A key finding – a quarter of industry sales are made |

If all drinkers followed the recommended drinking guidelines, the alcohol industry would lose almost 40% of its revenue, an estimated £13 billion. This is one of the main findings of a new paper published in the journal Addiction.

The analysis, carried out by researchers at the Institute of Alcohol Studies and the University of Sheffield’s Alcohol Research Group, also shows that:

- Drinkers consuming more than the government’s low-risk guideline of 14 units (around one and a half bottles of wine or six pints of beer) per week make up 25% of the population, but provide 68% of industry revenue

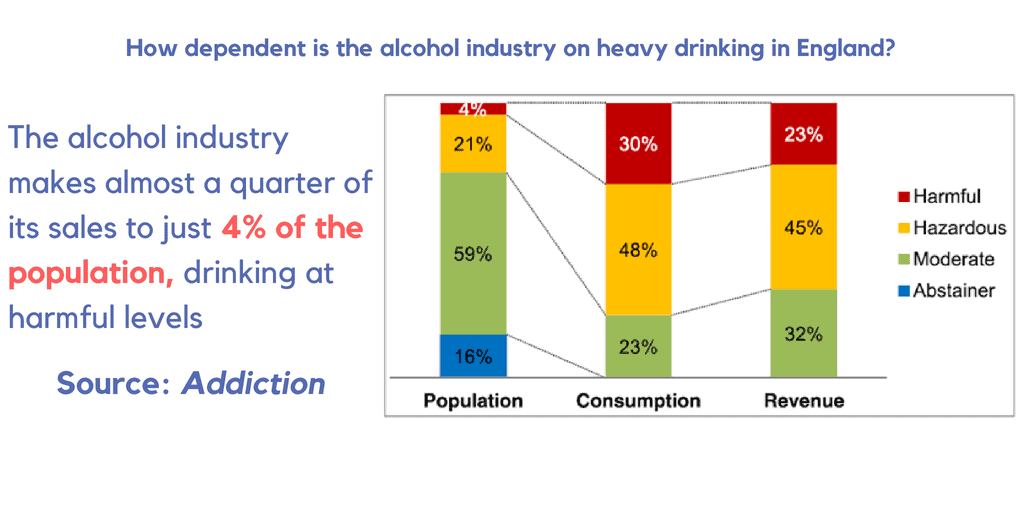

- The 4% of the population drinking at levels identified as ‘harmful’ (over 35 units a week for women, over 50 units a week for men) account for almost a quarter (23%) of alcohol sales revenue (illustrated)

The results of the study appear to contradict industry rhetoric that moderate drinking is not a threat to their business model because they can encourage drinkers to ‘drink less, but drink better’, and trade up to more expensive beverages.

Instead, many producers and retailers may in fact have a strong financial incentive to ensure heavy drinking continues in order to stay profitable – not only do a higher proportion of sales in supermarkets and off-licences (81%) than pubs, bars, clubs and restaurants (60%) come from those drinking above guideline levels, but heavy drinkers also generate a greater share of revenue for producers of beer (77%), cider (70%) and wine (66%) than spirits (50%).

The research team estimates that the average price of a pint of beer in the pub would have to rise by £2.64, and the average price of a bottle of spirits in supermarkets by £12.25, to maintain current levels of revenue if everybody were to drink within the guideline levels.

The report’s findings raise questions about the appropriateness of the industry’s continued influence on government alcohol policy.

Aveek Bhattacharya, policy analyst at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, and the lead author of the paper, said:

‘Alcohol causes 24,000 deaths and over 1.1 million hospital admissions each year in England, at a cost of £3.5 billion to the NHS. Yet policies to address this harm, like minimum unit pricing and raising alcohol duty, have been resisted at every turn by the alcohol industry. Our analysis suggests this may be because many drinks companies realise that a significant reduction in harmful drinking would be financially ruinous.

‘The government should recognise just how much the industry has to lose from effective alcohol policies, and be more wary of its attempts to derail meaningful action through lobbying and offers of voluntary partnership. Protecting alcohol industry profits should not be the objective of public policy – previous research has shown that reducing alcohol consumption would not only save lives and benefit the exchequer, but could also boost the economy and create jobs.’

Colin Angus, research fellow in the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group at the University of Sheffield, and a co-author on the paper said:

‘These figures highlight an important conflict of interest in the UK Government’s approach to reducing alcohol problems. Its decision to work in partnership with the alcohol industry is unlikely to lead to effective policies when heavy drinkers provide a large share of the industry’s revenue.

‘The scale of price rises required to maintain current levels of revenue cast serious doubt on the alcohol industry’s claims that it supports moderate drinking.’