A time for change

The second half of 2022 has seen the World Health Organization (WHO) publish the Global Alcohol Action Plan and the European Alcohol Framework. A group of leading alcohol researchers has updated Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity (ANOC), the latest in a series of evidence reviews dating back to the mid 1970s, and in the last month there has been a flurry of data from across the UK on alcohol consumption and harm.

So there has been guidance from the WHO and ANOC, there has been different approaches to the adoption of that guidance within the UK and there is some data on outcomes. In this blog I’ll look at what this tells us about the Golden Thread of research, policy and outcomes.

What has the WHO and ANOC said?

The core message from the WHO reinforced the importance of effective tax and pricing policies on the affordability of alcohol, controls on access through numbers of outlets, and age controls and restrictions on marketing. While the upstream prevention measures have the highest impact in reducing harm, treatment and support measures are also recognised by the WHO and the ANOC authors as important, as is accurate consumer information on products.

So while ANOC highlights new research that advance our understanding, the message on effective prevention has not changed.

The challenge remains one of implementation, and the countries of the UK have a variable and inconsistent record on effective, comprehensive and sustained action.

UK deaths from alcohol rise again

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published their annual report on UK alcohol-specific mortality for 2021 in early December 2022. This showed alcohol-specific deaths at an all time high in the UK, with an increase of more than 25% in the past two years.

It is now well established that one impact of lockdown was to further increase the consumption of those who were already at the greatest risk from their high levels of consumption and sadly many have died a premature and avoidable death. So while overall consumption has remained relatively stable since 2019, alcohol-specific mortality has increased considerably, and if these trends continue, the impact on public health will be significant.

How alcohol-specific deaths are defined is an important part of the picture. This was reviewed in detail by the ONS in 2017. This review narrowed the definition of an alcohol death to where the recorded cause of death was very likely to be fully due to alcohol. In practice this means 78% of these deaths are from alcohol-related liver disease, with the rest due to alcohol dependence and alcohol poisoning.

So deaths from alcohol-related cancers, accidents, suicide and heart disease are not included in the published numbers. Estimates are that the total burden of alcohol deaths is 3-4 times the number published annually by the ONS. Drug deaths and alcohol deaths are identified, investigated and recorded very differently and the published numbers of deaths for alcohol and other drugs cannot be compared without complex further analysis.

While the ONS data is not an indicator of the true burden of mortality from alcohol, a clear and unambiguous definition enables us to track trends across time and place. That means we can be confident that the overall increase in the past 2 years and the indicators of regional trends in different parts of the UK reflect the real changing impact on individuals and families.

The MUP effect

Alcohol policy is complex and involves many layers of government including international agreements. Within the UK, the Scottish Government has been the most active in using its powers to reduce harm. Wales has been active notably with the introduction of Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) in March 2020.

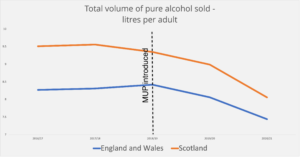

Have the Scottish measures made a difference to consumption? The estimation of alcohol consumption from available data is not a simple task and Public Health Scotland has worked hard to establish and refine estimations. This analysis showed that in comparison to England, alcohol consumption fell in Scotland by 3% overall and 3.6% in off sales. In the UK “off sales” means stores selling alcohol for home drinking, and this sector is now dominated by the big supermarket chains, whose buying power allowed them to sell some alcohol at very low cost before MUP was introduced.

After MUP was introduced, supermarket sales fell more than sales in independent stores who have generally welcomed the ‘levelling of the playing field’. Pubs and restaurants were closed or limited in trading for much of 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic, and there was very limited and often no restriction on off sales. As Scotland and England had very similar lockdown approaches during the pandemic, the comparison of the countries remained valid.

Which categories of alcohol have been most affected in Scotland with the introduction of MUP? There were no surprises, with the lowest cost apple and pear ciders (who take advantage of their very favourable tax rates) and own brand vodka and gin (which is cheap to produce) having the lowest pre-MUP prices. These products had the greatest increase in prices after MUP introduction and the greatest fall in sales.

These products, the strong cheap ciders and spirits, were the drinks that clinicians like myself were hearing about from patients from the mid-1990s when we saw alcohol-specific deaths increase three fold in Scotland. As the price gap between pub and home drinking increased, the heaviest drinkers rarely drank in pubs, becoming more isolated and more ill by the time they came for help. The patients didn’t want the situation they had ended up in, they wanted change, and tackling tempting low cost alcohol seemed to be an essential part of helping them and generations to come. Sophisticated modelling and analysis subsequently supported that judgement and it is welcome to see these products decline in sales and in some cases disappear altogether.

Alcohol consumption per head in Scotland is now at its lowest level for 25 years and while alcohol mortality in Scotland has risen since 2020, the increase has been less than the rest of the UK. Consumption and harm levels – which for decades had been substantially higher than the rest of the UK – are now similar to the North of England and Northern Ireland.

So the UK experience supports the WHO and academic analysis. Action on price reduces consumption among at risk drinkers, MUP has predictable effects on the products aimed at the heaviest drinkers and there are measureable population health benefits from this.

Alcohol policy is a contested space, with economic operators aggressively defending their interests. However the evidence of what works continues to accumulate and will keep knocking at the door of governments.

Written by Dr Peter Rice, addiction psychiatrist, chair of the Institute of Alcohol Studies and SHAAP steering group member.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.