In this month’s alert

George Cruikshank’s The Worship of Bacchus

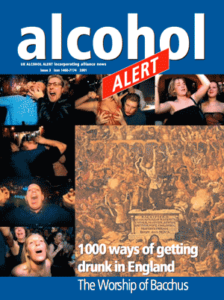

Derek Rutherford discusses the background to a re-discovered painting

Tate Britain together with a BBC documentary* has rescued from obscurity a great painting, which has not seen the light of day for almost 100 years. ‘The Worship of Bacchus’ by George Cruikshank had its first public showing in 1862 and was last exhibited in Newcastle upon Tyne from 1905-1909.

John Ruskin considered Cruikshank as “the most gifted etcher since Rembrandt”. For Andrew Graham Dixon he is “the forgotten man of British art – a giant of his time”; and of the painting, in his BBC documentary he concludes:

“Victorians didn’t like the picture; it’s not genteel; it’s not pretty; it isn’t nice. It doesn’t tell a reassuring lie about their world, but it does tell the truth about their world, an unacceptable truth about their world. For all its exaggeration, for all it’s bravado it really is the only Victorian painting that really confronts poverty and injustice and violence. And so, the reasons why the Victorians didn’t like it are precisely the reasons why it should actually last and be kept up forever on the walls of Tate Britain as a reminder of what Victorian Britain was really like.”

It took three years for Cruikshank to complete the painting. For him it was not a picture for he had not the ‘vanity’ to call it so.

Cruikshank described the picture as a map, “a mapping out of certain ideas for an especial purpose”. The purpose being to show the horrors arising from the consumption of alcohol for the whole of society. A temperance obituary to Cruikshank describes the painting as: “an eloquent protest against the drinking customs of society, and a no less eloquent – and terribly ghastly – exposition of the evils wrought on that same society by the vice of drunkenness”.

However, for art critic and public the painting was a tremendous flop. Jerrold, his friend and biographer, describes the scene in the exhibition room in Exeter Hall in 1862: “It was empty. There was a wild, anxious look in his face when he greeted me. While we talked, he glanced once more or twice at the door, when we heard any sound in that direction. Were they coming at last, the tardy, laggard public for whom he had been bravely toiling for so many years? His trusty friend Thackeray had hailed it in The Times. A great company of creditable men had combined to usher it with pomp into the world. All who loved and honoured and admired him had spoken words of encouragement. Yet it was near noon, and only a solitary visitor had wandered into the room”.

Contrast this with the success of “The Bottle” a series of eight prints which he published in 1847. Described as Zola-like realism, he charts the progressive decline of a once prosperous mechanic and his family through the introduction of alcohol to the family, unemployment, the bailiffs and impoverishment, begging, child neglect and death, domestic violence, murder and finally insanity.

Robert Upstone, in his booklet accompanying the Tate’s exhibition, describes The Bottle as a “shocking sequence of compositionally taut designs, unflinching in their realism”. Thirty years after publication a total abstinence journal wrote “the moral effect they produced has surely not been equalled since the publication of the plates of Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress”. Within weeks over 100,000 prints had been sold. They were particularly popular with the poor and dramatised at many theatres. Not only was The Bottle responsible for converting tens of thousands to total abstinence, it was also responsible for Cruikshank’s own conversion.

When he showed The Bottle to William Cash, the Chairman of the National Temperance Society, he was confronted with a crisis of conscience. Cash candidly put it to him that given his grasp of the damage done by alcohol, why was he not a teetotaller? Put on the spot, Cruikshank decided “to give his example as well as his art to the total abstainers”.

From that time Cruikshank, as converts often do, became the zealot. In the campaign against alcohol problems, he ranged himself side by side with the Total Abstinence Party. This lost him many former admirers and friends including Dickens. Whilst The Bottle inspired Matthew Arnold to compose an ode To G Cruikshank there were others offended by its implications. On the day after its publication Dickens wrote:

“I think it very powerful indeed: the last two plates most admirable .. I question whether anybody else living could have done it so well .. The philosophy of the thing, as a great lesson, I think all wrong, because to be striking, and original too, the drinking should have been done in sorrow, or poverty, or ignorance – the three things in which, in its awful aspect, it does begin.”

A view which continues to prevail is that “alcoholism comes in people not in bottles” – tackle the social conditions of people and the alcohol problem is solved. This was not the view of George, for he had experienced the conviviality associated with alcohol and drink had not become a problem until he was in middle age. He had experience of acute intoxication not chronic. For George drinking was the start of a process which did not originate in “sorrow, or poverty or ignorance”. He was a product of his age where “no man was considered a gentleman, unless he made his companions drunk”.

Speaking a short time before his death, George Cruikshank said:

“If intoxicating liquor could be taken without danger, then temperance would be a good principle; but, as it is a deadly poison and does too much mischief, the best thing is to abstain from it altogether”. It was not a view of The Times which in the week of George’s death had carried an article attacking the prejudice of total abstinence: “Temperance societies cannot but be discredited by their extreme denunciations of an article of food (intoxicating liquor) which has been hitherto valued the most highly by the most civilised and progressive races of mankind”.

If this could be written sixteen years after the first exhibition of The Worship of Bacchus, it is understandable why the picture was not a success among society’s mainstream when first exhibited.

As Robert Upstone points out the Worship of Bacchus is “teeming with figures a zealous, animated manifesto rather than just a work of art. Every section of British society is included; every element of the state, and it also shows alcohol being foisted on previously teetotal cultures of the new Empire”. A missionary taps a Hindu on the shoulder, whilst another Hindu points to the bottle in the missionary’s pocket. The painting is a dense network of vignettes. At the bottom of the painting are innocent scenes of a christening, a wedding reception and a birthday party. At the top of the picture are the factory chimneys, the breweries and distilleries with the mental asylum, prison and gallows. In the picture’s centre is the figure of Bacchus at whose feet brewers and distillers dispense alcohol to the crowds who run riot and commit horrible crimes. In the middle of it all is a man who has broken free from his strait jacket and dances on a tomb with the inscription “Sacrificed at the throne of Bacchus father, mother, sister, brother, wife, children, property, friends, body and mind”.

Cruikshank intended the picture as illustrative material for temperance lecturers who, believing that prevention was better than cure, would convince moderate drinkers to become abstainers. In the lecture he gave to the temperance worthies when launching the picture, he said:

“Although we tell where moderation begins, no one can tell where it will end I believe that I have pointed out broad, undeniable facts which will, I hope, induce all those who have not yet adopted our principles, and practices to take the matter into their most serious consideration. It is a difficult thing for a moderate drinker to understand why he should leave off his small quantity because there are others who take a large quantity If they become convinced that our principles are right, they will at once see that by abstaining themselves they will not only help to save millions of their fellow creatures from destruction, but will themselves, in all probability, have better health and longer life.” The credo of his teetotalism was most likely recorded in a speech he made in December 1849, barely twelve months after his decision not to drink.

“I believe that by nature, and from the profession that I formerly belong to, that of a caricaturist, I have as keen a sense of the ridiculous as most men. I can see clearly what is ridiculous in others. I am so sensitive myself, that I am quite alive to every situation, and would not willingly place myself in a ridiculous one, and I must confess that if to be a teetotaller was to be a milksop, if it was to be a namby-pamby fellow, or a man making a fool of himself or of others, then indeed I would not be one – certainly not; but if, on the contrary, to be a teetotaller is to be a man that values himself, and tries by every means in his power to benefit others; if to be a teetotaller is to be a man who strives to save the thoughtless from destruction; if to be a teetotaller is to be a man who does battle with false theories and bad customs then I am one. I have been a convert but a short time, not much over twelve months. I wish that I had acted upon the principle of total abstinence only thirty years ago, for if I had, I am convinced that at this time I should have been much better both in body and mind. I have experienced much benefit already, both physically and mentally. I never did sneer at or scorn the question of temperance, yet I have never thought that I should stand up as a teetotal advocate”.

Whilst this zealotry annoyed the elite of his day, it was a relevant radical agenda for those concerned with raising the lot of their fellow working men and women and who saw drink as a hindrance.

Teetotal sentiment inspired early leaders of the Labour Party – Keir Hardie, Arthur Henderson and Philip Snowden to mention a few. Indeed Keir Hardie proffered this advice to socialists on the temperance issue: “Each socialist is by his creed under moral obligation to find his greatest pleasure in seeking the happiness and good of others. The man, who can take a glass of beer or let it alone is under moral obligation for the sake of the weaker brother who cannot do so, to let it alone. To me, this matter is one of serious moment.”

Temperance had an important place on the political agenda. It was part of the radical reforms needed to improve the lot of working men and women. In 1872 Josephine Butler described temperance people as “abstainers, steady men, and to a great number members of chapels and churches, and many of them are men who have been engaged in the anti-slavery movement and abolition of the Corn Law movement. They are the leaders of good social movements, men who have had to do with political reforms”.

Richard Cobden, the leader of the Anti Corn Law League in 1849 wrote:

“The temperance cause really lies at the root of all social and political progression in this country .. the moral force of the masses lies in the temperance movement and I confess I have no faith in anything apart from that movement for the elevation of the working classes”.

Joseph Chamberlain, speaking in 1876, said:

“Temperance reform lies at the bottom of all further political, social and religious reform. The enemies of strong drink are the friends of mankind”.

Thomas Burt, the Northumberland Miners Union leader and later to be the Father of the House of Commons was actively engaged in temperance reform from the 1860’s and in 1905 at the TUC Congress stated:

“I regard the temperance question as one of greatest social topics of the time. If democracy is to have a great future, one of the things it will have to do will be, individually and collectively, to grapple with the drink problem”.

Perhaps the resurrection of Cruikshank’s The Worship of Bacchus might encourage social historians to recognise the contribution of the 19th century temperance movement to the great improvements which took place in the conditions of the working men and women in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Perhaps too it might have some lessons for those who determine alcohol policy today. It may remind present politicians of all parties that it was the drinking patterns of 19th century England which gave rise to licensing law, not the other way round as the present Government and other proponents of twenty four hour drinking would have us believe.

At the commencement of the BBC documentary ‘A 1000 Ways of Getting Drunk in England’ a shot is shown of the Bigg Market in Newcastle on a Saturday night crowded with youngsters whose aim is to ‘get smashed’. England’s long love affair with drink and drunkenness continues.

*1000 Ways of Getting Drunk in England BBC Television Narrator Andrew Graham Dixon Producer Nicky Pattison

The Worship of Bacchus in Focus Robert Upstone TATE Publishing

The painting The Worship of Bacchus by George Cruikshank is exhibited at Tate Britain.

Drink, drugs and thugs

In August the National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) released their latest figures on football hooliganism in English and Welsh football*. The figures showed that, despite the greatly improved situation inside football grounds, there has actually been an increase in football-related violence overall. Patterns have changed, however, and rather than the vicious scenes of rioting fans inside stadia that were commonplace in the 1970s and 1980s almost all the trouble now appears to be taking place well away from football grounds. According to the NCIS, which monitors football hooliganism in England and Wales, the number of arrests for football-related offences went up from 3,138 in 1999/2000 to 3,391 for the last football season – an increase of 8.1 per cent. Of those arrests 85 per cent were as a result of disturbances that took place away from grounds in town centres and railway stations and in the vicinity of pubs.

This apparent increase in football related crime and violence has again sparked a debate about the nature of so called football hooligans. The debate centres on whether it is really a football related problem or in fact part of a culture that already exists in the UK irrespective of any association with football. In answer to her demand of what the FA were going to do about hooligans, a former chief executive of the Football Association once said to Margaret Thatcher: ”When are you going to get your hooligans out of my stadiums?”

Steven Powell of the Football Supporters Association has pointed out that the figures on football violence are actually a reflection of a wider problem in English and Welsh society – a problem of drunken, thuggish behaviour and not necessarily a problem unique and exclusive to football. In a debate on BBC On-line he commented, “You can see the same sort of violence that has become associated with football on a Friday or Saturday night in any town centre and it is something that we as a society have to deal with.”

This is a view shared by many other members of the public. Again to quote from a BBC On-line discussion, “The worst offenders, Newcastle, had 40 arrests all season, out of 1 million fans who attended games. I suspect that more than 40 people are arrested every Saturday night in any medium sized town anywhere in the UK. Rather than hammering the football clubs, perhaps this suggests a slightly wider problem?” A log of all incidents compiled by the NCIS has actually shown that pubs and drink persist in being a common feature of where and why trouble occurs.

The link between alcohol and football violence is, of course, a complex question. While football fan representatives are keen to distance genuine football fans from the violent drunken behaviour outlined by the NCIS report, they are also keen to point out that there are many contexts in which alcohol and the following of football combine without such ill effects. Many commentators cite the supporters of Ireland, Scotland, and Denmark, for example, as to illustrate how countries with similar alcohol consumption patterns to England do not have the same degree of associated violence. This again reinforces the argument that there are wider issues around the English drinking culture that need to be assessed and better understood. To break this down further, an analysis of the NCIS figures demonstrates that distinct patterns can also be ascertained within regions of England. The north-east comes out strongly from the figures as the area with the most drink related offences. Sunderland and Newcastle football clubs, for example, top the league of most unruly fans. Sunderland had 166 of their fans arrested last season and Newcastle 191. Of those, 48 Newcastle fans were arrested specifically for drink-related offences with 68 from Sunderland. The behaviour of north-east football fans contrasted sharply with that of their London counterparts where Arsenal only had seven fans arrested for drink-related offences, followed by Charlton Athletic with six. Overall, Leicester City has the best record with only two fans arrested last season for drink-related offences. So further analysis and research is required to ascertain precisely what the figures say about the English, if not British, drinking culture and within that what the indications are for regional variation.

The problem of football-drink related hooliganism also illustrates the significance of the availability of alcohol in exacerbating violent behaviour. The modern phenomenon of evening kick-offs, designed to accommodate television coverage, has led to increased opportunities to drink before games. Peter Hilton, chief superintendent of the British Transport police said: “Different kick-off times throughout the week have made policing operations more costly and challenging.football is no longer about 3pm kick-offs on Saturday afternoons.

Television is dictating kick-off times and fans are taking days off in the week, having a drink all day and then travelling to matches. Much of the trouble is away from stadiums so we need more resources from football, which is making money from television.” In Scotland the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents (ASPS) has expressed extreme concern over later kick-off times. The ASPS Chief Superintendent Allan Shanks said such moves could lead to an increase in city centre violence, ”supporters will have longer to consume alcohol before the kick-off and when they come out of the ground at about 19.30 there is the potential for them to frequent already busy pubs and clubs.” He further commented, ”we are just concerned that perhaps the commercial interests have taken precedence here”.

Overall the NCIS figures make worrying reading for both the football authorities, for whom there is still the concern that a criminal violent element is associating itself with the game, and for wider authorities, including the police, for whom these figures demonstrate that drink related violence and criminality still pose a threat. They also serve as a timely reminder to the government with its widespread relaxation of licensing laws in England and Wales that drunken, aggressive, and violent behaviour in town centres still persists and that the availability of increased opportunities to drink alcohol fuels that problem rather than diminishes it.

Alcohol affects us all

Scotland’s Developing Approach

Jack Law

It is an exciting time to be working in the alcohol field in Scotland. The Scottish Executive has begun a consultation process, seeking the views of the broad community to inform its Plan for Action on Alcohol Misuse. By the end of the year we will have a national strategic framework for tackling alcohol misuse in the form of a Plan for Action. Indeed, even the media have revived their interest in alcohol misuse and licensing law.

Why is this happening now?

It may be that the creation of a Scottish Parliament is something to do with this revitalisation in interest. The Parliament has responsibility for health and social issues which has perhaps allowed greater attention to be paid to matters relating to alcohol misuse than in the past. It appears that that we are becoming increasingly aware that the cost of alcohol misuse to society significantly outstrips the costs associated with the use of illegal drugs. In the recent debate on alcohol issues in the Scottish Parliament, it was quoted that “a conservative estimate of alcohol related deaths in Scotland is 3000, ten times the number of illegal drugs related deaths in Scotland”. Whatever the reasons, the Scottish Executive is to be commended on its decision to produce a Plan for Action.

It is clearly the case that alcohol misuse is a major social and public health issue for Scotland. For example, figures released by Greater Glasgow Health Board indicate that 30,000 males and 3,000 females weekly drink more than twice the recommended limits. We still tend to binge drink, and remain wedded to the idea that intoxication and having a good time are synonymous. One of the main problems arising from binge drinking is the strain it places on emergency services such as accident and emergency services and the police. We know that alcohol is a factor in 65%-75 per cent of violent crime (source Measures for Measures: A Framework for Alcohol Policy, Alcohol Concern, London, 1997) and that 1 in 5 of all violent crimes takes place in or around licensed premises (source Scottish Crime Survey, 1996).

Underage drinking is a cause for concern. Figures indicate that 75 per cent of fifth year pupils and 15 per cent of primary six pupils drink alcohol at least once a week (source Providing Drug Education to Meet Young People’s Needs, Scottish Council for Research in Education, 1999). Undoubtedly young people are influenced by adults’ drinking patterns, whether it is their family, friends, or by prominent rôle models (pop stars, sportsmen, DJs, etc), who can reinforce the association of drunkenness with having a good time. Indeed Scotland is similar to the rest of the UK in that young people’s consumption appears to be on the increase, and that the pattern of binge drinking is being continued by the younger generation.

In 1995 the Scottish Health Survey found that 13 per cent of women had exceeded the sensible limit, and by 1998 this had increased to 15 per cent. Alcohol consumption amongst young women appears to be on the increase. 24 per cent of Scottish women aged between 16 and 24 years exceed the weekly safe limit of 14 units (source: The Scottish Health Survey, 1998). There is an upward trend of women seeking help for alcohol related problems, inquiries to Local Councils on Alcohol by women have increased by 17 per cent over the last two years. It would appear that women in employment are now consuming more alcohol than they have in the past, and this is giving some cause for concern, particularly for the longer term.

So, what is happening in Scotland?

On 7th December 2000, in the debate on alcohol misuse in the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish Deputy Minister for Health, Malcolm Chisholm announced plans for a major inclusive consultation process, which would take place between February and the end of June. This will lead to the development of an alcohol misuse strategy, taking the form of a National Plan for Action by the end of 2001.

He also announced that there would be a comprehensive review of licensing law, undertaken by an independent committee, with a broad remit. The licensing system is one of the elements of the whole approach to alcohol misuse. The licensing review is expected to meet for about 18 months, and will draw on the overall framework set by the Plan for Action.

As progress is made towards the development of the Action Plan, we should not forget that much is already being done to address alcohol misuse in Scotland. Work on prevention and education for young people, services for those who misuse alcohol and their families and carers is ongoing. The Scottish Executive also supports the work of the Alcohol Misuse Coordinating Committees that were set up locally to ensure measures and services are in place to tackle alcohol misuse. These local partnerships involve representatives from all key interests including health, local authorities, police, licensing, etc.

At national level the Scottish Advisory Committee on Alcohol Misuse (SACAM), which brings together representatives from all key sectors, including health, local authority, police, the drinks industry, the licensed trade and the voluntary sector (including Alcohol Focus Scotland) meets under the chairmanship of Malcolm Chisholm. The committee is probably unique in the UK in that it brings together all the major players in the alcohol arena, and through its deliberations is able to draw together their common interests and concerns. SACAM was specifically set up to advise the Scottish Executive on an alcohol misuse strategy and is closely involved in advising Ministers on the development of the Plan for Action. SACAM is also involved in the development of some building blocks for the Plan, including in the area of, services provision, prevention and communication, and information collection and dissemination.

Alcohol Focus Scotland (formerly The Scottish Council on Alcohol) is actively involved in SACAM, in reviewing policy, and in addressing the breadth of alcohol related issues in Scotland. In this connection we have organised key events to bring together the accumulated knowledge and experience of those with an interest and expertise in alcohol to contribute to the consultation process for the national Plan for Action. We are also involved in services through the 28 Local Councils on Alcohol affiliated to us, which means that we cover the majority of Scotland. As well as providing high profile information on alcohol issues, we target a number of key areas such as information for people affected by alcohol misuse, training for those addressing alcohol related problems, and prevention.

We manage two national projects aimed at reducing alcohol misuse through prevention; Drinkwise and ServeWise.

The national Drinkwise campaign, which involves the Scottish Executive, the Health Education Board for Scotland and Alcohol Focus Scotland working in partnership, has developed considerably since its inception some five years ago. The campaign, which places at its core the concept of personal responsibility, focuses on sensible drinking and the exercise of personal choice through a process of cognitive reappraisal. In other words through the presentation of challenging and thought provoking images and text, the campaign aims to raise questions for individuals about their drinking, which are intended to influence their drinking behaviour. The campaign has a national dimension and a local focus through the twenty local Drinkwise organisations which run community based campaigns. Between 1996 and 2001, Drinkwise has been involved in over eighty local projects, with themes such as personal responsibility, safety, relationships, public behaviour and leisure.

ServeWise is a training programme aimed at licensees and those who sell alcohol, which has the support of the Scottish Executive. It has grown from a local project based in Aberdeen into a national initiative, aimed at training those who serve alcohol to understand their legal and social responsibilities. The training has been developed and tested with the assistance of the police, the licensed trade, licensing boards and colleges of further education. By developing such a training programme, Alcohol Focus Scotland hopes to contribute to a reduction in the number of accidents and crimes resulting from the misuse of alcohol on and in the environs of licensed premises, and to a reduction in the social and economic costs of alcohol misuse. A further benefit of the programme as it unfolds across Scotland is that it will set minimum standards for the sale of alcohol and contribute in a positive way to any changes in Licensing Law which may arise from the review. Overall the programme is aimed at making licensed premises, and the general drinking environment a safer and more pleasant experience for the community.

The programme is developing throughout Scotland, and enjoys the support of the trade, industry, retail trade, licensing lawyers, and other significant agencies.

Given that 1 in 5 people in Scotland are concerned about their own or someone else’s drinking, the role played by properly trained and accredited alcohol counsellors is a crucial one. Training volunteer counsellors for the Local Councils on Alcohol is an important aspect of Alcohol Focus Scotland’s work. We train between fifty and eighty volunteer counsellors, trained to university validated standards over two years, and just under twenty supervisors each year, who deliver counselling and supervision through the Local Councils. Furthermore we run an extensive programme of workshops on topics such as homelessness, young people, and brief interventions for those in the field with a concern about alcohol related issues.

While not being a direct service provider, Alcohol Focus Scotland received over 6,000 inquiries last year. Many of these are passed on to the Local Councils on Alcohol, but some may be dealt with directly. Our Information Section designs and delivers information materials for individuals, and organisations, as well as assembling information materials for research and other matters.

Alcohol Focus Scotland has the support of a network of twenty eight Local Councils on Alcohol across Scotland, from Orkney to the Borders. Each Local Council provides a variety of services including brief intervention, counselling, befriending, information and advice, and educational services. In addition the Local Councils are each involved in their local strategic planning processes for alcohol services in partnership with other local agencies. The importance of the services provided by Councils is considerable; for example, they provided over 42,000 counselling sessions last years, saw over 5,000 new clients in 2000, and currently have just over 300 trained alcohol counsellors.

It is an exciting time for us to be both influencing and developing the policy agenda, as well as working on the future for alcohol services in Scotland. The developing agenda provides us with the opportunity to make a difference to Scotland’s drinking traditions and behaviour.

Jack Law is the Director of Alcohol Focus

Alcohol policy and devolution in Wales

The National Assembly for Wales is primarily concerned with the development and implementation of Secondary Legislation. Consequently, some of the most contentious issues in the field of alcohol policy such as the current discussions surrounding the re-working of licensing laws have passed by the Institution in Cardiff. However, Wales has historically had the right to conduct referenda on proposals to extend pub opening hours and while they have hardly led to tighter licensing, the referenda were in a very small sense an example of devolution – local communities deciding how and when licensed premises should be regulated. It is somehow ironic therefore that this aspect of licensing, currently under review by the Westminster government, will not be examined by the Assembly nor its members given an opportunity to debate it.

At the moment the Assembly has responsibility for Education, Health and Social Services, Economic Development, Arts and Culture and Agriculture. A minister drawn from the Labour-Liberal coalition and monitored by a committee of Assembly Members heads each policy area.

To date the focus has been on seeing alcohol as purely a Health and Social Service issue. Alcohol policy has been coupled with drug abuse under the common substance misuse strategy: Tackling Substance Misuse, The Partnership Approach. Calls to develop a specific alcohol policy for Wales have been ignored. Whilst the current strategy has four themes, its principal aim is to promote education as prevention, to provide resources to treat addiction and despite its commitment to address consumption, is void of any plans to realistically tackle the level of alcohol consumption in Wales.

With its emphasis on treatment and prevention through health promotion, the National Assembly’s alcohol policy can be defined best, to borrow the worn analogy, as the ambulance at the foot of the cliff, not the fence at the top. For the Assembly administration, an alcohol problem is simply a medical condition, something that is treated. A bit like catching a cold if you are foolish enough to venture outside with wet hair.

Wales, traditionally stereotyped as country of heavy industry, non-conformist religion and rugby, currently features high in any analysis of alcohol consumption and, unsurprisingly, alcohol related harm. Formerly the twin pillars of its society, industry and religion served to contextualise alcohol consumption.

These institutions promoted distinct cultures symbolised more often than not by the chapel and the union or workingmen’s club. Communities often had a large supply and choice of both pubs and chapels often in equal measure. And whilst alcohol use was commonplace it was no more normal or common possibly than abstinence. The union or in mining communities, lodge culture also provided social guidelines and values. Alcohol use, traditionally a masculine pastime had distinct social norms and its own acceptable behaviour. Drunkenness was frowned upon even within the context of the pub or club as a sign of a lack of masculinity. The same was true of swearing and bad language. To drink a large amount was acceptable, to be drunk was not.

Similarly, the chapel exercised a strong hold on the community, and in a very practical sense provided alternative leisure and recreational activity. It also provided a worldview that lifted individuals from the everyday struggle to earn a living and enculturated its own values and norms.

It is almost a truism to point out that the demise of industry brought the death of the trade union movement. The non-conformist religion has also died and clubs, pubs and chapels have been demolished. In the case of many chapels they have been converted into bingo halls, warehouses or most recently into the latest theme pub. So if the devolved government cannot tackle the problems of chronic alcohol consumption directly we can only hope that it can do it indirectly through addressing the social and economic factors often associated with it.

The Assembly is well placed to tackle the economic and social factors that have brought social exclusion and relative poverty to Wales. But despite the establishment of the Assembly and growth in the UK economy, GDP continues to fall in Wales. The last vestige of its industrial past is disappearing and the Asian manufacturing plants have retreated with the death of their tiger economies. Such poor economic performance has however earned Wales the prestigious designation of Objective 1 status (the consolation prize for the poorest economic performance in Europe) and substantial assistance for restructuring. Following the Irish model, seven years of investment should contribute in some small way to addressing its economic decline and under achievement. One thing is true, things cannot really get much worse, and when you hit the bottom the only way is up.

However, whilst historically strong and vibrant communities built upon the twin pillars of religion and industry enabled a social order to exist that ameliorated the effect of alcohol, the promised economic resurgence alone will not provide such an antidote. In fact, a pattern is emerging where economic growth and in particular the rise of disposable income, rather than decreasing alcohol consumption, will add to the growing trend towards binge drinking. The bare fact is that the value-laden world of religion and trade unionism (today what we would call social action) has been replaced by a post eighties consumerism. The rise of alcohol as a consumer product is widely recognised and affects Wales to the same degree as other developed economies and cultures.

So the National Assembly lacks the powers to address alcohol policy directly and can only pick up the pieces. It can and arguably must play a role in rebuilding Wales’ economic base alongside Westminster in the hope that this in some way will have an effect on social exclusion and aspects of chronic alcohol consumption. In its favour, the National Assembly for Wales can be said to lack the power to act unlike those administrations that simply lack the will!

Iestyn T Davies is the Director, Welsh Council on Alcohol and other drugs

Not so happy hours

Happy hours need to become a thing of the past as part of the drive against increasing crime and disorder, says a new report from NACRO, the crime reduction charity. Drink and disorder: alcohol, crime and anti-social behaviour argues that alcohol is often a significant factor in crime and disorder. The problem needs to be seen in the context of the prevailing dinking culture in the United Kingdom, a culture which encourages bingeing and hazardous use of alcohol.

Whilst the report recognises that it is too simplistic to claim that alcohol is the cause of crimes in which it is a factor, it is inextricably involved in an alarming proportion of a wide variety of offences. “While the precise nature of the relationship between alcohol and crime remains a matter of controversy, there is abundant evidence that many crimes are committed by people who have consumed alcohol, often to excess.” The report quotes a survey of police officers carried out by Alcohol Concern which showed that 60 per cent saw alcohol as having a greater impact on their work than illegal drugs; 68 per cent said that they encountered alcohol-related crime on a daily basis; and 96 per cent believed that the scale of the problem was not accurately reflected in crime statistics.

In the context of discussing the complex subject of the causal relationship between alcohol and crime, the authors of the report make the point that it is necessary “to disaggregate the various offences believed to be alcohol-related. Much of the debate about alcohol and crime is focused on violent and disorderly behaviour[These] are not the only kinds of offences that appear to be linked to alcohol. In particular, there is evidence that a significant number of burglaries and robberies are committed under its influence.”

NACRO’s report, whilst accepting the problems inherent in establishing the causal link, has no doubt that there is “enough evidence to show that alcohol is a contributory factor in many instances of crime and anti-social behaviour.” Research shows, for example, that the victims of crimes adjudge that offenders are under the influence of alcohol in 40 per cent of incidents – “It would be perverse,” says the report, “to deny that alcohol has been a contributory factor in a significant proportion of cases.” Common sense indicates that, given the knowledge we have of the effects of alcohol, it is “reasonable to suppose that [it] can increase the chances of someone acting in a criminal or anti-social way.”

Dr Marcus Roberts, Nacro’s policy manager and co-author of the report, says:

“Alcohol enjoys a very special status in our society. From a stiff drink at the end of a busy day to the conviviality that alcohol can bring to a social occasion, many people would feel that their lives would be poorer without it.

“At the same time there is no doubt that there is a binge drinking culture in the UK, particularly among young men, and that patterns of sporadic drinking leading to acute intoxication are more strongly associated with violence than frequent moderate drinking. If we are serious about reducing crime we need to give thought to how we can create a more responsible drinking culture. It’s not about prohibition, it’s about planning.”

The report makes a number of important recommendations:

- Developing alcohol treatment services for young people – they are drinking more than ever but there is a shortage of appropriate programmes for the age group.

- Proof of age cards.

- Local authorities should ensure that there are adequately managed public transport and taxi services and that late-night eating places are appropriately situated to avoid creating flashpoints for violence.

- Pubwatch schemes which improve communication between publicans and the police. A Sheffield scheme provided bar and door staff with pagers to provide police with early warning of potential disorder problems. An evaluation of the scheme showed a fall in alcohol-related crime.

- Strengthening the law so licensees are held responsible for injury or damage caused by a customer who has been served too much alcohol as a result of the licensee acting negligently.

- Training for door staff to identify potential troublemakers.

Celtic myths – the challenge for Ireland

The myth of the perpetually drunken Irishman is in danger of becoming reality. This was the stark message of Dr Anne Hope, Advisor on National Alcohol Policy at the Department of Health of the Republic of Ireland

Dr Hope was speaking at a conference held in April at Croke Park, Dublin, the home of the Gaelic Athletic Association. The conference was organised by Dothain, the group founded by Dr Michael Loftus to combat alcohol problems, and Eurocare. Professionals and volunteers from across Ireland attended, interest and concern heightened by the recently published figure which showed dramatically increased consumption in the Republic, particularly among young people.

One of the aims of the conference was to explore the possibility of setting up a non-governmental organisation (NGO) for Ireland which will lobby for measures to combat the problems arising from alcohol consumption. The vibrant economy of today’s Ireland means that there has been a considerable increase in disposable income. Dublin is a lively, cosmopolitan city with a bar or restaurant on every corner. Every night the streets are full of young people enjoying themselves in the atmosphere of national success. The downside of this scene is the spiralling incidence of alcohol-related violence, accidents, and disorder.

Dr Hope, in addressing the Croke Park Conference, drew attention to prevalent drinking patterns. The figures she presented show that in many ways the drinking habits of the Irish are becoming more like those of people in the United Kingdom. In other words, there has been a marked increase in binge drinking. What is also alarming is the indication that young women are matching young men drink for drink, with all the consequent dangers.

The recently published ESPAD report (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs) further underlined the scale of the problem. It showed that, of Irish 16 year olds, only 8 per cent classed themselves as non-drinkers, whereas 32 per cent of both boys and girls, reported three or more occasions of binge drinking a month.

The economic cost of alcohol-related problems was enormous, said Dr Hope. Estimates of health care costs suggested a figure of £220 million, whilst road accidents accounted for another £248 million. Absence from work cost the Irish economy £736 million per annum with an additional £100 million in lost taxes.

Money is, of course, secondary to the human cost. Dr Hope showed the alarming trend in alcohol-related deaths, other than in motor accidents which had fallen since 1990. Deaths from falls, suicide, and cirrhosis had all increased over the same time period.

Dr Hope’s role as advisor to the Irish Government on alcohol policy means that there is a drive towards minimising the problems which are in danger of making the national stereotype a national disaster. It is necessary, she said, to regulate availability, control promotions, enforce deterrents, provide treatment and education, and encourage alternatives.

Although strides are being made in some directions, Ireland is facing the same tendency towards deregulation as other European countries. Longer opening hours were introduced by the Intoxicating Liquor Act of 2000. There was in operation an alcohol price freeze. These combined with the increased wealth of the nation, and especially the disposable income of young people, to make counter-measures all the more urgent.

Dr Hope summed up the challenges that lay ahead in Ireland. There was hope that the population was increasingly aware that the level of alcohol consumption played an important and detrimental part in public health. Hard decisions faced the Government and it was important that public support was mobilised to make these politically realisable. It was vital that best practice was shared – hence the importance of the establishment of an NGO which could help co-ordinate efforts and make representations to Government – and that evidence-based research was developed. Ireland needed to work within the European Union and the single market in order to foster integrated strategies which would be effective.

If Ireland is not to be personified by the familiar image of Brendan Behan carousing towards the grave, then action is needed now. The message to come out of the Croke Park Conference was one of determination.

The numbers game

The number of drug dependent people has doubled since 1993. This trend emerges from data published by National Statistics in Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults, 2000.

Indication of drug dependency in 2 per cent of women and 5 per cent of men produces a figure of about 2 million people in England and Wales. The dependence rate was highest among those aged 16 to 24 years of age: 8 per cent for women and 16 per cent for men.

Dependence on cannabis was the most common followed by ecstasy and amphetamine.

As far as use of illicit drugs is concerned, 8 per cent of women and 13 per cent of men reported using them during the past year. Among the 16 to 24 year olds, the figures were 26 per cent of women and 34 per cent of men. In the case of cannabis, particularly relevant in the context of the current debate on legalisation, the percentages were 25 for women and 33 for men.

As with illicit drugs, hazardous drinking was more common among younger people: 53 per cent of 16 to 24 year old men and 30 per cent of women. According to the report “mild to moderate alcohol dependence was also more common in the younger age group but the few cases of severe dependence were found in those aged over 30”. Overall, 26 per cent of those questioned reported hazardous levels of drinking and of these 7 per cent showed symptoms of dependence on alcohol. Men were much more likely than women to drink in this way: 38 as opposed to 15 per cent.

National Statistics have also produced Drinking: adults’ behaviour and knowledge in 2000. It emerges from this report that many people are still uncertain about units and that daily benchmarks are having little effect.

There was a strong association with age. “Younger respondents were more likely to know about alcohol units than were older people: 82 per cent of those aged 16-24 had heard of alcohol units, compared with only 62 per cent of those aged 65 and over.” This is not surprising, given that young people, on average, drink more than older people and knowledge of units is related to alcohol consumption. In all age groups heavier drinkers were the most likely to have heard of measuring alcohol in units.

Overall, those groups most likely to know about units were women, younger people, those from non-manual social classes and higher income earners, and moderate or heavy drinkers.

It is also important that people know the alcohol content of the particular drinks they consume. In 2000, 50 per cent of those who had drum beer in the last year were aware that a unit was half a pint. One in five, however, got it wrong, the most common misconception being that a unit of beer was a pint. Nearly a third of beer drinkers had either never heard of units or were unable to say what a unit of beer was. The report says that awareness of the “alcohol content of wine and spirits was a little higher: 58 per cent of wine drinkers knew that one glass was a unit of wine and 60 per cent of those who drank spirits were aware that a single measure was one unit”.

There has been a steady increase in the percentage of those who know about daily benchmarks from 54 per cent in 1997 to 58 per cent in 1998 to 64 per cent in 2000. This, of course, suggests that a third of the population is unaware that drinking 4 or more units a day for men and 3 for women is not recommended. Knowledge of the benchmark’s existence means that people were aware of what they actually were. 45 per cent of respondents “could not attempt an answer to that question”. Ironically, the largest proportion of those who knew about daily benchmarks consisted drinkers who exceeded the limit. This may suggest that benchmarks are having little effect in educating people to restrict their drinking to recommended levels.

Ain’t life a drag

In the current debate about legalisation, decriminalisation or de-penalisation of illicit drugs, many advocates of reform assert that our present system of control, based on the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and its various amendments, is a failure and should be abandoned.

Here, John Ramsey and Lindsay Hadfield challenge this view, and identify a number of pitfalls in the case for legalisation that its proponents normally choose to ignore.

Ain’t Life a Drag

We already have three legal social drugs: tobacco, alcohol and caffeine. Use of the last is of little health consequence but alcohol causes considerable damage to some users and tobacco harms a large proportion of the people who use it – 50 per cent of tobacco users will die as a result of the habit.

It is often proposed that the illicit drugs which, it is argued, are no more harmful than our social drugs should be legalised, since a criminal conviction does more harm than the drug itself. This argument is used particularly for cannabis, often for ecstasy, and usually by middle class people least likely to be harmed by the drugs.

It takes no account of the vulnerability of the more socially disadvantaged who experience most of the problems associated with drug use.

We suggest a better course would be ensure that the law does not do more harm than the drugs and to do all we can to stop the use of tobacco and reduce the harm associated with alcohol. But it would be criminally negligent to make another drug administered by smoking more freely available.

The widespread and almost universal use of ecstasy at dance clubs (some surveys suggest 80 per cent of attendees had taken ecstasy that evening) is taken as a reason to legalise it and so prevent the harm caused by the illicitly produced, supposedly contaminated drug.

There is little serious pressure to legalise either heroin or cocaine (or crack) although it is often suggested heroin should be prescribed to addicts.

We consider the practical difficulties associated with these proposals.

Cannabis

The Dutch de facto legalisation experiment where “Coffee Shops” are allowed to sell small quantities of cannabis openly was adopted in order to separate soft drugs from hard, allowing cannabis users to buy and smoke cannabis without coming into contact with dealers of hard drugs. They claim to have broken the link between the supply of cannabis and the supply of hard drugs (heroin and cocaine). The law has not been changed; it is just not enforced. The sales of soft drugs are not prosecuted under certain conditions.

The coffee shops are required not to:

- advertise

- sell hard drugs

- cause public nuisance

- admit minors (under 18)

- sell large quantities, more than 5 grams per transaction

- sell alcohol

In addition local rules may also be applied:

- no parking outside coffee shops

- close at 10.30 p.m.

There were 1,200 coffee shops in 1995 (1 per 10,000 inhabitants) but this had reduced to 846 in by 1999. Most offer a wide range of hashish and marijuana products from different countries and of varying strengths but as the supply has not been legalised the coffee shop owners still have to buy on the illicit market.

The Dutch have employed their horticultural skills to grow cannabis products illegally and develop exotic high strength cultivars (Netherweed).

It seems unlikely that if we were to adopt a similar approach British retailers would be free to purchase drugs from illegal sources. Could the UK government really condone an industry that necessitated the transgression of our various international obligations with regard to trafficking in illegal drugs? Would we develop our own cannabis cultivation industry? It would have to be of a substantial size to meet the demand. However our climate is better suited to growing hemp for fibre rather than drug production so the quality would be poor and security impossible unless it was grown under glass, in which case it would be expensive.

We would therefore need to establish legitimate overseas suppliers otherwise retailers would inevitably be tempted to turn to the black market to supply the exotic sounding Nepalese temple balls, Thai sticks, Pakistani Black, and Skunk.

Could the legitimate outlets compete successfully with the illicit market? Probably not. The Dutch coffee shops charge £1.5 – £7 (5 to 25 guilders) per gram, the current UK street price (untaxed) is about £1- £5 per gram. Would the legitimate suppliers of cannabis sell a comparable product at lower prices than the black market? If not, would consumers pay a premium to get their drug from legitimate sources? It seems unlikely. The evidence with tobacco and alcohol is that increasing numbers of consumers are prepared to go to great lengths to avoid paying duty.

Moreover, the price differential between legal and illicit supplies would be increased by the need of the legitimate suppliers to include overheads such as the cost of insurance required to protect them and the producers from claims from aggrieved consumers who have been involved in accidents or suffered ill health. Cannabis has the potential to cause most of the health consequences of tobacco use plus the additional risks associated with intoxication, motor impairment and psychosis.

Would the tobacco industry, which in the US is facing “class action” suites for the health consequences of its current products, take on a new product with similar or even more severe health consequences? It might, because it seems probable that freer access to cannabis would lead to more nicotine addicts and more tobacco consumption.

There is also the question of who we should allow to retail cannabis – tobacconists, off-licences, pubs, coffee shops, supermarkets, pharmacists? Some recent advocates of legalisation naively assume that sales could be controlled so that the drug would not be more widely available than at present – the only difference would be that the sources would be legitimate. But the current suppliers – dealers – are in business to make money. And just as the current suppliers are interested in expanding their markets, so legal commercial suppliers will want to maximise their profits by developing their markets, even if advertising/sponsorship is not permitted. As discussed above, there will be significant costs in establishing legitimate sources of cannabis, so any commercial producer will have to price the product accordingly. They get the price wrong, the illegal suppliers would continue to flourish.

Deliberate confusion with medical use of cannabis.

Another argument put forward is that cannabis should be legalised so that it can be used for medical purposes. It seems likely that the clinical trials of cannabinoids currently in progress in the UK will show benefits for some medical conditions. This may well lead to licensed medicines derived from cannabis. However they will not be smoked and are unlikely to be at doses sufficient to cause a high. It is perfectly consistent to licence the medicinal use of cannabinoids while prohibiting the recreational use cannabis.

Ecstasy

The problems associated with legalising synthetic drugs such as ecstasy (MDMA etc.) are even greater. The drugs have never been manufactured by the modern pharmaceutical industry and so have not undergone any safety evaluation.

Presumably the Government would insist on the same safety checks on recreational drugs that the pharmaceutical industry currently performs on medicines. This is likely to cost millions of pounds for each compound.

Evidence from the dance/club scene shows that MDMA causes a small number of deaths (probably about 90 to date in the UK). Research also indicates that MDMA causes brain changes, the functional consequences of which remain unclear, but may manifest themselves as poor memory or depression. Acceptable safety and side effects are based on a risk benefit analysis. As a society we will tolerate a drug that makes us sick and our hair fall out if it is to treat cancer but not if it is to cure a headache. What level of side effects would we accept for a recreational drug?

It is difficult to see how legalisation could reduce the mortality associated with ecstasy. This is often precipitated by personal behaviour or the ambient environment in the venue. Users argue that legalising ecstasy would ensure a consistent unadulterated product and this would improve safety. In fact, almost all the known harm from ecstasy is caused by the pure compound MDMA. There is no good reason to believe therefore that legal escasy would be any safer. Moreover, there is little evidence that the harm is strongly dose related, which means that harm can be caused by “moderate” as well as “excessive” use. With greater numbers using the legitimate, but equally unsafe, product, the total number of fatalities would probably increase. Who would be held responsible, and liable? Just the consumers themselves? Perhaps, but the legitimate pharmaceutical industry will would have to think long and hard before taking on the manufacture of MDMA for recreational use. The exposure to third party risk is high and the ethics at least questionable.

Conclusions

Freer access to drugs will inevitably lead to greater use. Current users would use more freely. Many potential users who are currently deterred would feel free to start. This is especially true for ecstasy – uncertainty about the illicit product would be replaced by confidence in government approval. Use of the newly legalised drugs would become normalised and would inevitably lead youngsters to seek other illicit thrills supplied by the black market. The widespread use of GHB, ketamine, poppers (alkyl nitrites) and a legion other drugs on the club scene supports this fear.

The question is – does the law cause more harm than the drug? So the issue becomes just how seriously we should regard these offences. Let us change the law as suggested by Baroness Runciman. Make cannabis Class C rather than Class B, and move MDMA (ecstasy) from Class A to Class B. We should also apply the law evenly across the UK and stop giving people criminal records for supplying small amounts of these drugs in private social settings. This would bring the penalties more in line with the potential harm caused by these drugs.

John Ramsey TICTAC Communications Ltd St. George’s Hospital Medical School Cranmer Terrace London SW17 0RE

Lindsay Hadfield Policy & Education Consultant Medscreen Limited Harbour Quay Prestons Road London E14 9PH

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions they represent.

Book Review – Out of It: a cultural history of intoxication

Stuart Walton Hamish Hamilton, 2001 Reviewed by Griffith Edwards

Stuart Walton is a highly experienced journalist and author of The World Encyclopedia of Wine. In the present book he ventures into areas which would not generally be seen as being within the expertise of a wine writer. Rather than dismiss the work out of hand, I started my reading with the mental set that we owed Walton a hearing. Journalists are clever people, an outside view can often be refreshing, let me not be hoity-toity about a journalist treading over my scientific home ground.

The blurb declares in bold type that intoxication is a “fundamental human right”. Well, I hadn’t thought that way before, good to be brought up sharp, I murmured. And just a few pages into the introduction, I found this statement also pretty bracing:-“the use of illegal drugs goes on relentlessly rising far from seeing this as a troubling symptom of social breakdown, I consider it a heartening and positive phenomenon.”

And toward the end of the book that same position is forcefully restated: – intoxication “is our birthright, our inheritance, and our saving grace”.

But somewhere between the beginning and end of this book, I became disaffected. Walton and I start from not all that different a position – we share the view that there can be pleasure in intoxication, that different drugs need to be differentiated, that drugs can be used without harm. I suspect also that we have in common a Millsian belief that people should be allowed to do pretty well whatever takes their fancy, provided that their actions harm only themselves and inflict costs on no purse other than their own. The dilemma of course lies in the fact that intoxication is not infrequently associated with harm, and with the costs often borne by other people.

Walton’s book substantially ignores the reality of that dilemma. His is not a tightly argued or persuasively evidenced book. Having at the beginning resolved to swear off scientific territoriality and give the chap a chance, as I read on I rediscovered the belief that there can still be some advantage in knowing what one is talking about. Broadly, Walton does not know enough, and has not thought enough to justify the position which he takes. I did not by the last page have a sense of having been intellectually challenged and that made me feel cheated. This book trivialises the social history of mankind’s relationship with drugs and that’s sad as coming from an able writer.

Podcast

Our monthly podcast features interviews with experts from across the sector.

Gambling industry harms and parallels with the alcohol world

Will Prochaska –

Coalition to End Gambling Ads