I am a doctor – a psychiatrist for nearly 40 years – and as is the case for most health care professionals, I have come across patients who have been harmed by alcohol on an almost daily basis.

Yet I enjoy a drink and a few years ago helped my daughter open a wine bar in Ealing. This seemingly paradoxical love-hate relationship with alcohol is very common and reflects a number of factors, not least of which is that alcohol has been intimately involved in most aspects of western life for millennia. However in the past few decades we have gained a much clearer view of how it works to deliver its benefits and harms. It is this knowledge that allows us to optimise the path between these two effects of alcohol.

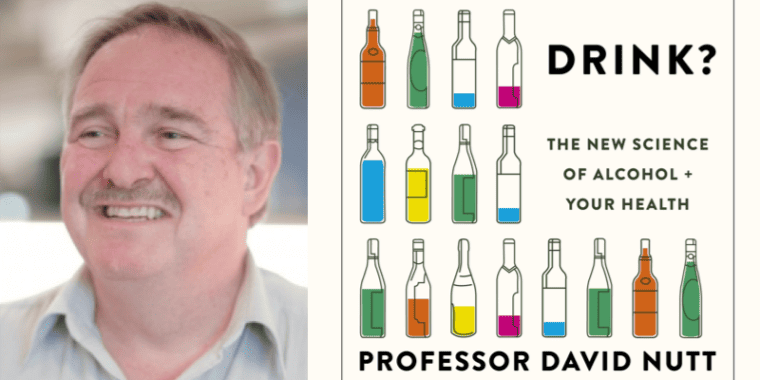

My recent book Drink? was written to help both health care professionals and drinkers make sense of the complex history, pharmacology, benefits and harms of alcohol.

We now have a good understanding of the pharmacology of alcohol and this reveals ethanol to interact with a wide range of different neurotransmitters in the brain. For most people drinking alcohol is part of social events; in Western society alcohol is part of most human celebrations and commiserations. This reflects the anxiety reducing effects of alcohol which occur with the first drink or two (one to two units) and are mediated via an enhancement of GABA function (the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter for the central nervous system).

But a significant proportion of drinkers consume more than a couple of drinks, and some lose control quite quickly, resulting in a binge. This loss of control induced by higher concentrations of alcohol probably reflects interactions with a series of other neurotransmitters. Alcohol enhances the release of dopamine and endorphin, each of which can drive ingestive behaviours. It also blocks glutamate receptors, and these are the primary excitatory system in the brain – responsible for maintaining wakefulness and memory encoding. Blocking glutamate function leads to altered judgments, confusional aggression and blackouts. Also, the brain adapts to glutamate receptor blockade by up-regulating these receptors so when alcohol levels fall there is excessive glutamate activity. This explains the sleeplessness and jitteriness of withdrawal and likely contributes to brain damage that is so common in chronic heavy drinkers.

These pharmacological insights are leading to new treatment approaches such as nalmefene (to block endorphin effects). They also underpin the move to develop GABA-targeted alternative drinks that can deliver sociability without the negative effects of alcohol.

What are the implications for people who still want to use alcohol for its good effects but avoid the harms?

Keeping close to the current UK government guidelines of no more than 14 units a week will virtually eliminate serious harms (unless you take them in a binge). I think the key is mindful drinking, only taking drinks that give you the pleasures you seek and avoiding those that are just routine or habitual.

Because if the prime benefit of alcohol is social engagement, which in itself magnifies the positive impact of alcohol, then good advice is to avoid drinking alone. Another good tip is when drinking with a partner of an evening NEVER open a second bottle, thus avoiding the risk of disinhibition leading to the temptation to finish that bottle too!

Drink? contains a number of other ideas that people can use to regulate their intake, especially avoiding drinking to self-medicate for chronic stress or mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. I think everyone who drinks should be aware of exactly how much they drink per week, in the same way they would know their weight, waist size, blood pressure and cholesterol, and they should always be trying to reduce each.

Written by David Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and CRO of GABA Labs, a company he set up to develop functional alternatives to alcohol based on selective targeting of certain GABA receptor subtypes.

His book Drink? is published by Yellow Kite books here. A version with US data, regulations and recommendations is also available here.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.