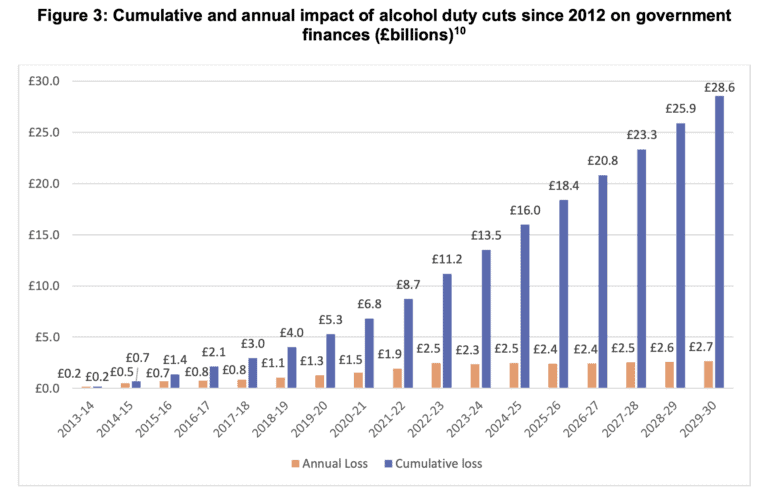

In our latest Budget Analysis, we found that cuts and freezes to alcohol duty since 2013 will cost the government over £28.6 billion by 2030.

In the Autumn Budget, Chancellor Rachel Reeves confirmed that most alcohol duty rates will go up by RPI inflation of 3.65% from 01 February 2025, making it only the third time in over a decade that most alcohol duties have been kept in line with inflation.

She also increased Draught Relief, meaning that most on-trade draught products will see reduced rates from February 2025.

As the Office for Budget Responsibility and Treasury assume that all products’ rates will go up by RPI, the decisions will cost the government £465 million over the next five years. Added to the cost of previous cuts, by 2029-30, the total cumulative foregone revenue will reach £28.6 billion. In other words, if the government had stuck to the planned trajectory for alcohol duty in 2012 – to increase all duties by 2% above inflation in 2013/14 and 2014/15, and maintain them in line with inflation every year thereafter – this would have raised another £28.6 billion for the public finances.

The Sheffield Addictions Research Group (SARG) has, for the first time, published a briefing report, modelling the likely impact of decisions taken on alcohol (and tobacco) duty at the Budget. Their analysis estimates that, compared with if all alcohol duty had been increased with inflation:

- The extension of draught relief is estimated to increase drinking, with:

- 2,167 more individuals drinking at increased risk levels

- 5,635 more at higher risk levels

- 7,802 fewer at lower risk levels

- Over five years this leads to an estimated 1,118 additional hospitalisations and 142 additional deaths.

- Alcohol duty and VAT receipts are estimated to fall by £405 million over five years.

Although increasing most products by RPI is a step in the right direction, it falls far short of undoing the damage of the past decade, with cuts and freezes significantly increasing the affordability of alcohol, contributing to an increase in alcohol consumption and subsequent harm. Therefore, IAS recommends the following:

1: Raise alcohol duty above inflation each year, targeting off-trade alcohol.

This will help tackle the rising affordability of alcohol, which has become 27% more affordable since 2012.

2: Develop a mechanism that ensures alcohol duty rates cover the external cost of alcohol harm to society and incentivises alcohol producers to reduce harm.

Current duty rates are set far too low to be able to make a significant difference to public health. Currently, the overall revenue from alcohol duty and VAT is around £15 billion across the UK – under half of the costs of alcohol to society (estimated to be at least £27.4 billion in England alone.

The government should calculate the external cost of harm or appoint independent analysts to do so in order to better inform the debate on what rates should be set at to cover the cost of negative externalities.

Each year, duty rates should increase in line with inflation or earnings. Rates should increase within days of announcement, to avoid producers forestalling.

Every 5 or 10 years, the mechanism should be reviewed to consider the latest evidence base on alcohol-related costs to society.

This would increase certainty on how duty is likely to change over time allowing businesses to plan better, and would also incentivise alcohol producers to reduce the cost of harm in order to reduce tax burden at the next review.

3: Equalise cider duty rates over time with that of beer of the same strength (ABV).

Cider is still being treated preferentially, with a rate less than half that of beer for the 3.5-8.4% ABV band, in which most common ciders fall.