continued deterioration of skills and increasing interpersonal difficulties.

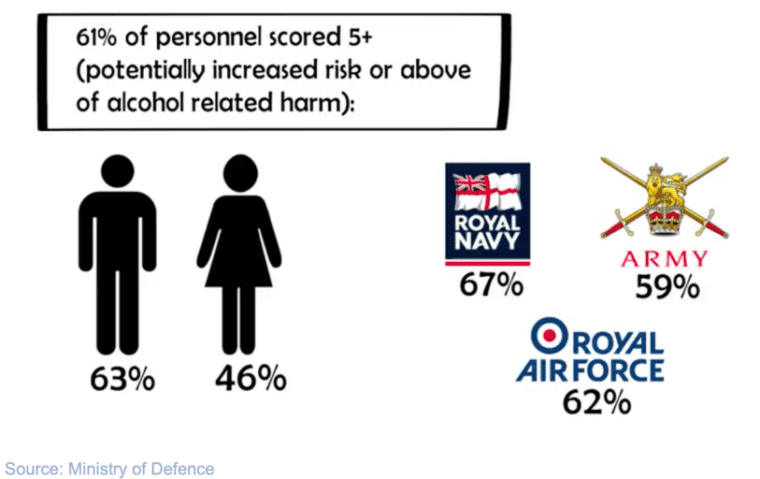

Furthermore, those who engage in such drinking behaviours in workplace environments run a higher risk of being disciplined by their employers for various kinds of misconduct. In the armed forces, for instance, alcohol is reported to be a factor in 81% of court martial cases [20], while the Ministry of Defence report Alcohol usage in the UK armed forces found that in the 12 months leading to May 2017, 61% of personnel were drinking at levels that placed them at a potentially increased risk or above of alcohol-related harm (see figure 5 for full breakdown) [21].

Figure 5 Alcohol usage in the UK armed forces: 1 June 2016 to 31 May 2017

Where there is clear evidence of alcohol affecting an employee’s behaviour or performance in the workplace (eg recklessly comes to work having been drinking), dismissal is likely and will be held to be fair at an Employment Tribunal, especially where the work in question is particularly sensitive, such as where there may be a risk to others [22].

Putting alcohol policies to work

Many organisations now operate workplace alcohol policies designed to ensure that employees are sober during working hours and to identify and help employees with that require support. They are most commonly found among large firms and those which are safety-sensitive, such as transport.

However, there are many organisations in which either the workplace drinking culture remains, or the requisite safeguards to prevent alcohol misuse and its effects are absent. Acknowledging this discrepancy, Dame Carol Black’s 2016 report recommended that preventative action to address the issue on the part of employers could ‘guard against future dependence and improve productivity and workplace culture more generally’ [23].

Unions

In recent years, several unions have urged organisations to incorporate measures addressing alcohol misuse into their workplace policies. In its submission to the National Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy (February 2003), the Trades Union Congress (TUC) called for further development of workplace alcohol policies. The report, titled Drink and work – a potent cocktail, stated that people were drinking more than ever before, but that few employers had alcohol policies in place to tackle the problems arising from problem drinking [24]. It referred to an Alcohol Concern survey which showed that three-in-five employers (60%) were experiencing problems as a result of staff drinking. Separate research from the CIPD and People Management magazine published in 2007 found that nearly one third (31%) of organisations have dismissed employees as a result of alcohol problems, that 42% did not even have alcohol or drug policies, and of the rest that did, very little was done to actively promote them [25]. Unions have also addressed the issue of drug and alcohol testing in the workplace in recent years, raising concerns about the outcomes for employees subject to this. This is exemplified by local government workers’ union Unison’s qualified support of the decision of Calderdale Council in West Yorkshire to introduce drug and alcohol testing for its employees in 2013; the union ‘asked the council to set out clearly action it will take about continued employment where council workers fail such a test’ [26].

The TUC argued that there exists a serious lack of understanding from employers on the effects of alcohol on the workplace environment, and that the government ought to fund more research into this growing problem. Its report concluded that a partnership approach between unions, employers and government would be the best way to address the issue, and suggested the following ways in which all three parties might do so [27]:

- The government should fund research looking at the extent of the misuse of alcohol by individuals at work, its effect on the workplace and its cost to the nation. The government could also offer financial incentives to those employers currently offering counselling and other types of employee assistance programmes to encourage more workers to come forward and admit their alcohol problems

- Employers who don’t have alcohol policies should draw them up in consultation with unions in the workplace. Policies should cover such topics as tackling the causes of excessive drinking, confidentiality, counselling, screening, testing and occupational health services

- Unions can play their part by training and providing information to union reps on dealing with workplace alcohol issues, and by helping those members trying to deal with their drink problems through rehabilitation schemes.

Support from employers

There has also been some concern about the provision of support for professionals who have issues with alcohol.

In 2011, a newspaper article brought to national attention the calls of healthcare experts for urgent action to tackle the ‘significant challenge’ of rising levels of alcohol problems and substance abuse among professionals including doctors, dentists and lawyers [28].

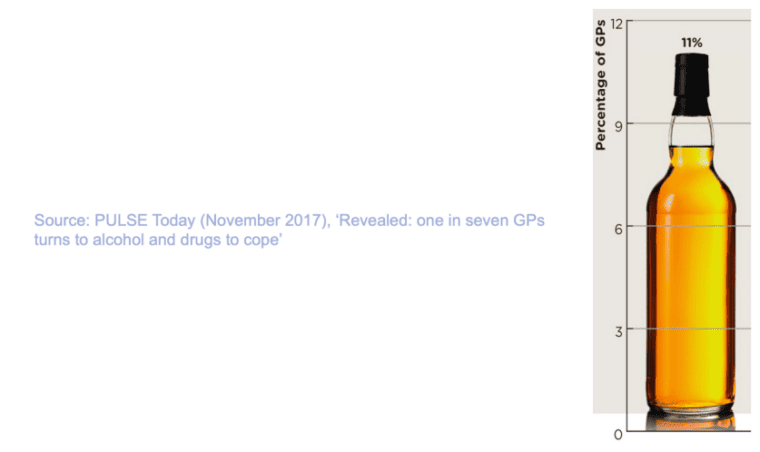

The problem persists among the medical profession – in 2017, a Pulse magazine survey found that around 11% of GPs had turned to alcohol to help them ‘deal with work pressures’ (see Figure 6) [29].

Figure 6 Percentage of GPs turning to alcohol as a result of work pressures

The BMA issued revised guidance on alcohol misuse in the workplace in early 2014, which

was updated in 2016 [30].

Some experts have also noted a rise in medical tourism, due to the work hard, play hard culture exported abroad by UK professionals who travel abroad for business. Alastair Mordey, the programme director of the Cabin, a substance abuse clinic in Chiang Mai,

Thailand, said that rehabilitation centres in the country were seeing a lot of professionals coming in, particularly from London, and that in Britain ‘there is a silent mass of professionals who are functioning… but they are in workplaces where you really wouldn’t want them to be’ [31].

A survey from the Chartered Institute of Personal Development found only 33% of employers have formally trained their managers on alcohol and drug policy and management issues, and 43% of workplaces did not have a specific alcohol policy, while just 27% had capability procedures for managing staff with alcohol problems [32]. Dame Carol Black’s review suggested that the low take-up of workplace policy solutions may be the result of how challenging employers may find it to change the workplace culture in order to help employees to manage their hidden substance misuse problems [33]. The BMA website lists organisations providing services specifically for those in the medical professions who are struggling to cope with alcohol dependence and addiction [34].

Cultural shifts

Notable employers that have taken steps to change workplace drinking culture include Lloyd’s of London, who in 2017 introduced a ban on staff drinking alcohol during working hours. This new alcohol policy was introduced to ‘bring the institution into line with others in the industry rather than being related to an increase in alcohol-related incidents’ [35].

In the legal world, the Financial Times declared that the profession is ‘in the middle of a crisis over its drinking culture’. The business newspaper observed that ‘as the #MeToo movement spreads from Hollywood to the corporate world, the role alcohol plays in alleged misconduct issues at top-tier firms has come under scrutiny’ [36].

As mentioned earlier (see figure 4), the problem of drinking culture extends to the armed forces: researchers found that alcohol misuse is more common in the armed forces than post-traumatic stress disorder [37].

Moves are being made to combat drinking culture in the armed forces. Following a high-profile sex offence court case, Judge Advocate General Jeff Blackett said:

I would like to put it on record that too many offences occur because of the abuse of alcohol, more needs to be done by the services to address this issue [38].

The Ministry of Defence Alcohol Working Group subsequently sought to review workplace policy to identify solutions to the problem of alcohol misuse in the armed forces, identifying 61% of military personnel who drink at risky or harmful levels [39].

The MoD’s report ‘Alcohol Usage in the UK Armed Forces, 1 June 2016 – 31 May 2017’ highlighted the routine dental inspections that Forces personnel undertake as an opportunity for delivering Identification and Brief Advice (IBA) to promote behaviour change amongst at-risk drinkers throughout the workforce.

The MoD also stated that the introduction of the AUDIT-C tool at scale in the UK Armed

Forces population to deliver IBA represented ‘one aspect of Defence’s broader population

approach to promoting sensible drinking in the UK Armed Forces’.

Developing a workplace alcohol policy

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) website contains a guide for employers on how to develop an alcohol strategy for the workplace. It highlights the legal obligation for employers, under The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, to ensure the health, safety and welfare of their employees:

If you knowingly allow an employee under the influence of excess alcohol to continue working and this places the employee or others at risk, you could be prosecuted. Similarly, your employees are also required to take reasonable care of themselves and others who could be affected by what they do [40].

Today, employers are also obliged to look for signs of alcohol dependent behaviour in their staff, for although an employee found drunk on duty is at risk of being dismissed for gross misconduct, employment protection law is sensitive to the underlying problems of alcohol dependence. Employers are therefore required to treat dependence as a form of sickness, thereby giving an employee the opportunity to overcome the problem.

Ultimately, an alcohol problem ought to be regarded as primarily a health issue rather than an immediate cause for discipline. This approach is supported by the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS), the ILO, and the Employment Appeals Tribunal [41].

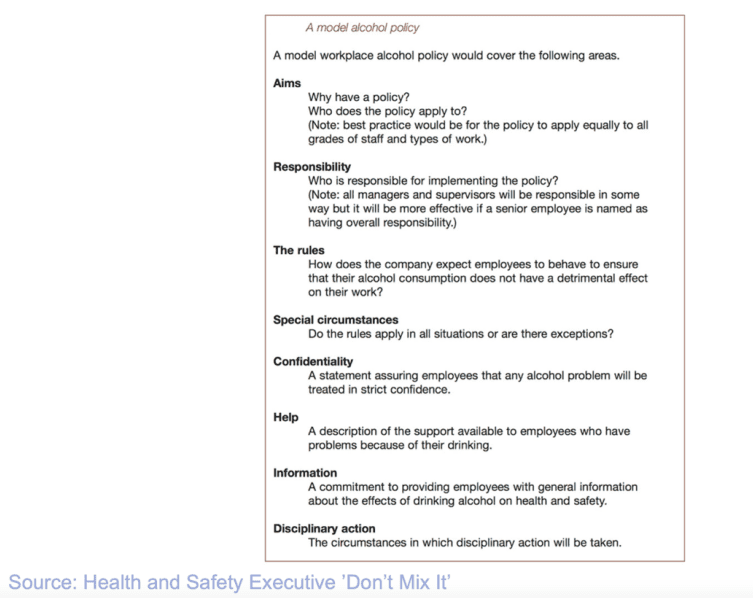

The HSE guide includes a model alcohol policy framework that employers can use as a template (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 A model workplace alcohol policy

In addition, the legislation of Human Rights Act 1998 says: ‘A drugs and alcohol policy is justified where the safety of the public is at risk’ [42].

Rules for commercial and at-work drivers

The rules for commercial at-work drivers follow national drink-driving legislation. The Transport and Works Act 1992** introduced the 80mg% legal limit for operational staff at British Rail, which has led to today’s established framework of limits and offences (under The Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003) that can be committed by people working in the field of aviation, transport and shipping [43]. Driving while under the influence – whether for work or leisure purposes – is covered by the 1988 Road Traffic Act, which stipulates a legal blood-alcohol limit of 80mg% while behind the wheel of a motorised vehicle. This follows for pilots and their cabin crew working in the aviation industry (as per Part 5 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003), while professionals of the equivalent positions in the shipping industry are subject to a prescribed blood-alcohol limit of 50mg% (as per Part 4) [44].

In some industries such as rail and maritime, alcohol testing is already mandatory and necessary as a regulatory requirement. For the majority however, there is no right to mandatory alcohol testing [45]. A BRAKE-commissioned survey found fewer than half of employers (44%) would dismiss an employee driver for driving over the legal alcohol limit. It also revealed:

- More than half never test employees for alcohol (55%) or drugs (57%)

- Six in ten (62%) take disciplinary action against employees found to have any amount of alcohol or illegal drugs in their system at work, but only three in ten (30%) would dismiss employees for this

- Fewer than half (47%) educate drivers on the risks of drug-driving, and only slightly more (50%) educate drivers on the risks of drink-driving.

The road safety charity urges companies to implement zero-tolerance policies on at-work

drink-driving [46].

** Under the Transport and Works Act 1992, certain rail, tram and other guided transport system workers must not be unfit through drink while working on the system. The operator of such a system must exercise all due diligence to avoid those workers being unfit.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2018), ‘Table 4: Drinking habits and economic activity, Great Britain, 2014 to 2017’ in ‘Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017‘

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2018), ‘Table 7: Drinking habits by socio-economic classification, Great Britain, 2014 to 2017’ in ‘Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017’

- Woodhouse, John (April 2017), ‘Alcohol: Minimum pricing’, House of Commons Library, p. 7, from Home Office (November 2012), ‘Impact Assessment on a minimum unit price for alcohol‘, p. 5

- Bhattacharya, A. (2019), ‘Financial Headache; The cost of workplace hangovers and intoxication to the UK economy’. London; IAS

- Bhattacharya, A. (2017), ‘Splitting the Bill; Alcohol’s Impact on the Economy’. London; IAS

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2018), ‘Table 4: Drinking habits and economic activity, Great Britain, 2014 to 2017’ in ‘Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017‘

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2018), ‘Table 7: Drinking habits by socio-economic classification, Great Britain, 2014 to 2017’ in ‘Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017‘

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2018), ‘Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2017‘, Statistical bulletin

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (May 2011), ‘Alcohol death rate greater for women and men in routine jobs‘, Health Statistics Quarterly 50, p. 1

- Bhattacharya, A. (2019), ‘Financial Headache; The cost of workplace hangovers and intoxication to the UK economy’. London; IAS

- Woodhouse, John (April 2017), ‘Alcohol: Minimum pricing’, House of Commons Library, p. 7, from Home Office (November 2012), ‘Impact Assessment on a minimum unit price for alcohol‘, p. 5

- British Medical Journal (January 2015), ‘Long working hours are linked to risky alcohol consumption’

- Dame Black, Carol (December 2016), ‘Drug and alcohol addiction, and obesity: effects on employment outcomes’, p. 47

- Dame Black, Carol, ‘Drug and alcohol addiction, and obesity: effects on employment outcomes’, p. 47

- DEMOS (September 2016), ‘Youth Drinking in Transition’

- DEMOS, ‘Youth Drinking in Transition’

- Institute of Alcohol Studies, ‘Health impacts factsheet’

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (1996), ‘Don’t mix it: A guide for employers on alcohol at work‘, p. 1

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) (January 1996), ‘Management of alcohol- and drug-related issues in the workplace‘, p. 17

- Matthews, Amy (July 2014), ‘Alcohol a Factor in 81% of Court Martial Cases’, Forces Network

- Ministry of Defence (July 2017), ‘Alcohol usage in the UK armed forces: 1 June 2016 to 31 May 2017’ House of Commons Hansard (February 2017), ‘Armed Forces Covenant’, volume 620

- Your Rights, ‘Drug Taking and Drinking’, Liberty

- Dame Black, Carol (December 2016), ‘Drug and alcohol addiction, and obesity: effects on employment outcomes’, p.47

- MEPMIS (January 2003), ‘Trades Union Congress (TUC): Drink and work – a potent cocktail‘

- HRM Guide (September 2007), ‘GGG CIPD Survey Highlights Drug And Alcohol Misuse’

- Douglas, Joanne (August 2013), ‘Calderdale becomes first Yorkshire council to drug and alcohol-test employees’ The Huddersfield Daily Examiner

- MEPMIS (January 2003), ‘Trades Union Congress (TUC): Drink and work – a potent cocktail‘

- McVeigh, Tracy (November 2011), ‘Alarm at growing addiction problems among professionals‘, The Observer

- PULSE (November 2017) ‘Revealed: one in seven GPs turns to alcohol and drugs to cope’

- British Medical Association (BMA) (July 2016), ‘Alcohol, drugs and the workplace – the role of medical professionals’

- McVeigh, Tracy, ‘Alarm at growing addiction problems among professionals‘, The Observer

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2007), ‘Managing drug and alcohol misuse at work’, London, CIPD

- Dame Black, Carol, ‘Drug and alcohol addiction, and obesity: effects on employment outcomes’, p. 47

- British Medical Association (BMA), ‘Sources of support‘

- The Financial Times (February 2017), ‘Lloyd’s of London ban alcohol during working hours’

- Financial Times (January 2020), ‘Drinking culture in legal world under scrutiny following scandals’

- The Conversation (April 2019), ‘Alcohol misuse is more common in the armed forces than post-traumatic stress disorder’

- Armed Forces Network (June 2017), ‘Rape Case Judge: Forces Need To Tackle Drinking Problem’

- Alcohol Policy UK (August 2017) ‘Armed forces deploy brief interventions: will it work?’

- Health and Safety Executive (1996), ‘Don’t mix it: A guide for employers on alcohol at work’, p. 4

- Stone, I (2005)., Employers liability and responsibility, in Ghodse, H (ed)., ‘Addiction at work: tackling drug use and misuse in the workplace‘, London: Gower

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Legislation.gov.uk, ‘Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003‘

- Part 5: Aviation – alcohol and drugs ; Part 4: Shipping – alcohol and drugs

- Landau, Philip (April 2013), ‘Spectre of workplace alcohol tests hang over employees’, The Guardian

- BRAKE (May 2014) ‘Brake calls for zero-tolerance on at-work drink- and drug-drivers’

View this report