Alcohol trade associations seem intent on misinforming their members, the public, and the new Prime Minister.

In numerous newspaper articles, interviews, and social media posts, both the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) and the Wine & Spirit Trade Association (WSTA) have claimed that the ‘increase’ in alcohol duty rates last August led to the Treasury losing revenue.

- On the 05 July 2024, the SWA wrote to the new Prime Minister Keir Starmer, stating that: “In the ten months since it was imposed, this tax hike reduced revenue available to HM Treasury by £108m.” In August this year they claimed the amount had reached nearly £300 million.

- And in March 2024, the WSTA claimed that: “revenue from duty receipts has declined by almost £600 million since September” due to the increase.

- Even MPs have bought this line, with Liberal Democrat Alistair Carmichael publishing the SWA’s misinformation.

To be clear, this ‘increase’ simply followed the standard assumption of the Treasury and Office for Budget Responsibility that duty rates will rise in line with RPI inflation each year.

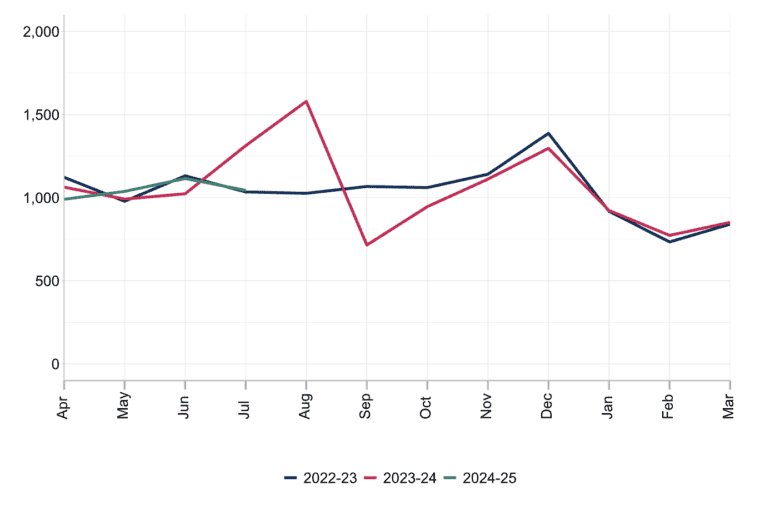

The timing of last year’s announcement awarded trade groups the perfect opportunity to falsely claim duty receipts had fallen. The planned inflationary increase was announced in March 2023 by then-Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, but the new rates only took effect from August 2023, giving producers almost 5 months to clear (and pay duty on) more product than usual, understandably cashing in on the lower rates. This is sometimes referred to as ‘forestalling’. The effect of this is clear when looking at what HMRC received in duty receipts each month last year – July and August saw much higher receipts than usual, whereas in September and October receipts were lower:

Total Alcohol Duty receipts by month, covering April to July of the 2024 to 2025 financial year and all months of the previous 2 years, in £ million

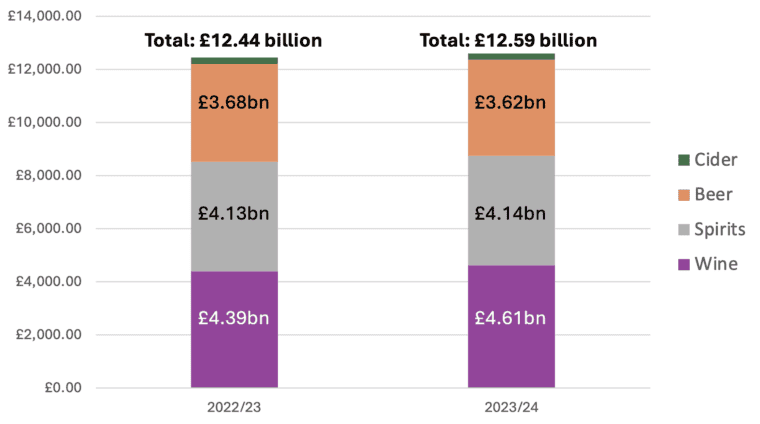

Trade groups have jumped at the opportunity, and used this data to selectively compare periods where receipts were lower than usual, in order to claim that the increase in rates led to reduced Treasury revenue. For instance, the SWA compared from August 2023 onwards, ignoring the elevated receipts in July. The WSTA compared from September, ignoring both the July and August elevated receipts. Despite numerous media outlets reporting these claims, they are easily disproved. When looking across the whole of 2023/24, duty receipts were slightly higher than in the previous year. In fact, the WSTA should instead be celebrating that last year’s wine duty receipts were £220 million higher than the previous year:

Alcohol Duty receipts by product type, 2022/23 and 2023/24, in £ million

Ironically, forestalling really does reduce revenue the Treasury would otherwise collect, but not for the reasons trade groups imply. That is because – as already mentioned – producers pay duty on more product than they otherwise would have done, but at a lower rate. If the rates had gone up but producers hadn’t forestalled, the Treasury would collect more revenue. There is an easy way round this: there should only be a few days between the announcement of new rates and those rates coming into force. Between 2008 and 2012, no more than five days advanced warning was given.

The economic theory behind the claim

Yet of course this is not the argument that trade associations are making for why revenue supposedly falls with duty increases. In fact, they tend to avoid explaining their claim, perhaps because of the economically illiterate theory behind it. As Dr Aveek Bhattacharya has explained far better than I will, the argument rests on the Laffer Curve theory. This simplistic notion is that at 0% tax, government revenue will be zero, and at 100% tax, government revenue will be zero (due to there being no point working or producing anything) – and therefore the appropriate tax rate is somewhere in the middle. This is obvious to the point of meaningless, yet as Dr Bhattacharya states, it has “appeal for the free market right” as it holds out “the possibility that the government could cut tax rates and yet take in more money”. Essentially, proponents of the theory argue that cutting taxes could increase revenue by spurring economic activity.

Ultimately what these trade groups are arguing is that cutting alcohol duty in real-terms will lead to more people buying alcohol and therefore more duty revenue from sales. However, for this to occur drinkers would have to be far more price sensitive than is conceivable. As Dr Bhattacharya wrote about a 2% tax cut a few years ago:

For the 2% cut in duty to have increased Treasury receipts, it would have to cause consumption volume to increase by over 2% to compensate. A 2% cut in duty is likely to be reflected in price cuts of significantly less than 2%, since duty only accounts for a fraction of total selling costs, and may not be fully passed through. As a result, breakeven would imply price elasticity significantly lower than -1. A recent OECD review found that the best evidence suggests that price elasticities are typically closer to -0.5, so British whisky consumers would have to be far more price sensitive than is usually seen in the academic literature. Again, the evidence simply does not support the claims made in favour of cutting alcohol duty.

Narrow-minded economics

What all of this ignores is the wider implications of alcohol duty policy, for instance its effect on the productivity of the UK workforce.

Duty increases could be – and have in the past been – a powerful way of reducing alcohol consumption and harm across the country. Therefore, increasing duty rates could reduce consumption, sales, and duty receipts. Yet alcohol is no ordinary commodity, it has a far wider impact than many other products. If drinking were to fall and the health harms with it, the economic productivity of the UK would increase, with fewer people going to work hungover, fewer people off work sick from alcohol, and fewer people of working age dying from alcohol. Few other products have such a negative effect on economic productivity: in 2018 – before deaths from alcohol significantly increased during the pandemic – Public Health England estimated that almost 180,000 working years were lost due to alcohol in England, amounting to 18% of the total working years lost; a significant impact on the UK’s economic labour supply.

Government policy in recent years has been far too siloed, with short-term Treasury decisions having a wide impact on the health of the UK and government revenue. There is hope that Labour’s ‘mission boards’ – and their longer term and cross-governmental focus – will herald a more sensible and thought-out approach.

Alcohol duty should cover the cost of harm

So beyond a government policy of increasing alcohol duty only a few days after announcing changes to it, what could the new government do to create a more sensible, long-term solution to alcohol duty?

IAS recommends that alcohol duty revenue should cover the external cost of alcohol harm. This position is supported by the Social Market Foundation (SMF), the International Monetary Fund, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies. IAS recently calculated that the cost of harm was at least £27.4 billion in 2021/22 in England alone. Duty receipts for the whole of the UK last year were less than half of that, at £12.6 billion. However, the current methodology on the cost of harm is based on a series of assumptions, and as Kat Petrilli has stated: “highlights the need for a revised methodology that includes more robust research and estimates”. The government is best placed to calculate, or commission the calculation of, the external cost of alcohol harm. As the SMF has called for, the government should then set duty at a rate that covers this cost. Every 5-10 years the cost of harm could be recalculated, and duty rates amended to cover the new cost of harm. Not only would duty then cover the economic externalities alcohol causes, but this mechanism would have a secondary effect of incentivising alcohol producers to genuinely reduce the harm their products cause, in order to reduce their tax burden.

Trade group lobbying should also be far more critiqued than it currently is. The objective of trade associations’ ‘forestalling’ tactic is that decisions and public policy are made on this misinformation. Highly successful lobbying by such groups has led to successive duty cuts, which have contributed to the rise in deaths from alcohol in recent years. Labour can avoid this by bringing in a rational and public health-focused approach to alcohol duty, as we have for tobacco.

Written by Jem Roberts, Senior External Affairs Manager, Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.