Exceptional work is being done throughout the world to mitigate the ever-escalating crisis of harms caused by the criminalisation of drugs. Along with directly operating harm reduction responses like safe consumption sites, drug testing, Naloxone trainings, and distribution of safe supplies, drug user organisations are making clear and evidence-based demands for large-scale provision of a legal, regulated, and safe supply of drugs to stem the tide of toxic and fatal poisonings (which reached almost 1,300 deaths in the first seven months of 2022 in the Canadian province of British Columbia).

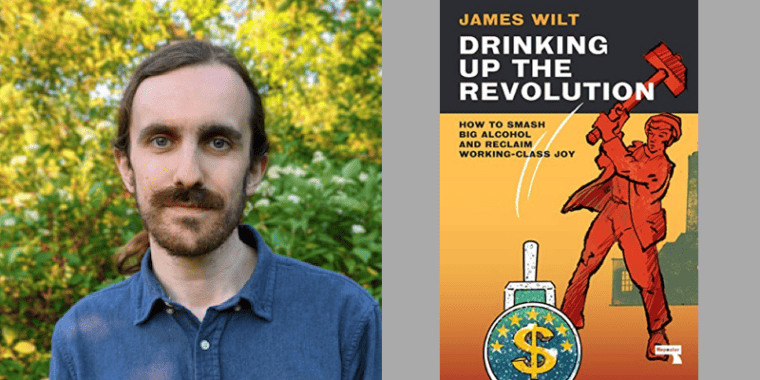

As I argue in my new book, Drinking Up the Revolution, this essential transformation towards compassionate drug policy must be done in a way that learns from the ongoing catastrophe of alcohol’s production, distribution, and retailing for private profits. Alcohol is “no ordinary commodity,” contributing to at least three million global deaths via acute harms, chronic diseases (including cancers), and alcohol use disorders, along with countless other social issues. These harms are overwhelmingly caused by the substance of alcohol itself, not a toxic or contaminated variation of it.

Yet alcohol continues to be sold in a highly reckless way that constantly increases its ubiquity — and most importantly, its profitability — to benefit enormous oligopolistic multinationals like AB InBev, Heineken, and Diageo (which I term “Big Alcohol” in the book). This domination of alcohol supply by commercial interests is a major public health crisis.

Profit-seeking as a public health crisis

This ubiquity and profitability isn’t a “natural” or inevitable outcome of humanity’s ancient interest in alcohol use. While the substance has been used extensively throughout time — often in very high-risk ways — the contemporary global availability of commercial supply in supermarkets, liquor stores, and most recently online delivery far exceeds anything in the past.

Between 1990 and 2017, total global alcohol consumption increased by 70 percent, from 21 billion litres to almost 36 billion litres, and is expected to increase by almost 20 percent more by 2030. Such conditions are the result of decades of political struggle by the extremely concentrated and powerful industry of Big Alcohol and its army of lobby groups and social aspects/public relations organisations (SAPROs) to constantly expand consumption through a wide variety of means, including deregulating sale restrictions, entrenching voluntary “self-regulation” of marketing and labelling, rebuffing price increases, undermining the growing scientific consensus on alcohol’s impacts, and much more.

These efforts have largely succeeded in further normalising alcohol use, particularly in contrast to global restrictions on tobacco, ensuring that consumption continues to grow for decades to come. This growth has been fabulously lucrative as well, with David Jernigan and Craig S. Ross describing alcohol producers as “among the world’s more profitable large companies per dollar invested.” Much of this consumption is well above evidence-based low-risk drinking guidelines, with a 2018 study finding that almost two-thirds of industry revenue in England comes from risky drinking. Higher industry necessitates higher-risk drinking and the countless resulting harms.

As part of the next phase of competition-driven accumulation, Big Alcohol is rapidly turning its attention to industrialising countries in the Global South with large populations and increasing consumer spending capacity, including China, India, Vietnam, and Nigeria. For instance, Diageo excitedly reports that “600 million new legal purchase age consumers are expected to enter the market globally by 2032,” while Pernod Ricard proclaims that because it has half its operations in “emerging markets” it is “a perfect position to be in, especially when two-thirds of global industrial growth will be driven by China and India alone.”

Many countries in the South have very weak alcohol industry regulations — in some cases seeing Big Alcohol directly draft regulations for countries — and underdeveloped infrastructures; the crisis of alcohol-related infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, accounts for a significant portion of deaths in such regions due to overcrowded housing and lack of high-quality healthcare infrastructure.

Alcohol-related deaths are already extremely high in such countries and increased ubiquity of alcohol will only make it far worse.

Restricting supply and imagining public alternatives

While alcohol is used for many interrelated subjective reasons that can be shaped and negotiated by individual drinkers and cultures — relaxation; sociability; self-medication for pain, trauma, and alienation; and much more — this is fundamentally a political and structural crisis.

Alcohol is only consumable at current volumes because of commercial production. The World Health Organization and many public health organisations have long worked to advance a series of evidence-based “best buys” including higher pricing and restrictions on advertising and availability of alcohol. These restrictive supply-side measures are crucial to reducing alcohol-related harms, and should be augmented by plain packaging regulations, mandatory health warnings and nutritional labelling, and development of a global binding treaty to coordinate policies. Gradual privatisation of remaining state-owned retailers should be halted and public ownership of industry prioritised to mitigate the profit motive.

But the public health response needs to go beyond merely restricting supply. It also needs to provide viable alternatives and measures to help people experience pleasure and joy in ways that don’t create death, serious injury, impairment, and major social issues; failing to take this seriously will likely result in contempt for aforementioned policies, particularly during the ongoing cost-of-living crisis. For starters, this means massively scaling up a wide range of alcohol-specific healthcare accessible through public and primary healthcare including managed alcohol programs, medication-assisted treatment, therapy and psychiatric care, and peer support groups that don’t mandate abstinence as a condition of participation.

Via public ownership and funding, there should also be the creation of many more things for people to do with their time: beautiful public spaces and amenities, exciting late-night venues where alcohol use isn’t the exclusive or primary focus, proliferation of cheap and high-quality non-alcoholic beverages, development of potentially safer intoxicants like “synthetic alcohol,” and legalisation and regulation of other psychoactive substances that could serve as viable substitutes for alcohol.

Like with fossil fuel companies and climate change, the alcohol industry cannot be regarded as a neutral or good-faith participant in negotiations for this kind of lower-risk and more pleasurable future. Massive profits are on the line for Big Alcohol. In order to advance genuine harm reduction by reducing consumption to lower-risk levels, the industry must be understood as the dominant obstacle to progress and marginalised from participation or influence as much as possible. Likewise, in the ongoing push for legalisation and regulation of other drugs, private ownership (especially by large multinationals) must be prevented, with all aspects of the trade strictly limited to public ownership and control.

Written by James Wilt, PhD candidate at the University of Manitoba and author of the recently published book, “Drinking Up the Revolution: How to Smash Big Alcohol and Reclaim Working-Class Joy” (Repeater Books).

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.