In this month’s alert

Editorial – May 2016

Welcome to the May 2016 edition of Alcohol Alert, the Institute of Alcohol Studies newsletter, covering the latest updates on UK alcohol policy matters.

In this month’s issue, annual alcohol consumption falls worldwide for the first time this century, but the United States keeps on drinking, as do the Scots according to the latest MESAS report on sales data. Other articles include: Cheap alcohol a cause of steep rise in UK teen poisonings, Gateshead Council oversees the country’s first-ever prosecution of a below cost vendor, boss of major UK drinks seller calls for minimum unit pricing, and Ireland’s Public Health (Alcohol) Bill comes under scrutiny from EU member states.

Please click on the article titles to read them. We hope you enjoy this edition.

Global drinking levels dip for first time this century

Small declines worldwide offset by rise in US consumption

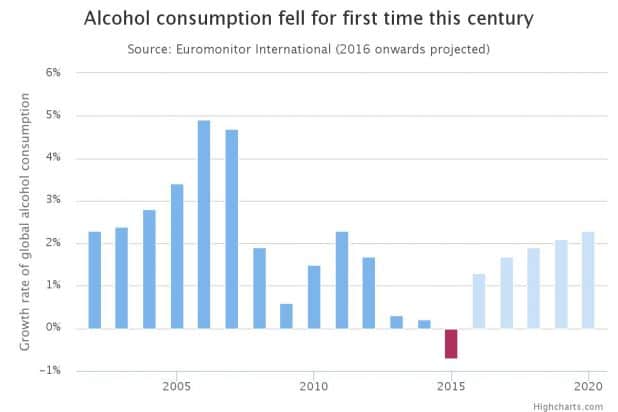

Data from market research firm Euromonitor International indicates that the world’s total alcohol consumption levels fell last year, the first time this century.

The volume of alcoholic beverages consumed in 2015 fell by 0.7% to 248bn litres, around 1.7bn less than the previous year (illustrated). The reason for the decline in volume of alcohol drunk globally has been attributed to Brazilians (-2.5%), eastern Europeans (-4.9%) and Chinese people (-3.5%) drinking less, most likely because of those region’s struggling economic fortunes. China’s economic difficulties in particular have largely contributed to the decline. The world’s biggest alcohol market (accounting for a quarter of global consumption) recorded a 3.5% drop amid relatively poor economic growth and a clampdown in extravagant lifestyles.

Meanwhile, tensions, economic sanctions and tumbling oil prices were said to take their toll on the Russian and Ukranian markets, where consumption fell by 8% and 17% respectively. Vodka, which generates around a third of global sales in that region, has been hit hardest by the decrease in consumption, according to Euromonitor.

Growth throughout Western Europe remained flat, as was also the case in Australasia. However, in North America, consumption rose by 2.3% on the previous year, resulting in the United States maintaining its position as the second highest consumer of alcohol in the world. In 2015, North Americans bought 33.8 billion liters of alcohol, an increase from 33.1 billion liters in 2014. The continent has had a stronger economy, plus the popularity of microbreweries and the craft beer movement has given alcohol sales a boost, said Euromonitor International’s senior alcoholic drinks analyst Spiros Malandrakis.

Craft beers were among the biggest beneficiaries of this growth, as well as cider, which experienced a consumption increase of 4.5%, as young consumers turned to “aspirational” and “exotic” brand alternatives. Sales of tequila and mezcal — a Mexican liquor — grew to about 275 million litres in 2015 from about 263 million litres in 2014, and sales of bourbon and other U.S. whiskey grew to 335 million litres from 322 million litres. Sales of cognac grew to almost 104 million litres from about 99 million litres. Global sales of wine grew to 27.9 billion litres from about 27.4 billion litres. Conversely, sales of vodka fell to about 3.2 billion litres in 2015 from about 3.3 billion litres, and sales of rum fell to 1.36 billion from about 1.38 billion litres over the same period.

Malandrakis said: “The trajectories of sophistication, moderation, perceived exotic credentials, accessibility and aspirational attributes remain the key driving forces fuelling pockets of buoyancy.

“It is no coincidence that [Premium English gin, Irish and Japanese whiskey and dark beer] are the flag bearers of growth [and] also happen to be the segments gaining further momentum with the ever-important millennial demographic in mature western markets,” he added.

Despite continued global economic uncertainty, Euromonitor expects alcohol consumption to recover this year, rising by 1.3% to 251.3 litres.

Blog: The paradox of waning alcohol consumption? It’s the culture, stupid!

Levels of global alcohol consumption have flatlined. Cultural changes may be one major reason why, says Dr Joan Costa-i-Font

Levels of global alcohol consumption have flatlined. Cultural changes may be one major reason why, says Dr Joan Costa-i-Font

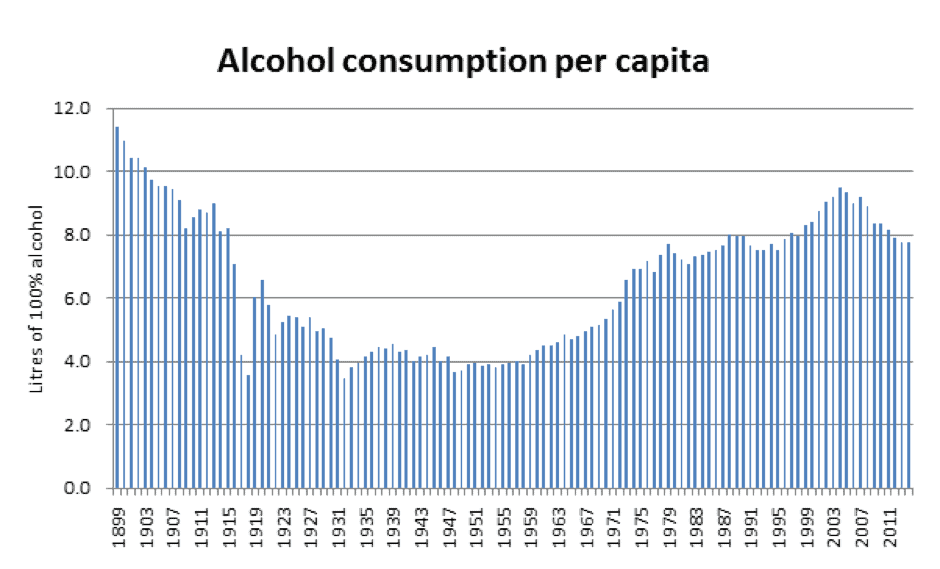

The recent release of data by Euromonitor suggest that alcohol consumption globally might have flattened. Specifically, consumption has declined worldwide to the point of a negative growth for the first time this century. This evidence is consistent with survey data for Britain suggesting that the proportion of people aged 16 to 24 who say they did not drink alcohol at all has increased by 40% since the last survey of this kind was conducted in 2005. These facts help to explain the below figure which reveals clear evidence of a declining trend in alcohol consumption per capita, peaking in 2004 (illustrated). The evidence is consistent with Danish data suggesting a reduction of yearly per capita alcohol consumption of as much as 25 litres from 1997 to 2011.

Similarly, some other evidence suggests younger generations have substituted alcohol for other (possibly healthier?) alternatives. Millennials are less seduced by a large intake of alcohol, and more generally, data from the United States indicates that 2014 saw the lowest ever levels of alcohol consumption among teenagers since records began.

Yet, what are the underlying drivers of such a trend? One could examine both the short or long-term factors on existing consumers, as well as the effects on old and new consumers separately. However, it is possible to summarise those factors in three broad groups:

- The effect of economic barriers such as higher prices (e.g. minimum prices) and low income and household budget cuts (e.g. recessions);

- Both intended and unintended consequences of policy interventions (e.g. alcohol taxation and regulation); and finally,

- The effect of wider shifts in preferences and beliefs about the roles and the acceptability of alcohol, especially among certain cohorts.

I argue that the latter effect – which economists call cultural change – seems to be behind the continuing reduction in alcohol consumption, even though other effects such as policy and economic barriers to access also play a very important reinforcing role.

Nationwide evidence seems to indicate a generational change towards more moderate consumption and, in some cases, even abstention. For instance, one could cite the effect of health information campaigns on alcohol (e.g. the effects of alcohol during pregnancy), and more generally, policies that have acted as tipping points. I shall briefly address each one of these effects.

Economic barriers still matter, if they change habits

A well-established fact is that alcohol consumption is a ‘normal good’, hence it tends to increase with income, and lower income individuals are more likely to be abstainers. Hence, changes in the socio-economic composition of a population might discourage alcohol initiation, and more specifically, recessions are said to explain falls in consumption (e.g. the recent recession in China).

That said, it is unlikely that economic conditions explain alcohol consumption patterns alone. One reason is that they might instead lower the quality of alcoholic beverages. But more importantly, the drop in alcohol consumption observed in the data seems to have taken place prior to the recession (2004 in the UK). This is not to say that economic barriers do not matter. Taxes and price interventions can make a huge difference in moderating consumption, and more generally, in modifying long term consumption habits.

Policy interventions play a role in reinforcing social norms

A second type of factor refers to the intended effects of policy interventions. This includes a number of policies, such as regulations clamping down on drink-driving, clinical guidelines discouraging women to drink during pregnancy, bans on drinking in public transport and on the availability of alcohol in some public places, to name a few. In addition, it is possible to cite unintended effects of other policies such as smoking bans in public places, which might have exerted knock-on effects on the socialising roles of drinking. The above policies in turn impact on the ‘social acceptability of an unhealthy drink culture’.

Too much alcohol is not cool anymore

This leads is to to the final explanation, namely the effect of culture; the reduced social acceptability or decline in the ‘coolness of alcohol consumption’. Culture explains, for instance, that Germany or Russia yearly consume 100 litres of alcohol per capita compared with only 3 in Morocco. In some western countries, alcoholic beverages are usually companions to foods, but can also serve to enhance people’s sociability, or can, for some – especially men – be used as a narcotic substance to cope with personal hardship. From an historical standpoint, alcohol consumption is intertwined with culture and tradition (e.g. champagne in every celebration). However, even within western societies, some groups have long taken pride of ‘being sober’ or ‘abstaining altogether’. Although it’s difficult to imagine the UK without its pubs, evidence suggests that there are 13% fewer pubs in the UK today than there were in 2002. Some of the traditional roles played by alcohol have been replaced by sport, therapy, etc. Finally, health campaigns, as much as other cited policy interventions, influence deeper attitudes and preferences towards viewing alcohol as a risky product.

We rely less on alcohol for socialising purposes than in the past. This is especially true among younger individuals, whose socialising habits are very different from that of their parents. The health-related consequences of alcohol overconsumption are more difficult to mask today than a few decades ago. Given that we expect to live longer, and prevention is the less costly route to being in good health, the value of health has increased with respect to other pleasures, and for some, excessive alcohol intake is not worth it. This does not mean alcohol will disappear from our lives, just that it might play a different role – a less relevant one perhaps – to the one it played in the past.

Originally written for IAS Blogs.

Scottish alcohol sales on the increase again

Data shows three-quarters of alcohol consumed off-trade, of which majority is sold below proposed minimum unit price level

The downward trend in the amount of alcohol sold per adult in Scotland has reversed, according to figures released by NHS Health Scotland. The trend is mainly due to more alcohol being sold through supermarkets and off-licences compared with recent years, particularly beer and wine.

The downward trend in the amount of alcohol sold per adult in Scotland has reversed, according to figures released by NHS Health Scotland. The trend is mainly due to more alcohol being sold through supermarkets and off-licences compared with recent years, particularly beer and wine.

Analysis of the most recent consumption data suggests that 10.8L of pure alcohol was sold per adult in Scotland in 2015, equivalent to 41 bottles of vodka, 116 bottles of wine or 477 pints of beer for every adult in Scotland. Almost three quarters of alcohol – 74% – was sold through off-sales (illustrated, right), which is the highest market share since recording began in 1994.

The analysis also highlights that alcohol sales in Scotland were 20% higher than in England and Wales in 2015. This was mainly due to higher sales of lower priced alcohol through supermarkets and off-licences, particularly spirits. More than twice as much vodka was sold off-sales per adult in Scotland than in England and Wales.

As well as alcohol sales, the researchers examined alcohol prices. In 2015, it was found that the average price of a unit of alcohol sold through off-sales was 52 pence (compared with £1.74 sold through on-sales, illustrated, left), which has not changed in the past two years. A large amount of alcohol continues to be sold cheaply relative to its strength. More than half of off-sales alcohol was sold at below 50 pence per unit, the initial level proposed for minimum unit pricing. The amount of beer sold below this price has increased by 11% in the past two years, equivalent to over 30 million bottles.

As well as alcohol sales, the researchers examined alcohol prices. In 2015, it was found that the average price of a unit of alcohol sold through off-sales was 52 pence (compared with £1.74 sold through on-sales, illustrated, left), which has not changed in the past two years. A large amount of alcohol continues to be sold cheaply relative to its strength. More than half of off-sales alcohol was sold at below 50 pence per unit, the initial level proposed for minimum unit pricing. The amount of beer sold below this price has increased by 11% in the past two years, equivalent to over 30 million bottles.

Dr Mark Robinson, Senior Public Health Information Manager at NHS Health Scotland, said:

“It is concerning that the recent falls in population alcohol consumption have reversed and that off-trade alcohol sales have reached their highest level. Trends in the price of alcohol sold by supermarkets and off-licences correspond with trends in the volume of alcohol sold by these retailers. Between 2009 and 2013, the average price of alcohol increased and consumption decreased. Since 2013, average price has flattened and consumption has increased. Higher levels of alcohol consumption result in higher levels of alcohol-related harm and these present a substantial public health and economic cost to Scotland. Policies that reduce the availability of low priced, high-strength alcohol are the most effective for reducing alcohol-related harms and narrowing health inequalities.”

The figures also give fresh justification to public health campaigners’ calls for introducing minimum unit pricing, a measure lawfully passed by the Scottish Government four years ago, but yet to be implemented because of a court challenge over its legality, led by the Scotch Whisky Association.

Responding to the MESAS data, Alison Douglas, Chief Executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland, said:

“Scotland is now a nation of home drinkers, with more alcohol sold through supermarkets and off-licences than ever before. This has been driven by really low prices and constant promotions encouraging us to consume more.

“More than half of alcohol in supermarkets and off-licences is sold at less than 50p per unit, while a fifth costs less than 40p per unit. The very cheapest products under 30p per unit are mainly vodkas and strong ciders which are favoured by young, vulnerable and harmful drinkers.

“The more affordable alcohol is, the more we drink, and this means more alcohol-related hospital admissions, crime and deaths. Politicians across the Scottish Parliament understood this evidence when they passed minimum unit pricing legislation four years ago. It is really disappointing that this life-saving measure has been delayed by the Scotch Whisky Association’s legal challenge. Their defence of cheap vodka and cider is somewhat at odds with the ‘iconic’ image of Scotch. Like the tobacco industry, the alcohol industry is placing profits before people’s health.

“With 22 Scots dying because of alcohol every single week and sales increasing, minimum pricing is desperately needed.”

Adapted from NHS Health Scotland press release / Alcohol Focus Scotland response. Infographics that summarise the findings and supporting datasets are available on the NHS Health Scotland website.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions in 2015 – is the tide turning?

From Alcohol Policy UK

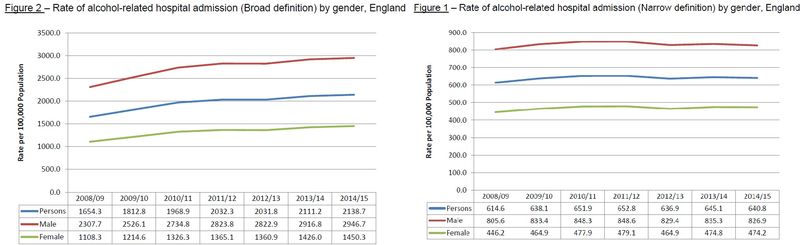

Alcohol-related hospital admissions have been rising steadily over the last decade or so, but the latest LAPE release suggests the effect of falling consumption since 2004 may now be beginning to show. Interpreting the data is however a rather complex issue, not just given variations amongst age groups and regions, but owing to the number of ways the data is recorded and measured.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions have been rising steadily over the last decade or so, but the latest LAPE release suggests the effect of falling consumption since 2004 may now be beginning to show. Interpreting the data is however a rather complex issue, not just given variations amongst age groups and regions, but owing to the number of ways the data is recorded and measured.

The historical ‘broad’ measure of admissions, which includes a proportion of admissions that are linked to but not directly caused by alcohol (known as ‘attributable fractions’), still increased overall – up by 1.3% in 2014/15. However in 2014 a change of focus to a new ‘narrow’ measure of alcohol-related admissions based on just alcohol-related primary diagnoses was introduced, reportedly to give a more sensitive representation of actual changes. Under the narrow measure, alcohol-related admissions fell by 0.7%, which PHE report as ‘largely unchanged’ on last year.

A stronger downward trend in alcohol-specific admissions in under 18s continued with an 8.6% fall in 2014/15, likely to reflect the more acute nature of younger people’s admissions and falls in drinking amongst younger people. Admissions are also falling in the under 40s, but rising in the over 65s. An IAS blog post by Dr Tony Rao, a Consultant Old Age Psychiatrist, attributed this to the ‘baby boomer’ effect, with at least one-in-four alcohol-related admissions aged 65 and over.

Whilst overall rates of alcohol hospital admissions may be plateauing out, admissions specifically for alcoholic liver disease continue to rise – up 3.4% on last year and 33% up on 2008/09. This may reflect a longer lag effect than general alcohol-related admission rates, with advanced liver cirrhosis typically taking many years to develop.

A new measure of alcohol-related cancers has also been introduced, showing a gradual upward trend in the rate of alcohol-related tumours over the past decade, also likely to have a longer lag period than majority of alcohol-related conditions.

Less in the news?

Total alcohol-related admissions for England under the broad measure reached over one million in 2009/10 with subsequent annual releases generating widespread national media coverage. Indeed alcohol-related admissions had doubled in the period of 2003 – 2009 alone. This year some media reports mainly covered the increase in older people’s admissions, whilst some local press in the North East picked up on it being the only region to have shown a significant decline of 5%. The North East though still has the highest rates in the country, which may be part of the reason why it may prove to be the first to set a future trend. The region also still has a dedicated alcohol office seeking to support effective alcohol strategy.

Complexities aside, a future downward trend in overall alcohol-related hospital admissions looks likely as the effect of many years of pre-2004 rising consumption wears off. However there are signs that the trend of overall declining alcohol consumption that began in 2004 may also be about to end. The forthcoming minimum unit pricing ruling could also prove to be another important development for the future of consumption and harm figures.

Blog: The ‘Baby Boomer’ effect of increased alcohol-related harm

Older people represent an increasing proportion of alcohol-related hospital admissions, argues Dr Tony Rao

Older people represent an increasing proportion of alcohol-related hospital admissions, argues Dr Tony Rao

On 4 May 2016, Public Health England published its annual statistics for alcohol-related hospital admissions for England. Although we have usually associated the public health consequences of alcohol misuse with younger men, we have begun to see a very different picture emerge over the past decade.

Between 2001 and 2014, alcohol-related death rates in the England reduced significantly in men below the age of 60, with a corresponding significant increase in both older people men and women. For example, in men aged 70–74 and 80–84, there was an increase of more than 150%. The actual number of alcohol-related deaths in England between 1994 and 2014 increased by 65% or more in all age groups for both men and women. In the older age groups (aged 60 and over), the increase was considerably more over this 20-year timeframe. For older men, it was 117% and 82% for older women, with both of these groups showing a higher increase than the general population.

The recent data from Public Health England, as part of their Local Alcohol Profiles, paints a very similar picture. Overall, the number of alcohol-related admissions for the whole of England has increased by 32% between 2004/05 and 2014/15. For admissions that are wholly attributable to alcohol, this figure rises to 36%.

So where do older people figure in these datasets? The results might surprise you. During 2014/15, older men aged 65 and over formed 29% of alcohol-related admissions to hospitals in England. For older women, it was 26%. In other words, at least one-in-four alcohol-related admissions were for people aged 65 and over. Perhaps something else that might surprise you is that for people aged 65 and over, admissions were over 40% higher for mental and behavioural disorders associated with alcohol use compared with alcohol-related liver disease.

Last year, I looked at changes in drinking patterns in different age groups. What I found is revealing to say the least. For drinking frequency over the past week, the 16–24 age group showed a 23% reduction between 2005 and 2013 in both males and females. For those people aged 65 and over, there was only a 2% reduction for males and a 9% increase for females. For those drinking alcohol 5 days or more during the week, there was a reduction of 79% in males and 54% in females for the 16–24 age group. The corresponding reduction for the 65 and over age group was 8% in males and 5% in females. Lastly, for those 16–24 year-olds drinking above daily limits on the heaviest drinking day, there was a 35% reduction for males and a 32% reduction for females between 2005 and 2013. Over the same timeframe, there was an increase of 11% for males and 19% for women.

So what are to make of all this new data? Well, for one thing, a cause for concern for the public health and clinical implications of older people now being less likely to change their drinking behaviour than younger people is now beyond reasonable doubt. Older people also now form a sizeable proportion of alcohol-related deaths and hospital admissions.

The bottom line is that we need to pay close attention to drinking in people. There is still undoubtedly a ‘Baby Boomer effect’ of increased alcohol-related harm in older men and women. Although we are beginning to see pockets of activity around the country in addressing this trend, we have a still some way to go in providing integrated care at a clinical level for a problem that will continue to weigh heavily on the public health of this country.

Originally written for IAS Blogs.

Maxxium UK Sourz advert cleared by watchdog

Maxxium UK Sourz advert cleared by watchdog

ASA UK rejects case against #worldofcolour YouTube video

A complaint made by Alcohol Concern over an online advert for shot brand Sourz has been cleared of wrongdoing by the Advertising Standards Authority.

Seen on 28 January 2016, the ad featured “vibrant scenes” that included a fairground ride, robotic toys and a clown, under the slogan: “Sourz presents #worldofcolour… The world is full of colour you just have to go find it”.

In response, Maxxium UK said the video was “designed to highlight varied and colourful scenes from around the world”, adding that it did not show alcohol being consumed or linked with the activities shown.

The group also added that the activities were “undertaken and enjoyed by adults of all ages.”

Alcohol Concern challenged whether the ad was socially irresponsible, accused Maxxium UK of linking alcohol with dangerous, brave or daring behaviour, being likely to appeal to people under 18 years of age by reflecting youth culture, and showing people under 25 years of age playing a significant role.

The ASA ruled the advert did not breach any alcohol advertising regulations in the UK and rejected Alcohol Concern’s three separate complaints.

The watchdog stated the activities depicted would be interpreted by viewers as “playful” as opposed to “daring”, while the featured items could be enjoyed by people of all ages when viewed in a “wider context”.

Cheap alcohol behind steep rise in UK teen poisonings

Alcohol-related incidents among 15–16-year-olds doubled over 20 years

The number of teenage poisonings over the past 20 years in the UK has risen sharply, particularly among girls, according to a new study by researchers at The University of Nottingham.

The study – published online in the British Medical Journal’s Injury Prevention – also reveals that those teenagers living in the most deprived areas of the UK are 2 to 3 times as likely to poison themselves compared to teenagers in the least deprived areas.

Recognising that most evidence on the incidence and risk factors for poisonings is restricted to data on hospital admissions or emergency care visits, the researchers instead reviewed anonymised general practice records submitted to the UK Health Improvement Network database between 1992 and 2012 on poisonings for more than 1.3 million 10 to 17-year-olds.

Recognising that most evidence on the incidence and risk factors for poisonings is restricted to data on hospital admissions or emergency care visits, the researchers instead reviewed anonymised general practice records submitted to the UK Health Improvement Network database between 1992 and 2012 on poisonings for more than 1.3 million 10 to 17-year-olds.

They then calculated the incidence rates per 100,000 person years – in other words, the number of poisonings occurring in 100,000 young people in a year – for all poisonings; intentional poisonings; unintentional poisonings; those of unknown intent; and alcohol related poisonings, broken down by age, sex, calendar period and level of socioeconomic deprivation, as measured by the Townsend Index (illustrated).

In all, there were 17,862 cases of poisoning among teens between 1992 and 2012. Overall numbers of new cases of recorded teen poisonings rose by 27% between 1992 and 2012, from 264.1/100,000 person-years to 346.8/100,000 person-years.

The largest increases seen during this period included alcohol-related poisonings among 15–16-year-old girls, which roughly doubled.

“Between 2007 and 2012 almost two-thirds (64%) of poisonings were recorded as intentional, with only 4% unintentional. Some 16% were related to alcohol, while the intent was unknown in 16% of cases” said research leader Dr Edward Tyrrell from the University’s Division of Primary Care.

Dr Tyrrell noted a clear divide between the sexes, stating that the rate of poisoning in boys/young men was less than half that in girls/young women. This was reflected in the rate of alcohol-related poisonings, which were 10% lower in boys/young men.”

The study concludes that overall rates were strongly linked to socioeconomic deprivation, with those from the most deprived areas 2 to 3 times more likely to have a poisoning than those from the least deprived areas.

Dr Tyrrell stressed some of the findings’ caveats. This included potential confounding factors contributing to the increasing rates among young women, such as increased health seeking behaviour or changes in GP coding practices, or popular trends, such as clinicians perceiving intentional poisonings as more frequent and therefore recording events as such.

“One potential explanation for the increase in alcohol poisonings over time is increased availability, with the relative affordability of alcohol in the UK increasing steadily between 1980 and 2012, licensing hours having increased since 2003, and numbers of outlets increasing alongside alcohol harm,” he said.

He added: “Since intentional and alcohol-related adolescent poisoning rates are increasing, both child and adolescent mental health and alcohol treatment service provision needs to be commissioned to reflect this changing need. Social and psychological support for adolescents should be targeted within more deprived communities to help reduce the current social inequalities.”

First-ever conviction of below cost alcohol vendor

Adapted from the Local Government Lawyer

A Gateshead shopkeeper has been prosecuted for selling alcohol below the minimum price in what is thought to be the first case of its kind under the Licensing Act 2003.

Ahtsham Ghafoor was found guilty at Gateshead Magistrates’ Court on four charges relating to the sale of ‘Kommissar Vodka’, which he was selling at less than the cost of the duty and VAT payable on it.

The Government introduced the ban on ‘below cost’ selling on 28 May 2014, in a bid to tackle the worst examples of sales of cheap alcohol, making it an offence to sell any product at less than this price floor. It was added to the licensing conditions of the Mandatory Code of Practice, meaning that failure to comply with the permitted price condition may be an offence under section 136 of the Licensing Act 2003, subject to the maximum punishment of an unlimited fine and / or six months in prison. It may also result in a review of the licence, or the service on the premises of a closure notice under section 19 of the Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001.

Under the legislation, the minimum legal price for a bottle of 37.5% ABV vodka would be £8.89 but Ghafoor was selling the vodka for £7.99. Gateshead council claimed that some of the vodka being sold by Ghafoor was found to be counterfeit, and was unfit for human consumption. Ghafoor was also found guilty of selling a product that was falsely described as vodka, and of falsely declaring an alcohol content of 37.5% ABV when the alcohol content was in fact 23.3% ABV.

Ghafoor was fined a total of £3,200, ordered to pay costs of £1,331 and required to pay a victim surcharge of £120. The vodka seized by Trading Standards officers was ordered to be destroyed.

Alice Wiseman, Gateshead Council’s Director of Public Health, said: “This outcome sends a message out to licensees in our area that they must act responsibly. The harm that can be caused by cheap alcohol is massive. Retailers need to think about the impact of their actions.”

Sue Taylor from Balance – the North East Alcohol Office – said: “We welcome the guilty verdict in this case and commend the work of the local authority in identifying alcohol sold at a price contravening the ‘below cost’ ban. At the same time, the ‘below cost’ ban is nowhere near as effective as the introduction of a minimum unit price for alcohol, which would help to protect young people and dependent drinkers in communities across the North East.”

Strong legislation needed to minimise alcohol harms

Paper claims governments have failed to take on industry for the good of public health

A group of leading experts, including Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, have published an article warning that booze does not just harm the health of drinkers but also has knock-on effects on the general population.

The authors of “Alcohol: taking a population perspective” write that, although an unlikely prima facie topic for the Nature Reviews journal, the wider harms of alcohol to health are increasingly being dealt with by gastroenterology and hepatology physicians, and that as one of the major threats to the country’s public health, the health harms from alcohol require concerted policy action at a national level.

The authors of “Alcohol: taking a population perspective” write that, although an unlikely prima facie topic for the Nature Reviews journal, the wider harms of alcohol to health are increasingly being dealt with by gastroenterology and hepatology physicians, and that as one of the major threats to the country’s public health, the health harms from alcohol require concerted policy action at a national level.

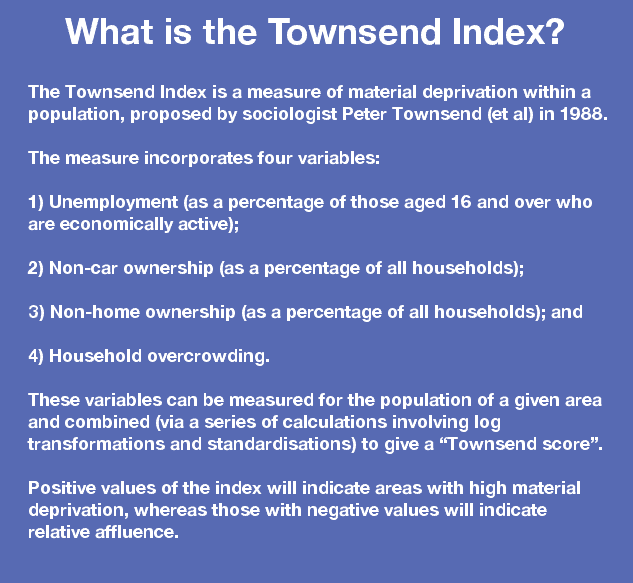

They observed how the UK has seen a marked increase in consumption from relatively low levels compared with its neighbouring European countries such as France and Italy (figure 2 from article, illustrated), and that a population-level approach to public health would not only emphasise the fact that alcohol harm is not just about a small minority of dependent drinkers, but also that the cumulative harm in those consuming alcohol who are not considered ‘problem drinkers’ is a huge problem that will be missed without a population perspective.

Strong evidence exists for the effectiveness of different strategies to minimise this damage and those policies that target price, availability and marketing of alcohol come out best, whereas those using education and information are much less effective.

Yet, the authors remarked, “our governments are either insufficiently bold or too influenced by the alcohol industry to follow the evidence on these key issues”.

When they do, they have been able to pass strong and effective legislation, such as minimum unit pricing in Scotland.

But while clinicians wait for their governments to adopt the strategies needed to improve public health standards, the authors advise that they themselves will need to become public health advocates for the populations they serve as well as for their patients.

Majestic Wine boss calls for minimum pricing

Discount retailer adds its name to calls for legislation. Adapted from Buzzfeed

The boss of one of the UK’s biggest drinks sellers has made an unexpected call for the government to introduce minimum pricing on alcohol, in line with recommendations from doctors and campaigners.

Rowan Gormley, chief executive of Majestic Wine, said he was in favour of the measure and warned that too many young people were loading up on alcohol before heading out for the night.

He told BuzzFeed News: “We’d be in favour of a minimum unit price for alcohol. What happens now is if kids are going out to the pub, they make sure they’re pissed before they go because they can’t afford to drink in the pub. They buy a cheap bottle of something and drink it in the car park beforehand.

“Just look at the rise in alcohol-related crime and accidents and injuries, and all the rest of it and where it’s happening. It’s kids going out, buying cheap alcohol, and causing problems. I think it’s something that should be looked at.”

In 2013/14 victims of violent attacks believed the offender(s) to be drunk in 53% of incidents – or 704,000 offences – while 29% of all violent incidents took place in or around a pub or club, according to Alcohol Concern.

Minimum unit pricing would make cheap ciders, spirits and extra-strength beer more expensive because of their high alcohol content.

Gormley also accused supermarkets of being irresponsible in selling bottles of wine and beer at “below cost” to entice shoppers into their stores. Last Christmas, Morrisons said its sales had improved thanks to it cutting its beer and wine prices. Analysts have privately suggested this meant bottles and cans were being sold at a loss to encourage shoppers through the doors and flatter the figures.

“It is rife and a big way for supermarkets to pull in customers,” he said. “It’s a very effective way of winning over middle England with discounted Rioja, who then come in and buy sun-dried focaccia with olives and rosemary, which has a 90% profit margin on it.”

Champagne has also been a particular battleground for supermarkets – with some offering bottles for as little as £7.50 – especially with Aldi and Lidl attempting to take a chunk of the market.

But Gormley said it was impossible to make a bottle of champagne for that.

“The supermarkets sell a basket of other stuff, so they’re quite happy to take a loss on the wine,” he said. “I think it is a big thing. I saw one supermarket offering champagne at £7.50 the other day.

“Champagne costs at least £11 a bottle to make, so there’s no way they’re making a profit on it. They’re definitely not doing that to make money, they’re doing it for another purpose.”

Although passed by the Scottish government four years ago, the implementation of minimum unit pricing is currently on hold due to a legal challenge led the Scotch Whisky Association. The Scottish courts are due to make a decision on the case later this year.

Online alcohol marketing is “unavoidable”

Adapted from Reuters Health

Adolescents in Europe may be just as susceptible to online alcohol marketing as their counterparts elsewhere, according to a recent study in four countries that links the ads with kids’ likelihood of drinking and of binge drinking.

There have been similar results from studies conducted in the U.S., Scotland and the Pacific, said lead author Avalon de Bruijn of the European Center for Monitoring Alcohol Marketing in Heerde, the Netherlands, but “it was a surprise to me that the impact of online advertising was so strong and the exposure so high among young people in these countries.”

Alcohol marketing seems unavoidable on the internet, de Bruijn told Reuters Health by email.

The researchers surveyed more than 9,000 students around age 14 at schools in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. About 4,500 kids said they never drank alcohol and were categorised as non-drinkers; all others were categorised as drinkers. In addition, one quarter of all the participants said that they had five or more drinks at once in the past 30 days and were classified as binge drinkers.

The students answered questions about having seen promotional emails or joke emails mentioning alcohol brands and websites for alcohol brands or whose content was about drinking. They were also asked about using mobile phone or computer screensavers containing an alcohol brand name or logo and about having used a profile website on social media that contained an alcohol advertisement.

Two-thirds said they had noticed an alcohol ad online, and one third had used a profile website with an alcohol ad. One fourth received promotional emails containing alcohol advertisements and one in five looked at websites for alcohol brands. The proportion of kids who had downloaded a screensaver featuring an alcohol brand ranged from just under one in three in Italy to one in six in Poland.

In each country, higher exposure to online alcohol marketing was tied to greater odds of being a drinker and of binge drinking, according to the results in Alcohol and Alcoholism.

“Existing research suggests that exposure to alcohol marketing increases the risk of starting to drink and to increase the amount and frequency of drinking among drinkers,” de Bruijn said, though the current study cannot prove that one factor causes the other.

Active engagement with online marketing materials was also found to be more closely linked to drinking behaviour than passive exposure to them, the report notes.

All types of alcohol advertising have been tied in past research to higher levels of drinking, de Bruijn said. “However, the impact of online alcohol marketing is especially influential. This might be explained by the interactive and personalised character of online alcohol advertising.”

Past research has also shown that price policies and restricting the number of alcohol vendors in a certain area can reduce binge drinking among youth, she said.

Retailers: “Reducing the Strength” works – if compulsory

Research finds scheme’s effectiveness hampered by those who opt-out

Off-licences that stop selling low cost super-strength alcoholic drinks raise the prices of the cheapest alcohol in their local area, attracting “more decent customers” to their shops, according to new research. But participating retailers reported losing trade to non-participating ones, raising questions about the scheme’s limitations.

Published in the BMC Public Health (open access), researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine studied the effects of Reducing the Strength (RtS) interventions among off-licences in the two neighbouring London boroughs of Islington and Camden.

Each local authority implemented RtS independently by recruiting alcohol retailers to voluntarily remove super-strength beers and ciders (defined as cheaply sold drinks with ≥6.5% ABV) from sale in their shops, primarily with a view to reducing health and social harms associated with street drinking, but also recognising potential benefits to wider populations.

Visits were conducted between three and six months after initial retailer sign-up to the RtS scheme (intervention). 78 of the 141 off-licences in the area stocked super-strength alcoholic beverages at the start of the local authorities’ intervention. This dropped to 25 post-intervention.

RtS also made an impact among the 33 stores approached for interview that held price data, which in turn impacted on off-licences across both boroughs, among them stores selling white cider as low as 12p per unit. Despite this, the researchers recorded an overall increase in the median price of the cheapest unit of alcohol from 29p to 33p across the entire intervention area (illustrated). The absolute cheapest available unit rose only slightly due to non-participation of those shops selling white cider. Of the shops that took part in RtS (n = 22), the median cheapest available unit of alcohol rose from 33p to 43p.

Interviews of the owners of the 33 stores revealed some illuminating insights into their attitudes towards the scheme. Explaining their rationale for joining the RtS, one Camden-based owner recognised the problem of street drinking locally and acknowledged the off-licence’s responsibility for enabling such activities. But a more typical reason for participating would be to co-operate with the licensing authorities. One owner said: “We thought if we don’t do it, we’ll lose our licence – this is our bread and butter.”

The researchers also discovered that the voluntary nature of the scheme – and the knowledge that other local retailers had not signed up – reinforced the view that participation risked losing significant trade. One non-participant from Islington said: “It’s not just about us doing it. If I sign up and next door doesn’t they [customers] are just going to go there.”

Many shop owners concluded that RtS should be mandatory for all off-licences, in order to ensure a level playing field. “They should just ban the drinks… That way, they wouldn’t go to other shops… The only way to stop street drinking is to ban alcohol,” one owner said.

However, a blanket ban would contravene competition law, as it would involve retailers being coerced into joining the scheme.

Irish Public Health (Alcohol) Bill challenged in Europe

Plans for health warnings on alcohol products raise objections from member states

The newly elected Irish Government, led by the Fine Gael party, is facing opposition from several European Union countries over its plans to introduce detailed health warnings on alcohol products.

The European Commission is also reported to be concerned by the proposal, which was promised in Fine Gael’s Programme for Government.

Moves to set a minimum price for alcohol, restrict advertising and to demand health warnings and calorie counts on drinks cans and bottles were hailed as key to the raising of public health standards when approved in December 2015.

But 11 EU countries, comprising some of Europe’s biggest beer and wine producers, are worried about its possible effect on trade.

Dublin MEP Brian Hayes told Newstalk that he was concerned the intervention could delay the legislation.

“Member states must be able to react to ongoing health concerns, which are particular to those member states, in a determined and coordinated way,” he said.

“Health concerns and a proper response to Ireland’s binge drinking culture are best tackled at a local level irrespective of internal market concerns.”

The Department of Health and the Office of the Attorney General are now considering the objections, but the Government has said it remains committed to introducing this legislation despite the scale of EU opposition. Mr Hayes was quick to insist the importance of Ireland implementing its public health agenda free of interference, as part of its overarching commitment to reducing alcohol consumption in Ireland.

“The Commission issuing warning shots against Ireland on this issue denies the principal of subsidiarity and hampers public policy making in Ireland. It sets a dangerous precedent and must be opposed,” he said.

France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Slovakia, Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Poland, Romania and Spain have all raised concerns about Ireland’s Public Health Alcohol Bill, which has reached the second stage in the Seanad (the upper house of the Irish Parliament). Ireland has until the end of July to issue a response to each member state.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

How to shift the dial on alcohol policy in Europe

Florence Berteletti –

Eurocare

Anamaria Suciu –

Eurocare