View this report

Introduction

This briefing was based on a roundtable meeting hosted by the Institute of Alcohol Studies on 29th June 2023. At the roundtable, Dr Elle Wadsworth presented research on alcohol and cannabis co-use in Canada and the United States immediately before and one year after legalisation of non-medical cannabis in Canada in 2018, and Dr Sadie Boniface facilitated an informal discussion on research gaps and priorities in this area. Attendees included academics and civil society organisations.

Background

Cannabis use is increasingly liberalised across the world. At the time of writing, non-medical cannabis is legalised in 23 US states and the District of Columbia, Canada, Uruguay, among others. In Europe, Luxembourg and Malta have moved to legalisation of non-medical cannabis use. More recently, Germany’s government has published a draft bill to legalise the use of cannabis for personal use, which could trigger other countries in Europe to pursue cannabis legalisation (Sabaghi, 2023).

People who use cannabis are likely to use alcohol too but measuring and understanding cannabis and alcohol co-use is complex. Previous literature has focused on understanding whether cannabis and alcohol are ‘substitute’ or ‘complementary’ substances for each other. In addition, cannabis and alcohol co-use can also be defined as simultaneous co-use or use of both substances but not necessarily at the same time, for example, over the course of a typical month.

Developing an understanding of what has happened in jurisdictions where non-medical cannabis has been legalised, such as Canada and the United States, can provide lessons on the impacts and outcomes of legalisation for alcohol use and harm, and provide lessons for alcohol policy.

Case study: Co-use of cannabis and alcohol before and after Canada legalised non- medical cannabis in 2018 (Hobin et al., 2023)

Cannabis and alcohol are two of the most commonly used psychoactive substances in Canada and the United States, with similar patterns observed in the UK. An earlier study reported an increase in co-use of alcohol and cannabis in US states where non-medical cannabis was legal compared to US states where it was not legalised (Kim et al., 2021). Another study reported a small increase in co-use after the legal cannabis market opened in Washington State (Subbaraman & Kerr, 2020).

In this study, co-use was defined as monthly or more frequent use of both cannabis and alcohol. The study used repeated cross-sectional survey data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (ICPS) to examine whether non-medical cannabis legalisation in Canada was associated with changes in regular co-use of cannabis and alcohol relative to US states that had and had not legalised non-medical cannabis. The ICPS survey provides detailed population-based data using policy-specific measures across multiple countries.

The results showed an increased in cannabis use and co-use of alcohol and cannabis between 2018 and 2019 in Canada and the US. There was no evidence to suggest differences in patterns of co-use in this period between Canada and comparator US states where cannabis was legal or illegal. The observed increases in co-use between 2018 and 2019 were largely due to increases in cannabis use across the population, including in people who used alcohol.

Changes in Public Opinion, Patterns of Use, and Cannabis and Alcohol Co-Administration

In the US, with changes towards the liberalisation of cannabis policies, studies suggest people are becoming more supportive of non-medical cannabis legalisation (Chiu et al., 2021). There has been a decline in perceived risk of cannabis use, and a reduction in the price of products, accompanied by an increase in the potency of products available (Chiu et al., 2021). In Canada, the objective of the of legalisation were “to prevent young persons from accessing cannabis, to protect public health and public safety by establishing strict product safety and product quality requirements and to deter criminal activity by imposing serious criminal penalties for those operating outside the legal framework” (Cannabis Act, 2018). Following this, cannabis legalisation has been associated with a reduction in cannabis-related arrests, as well as increases in prevalence of cannabis use in young adults but not in high school students (Hall et al., 2023). Legalisation has also resulted in increased access to a variety of higher potency products at lower prices (Hall et al., 2023). In the US non-medical cannabis was first legalised in Colorado and Washington in 2012, and in Canada non-medical cannabis was legalised in 2018. However, it is still too soon to fully understand the effects on public health of different regulatory approaches.

The impact on alcohol use and harm should form part of any evaluation following changes to the legal status of cannabis. This could include ensuring surveys, e-health records, and analytical capacity are sufficient to monitor emerging trends, as well as measuring the impact on public health and inequalities.

Psychopharmacological studies suggest simultaneous consumption of alcohol and cannabis might result in increased levels of Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in the blood, the main psychoactive component in cannabis (Hartman et al., 2015). Simultaneous consumption has also been associated with negative additive effects, such as poorer driving performances when using both substances (Downey et al., 2013).

The public health impact of potential changes in simultaneous co-use is an unexplored area of research by population-based studies, and further research could add to conversations around policy considerations for alcohol and cannabis use.

Impact of Cannabis Legalisation on Drug and Alcohol Services

Most treatment services in the UK are combined alcohol and drug services. Cannabis regulation could potentially have an impact on treatment services by increasing access to and use of cannabis and, as a result, increasing the prevalence of cannabis use disorder (CUD). CUD is a clinical diagnosis broadly defined as the continued use of cannabis despite clinically significant impairment (American Psychiatry Association, 2013). A higher prevalence of CUD and more people seeking treatment could put extra pressure on treatment providers, in an already stretched system.

The evidence so far from other countries does not seem to suggest an increase in CUD following legalisation. For example, US states that have legalised non-medical cannabis has not seen a significant rise in people seeking treatment for CUD following legalisation of cannabis (Aletraris et al., 2023; Mennis et al., 2023). However, it is worth noting that changes in rates of CUD may not come immediately after legalisation. In the UK where cannabis is illegal, rates of cannabis use has remained fairly stable while rates of treatment seeking for cannabis use problems have increased significantly over the last decade (Manthey, 2019). This shows that the prevalence of CUD and treatment seeking behaviour is impacted by a wider range of factors, such as the strength of the cannabis (Freeman, 2019), prompting proposals to cap THC content in cannabis or tax cannabis products based on THC content (Hall et al., 2023).

Further research is needed to understand the impact that different cannabis use patterns and legalisation models can have on health outcomes and substance use treatment systems. These are important considerations when informing public health policies seeking to regulate cannabis products.

Public Health and Social Justice Considerations in Different Cannabis Legalisation Models

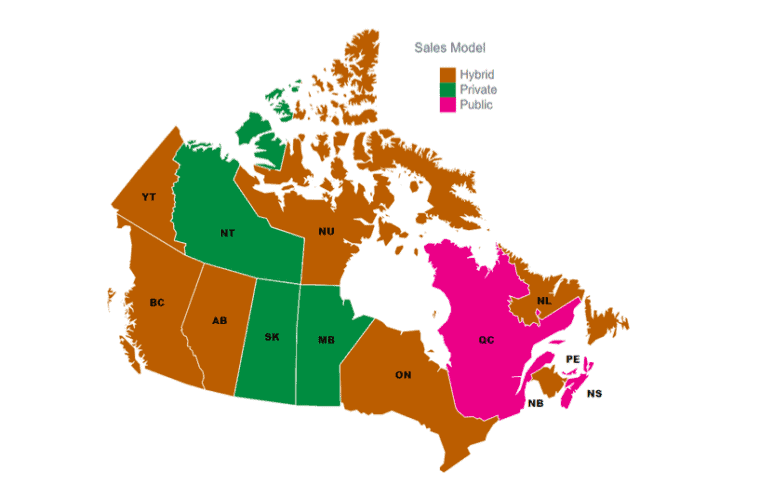

In Canada, production, distribution, sales, and possession of cannabis is enacted at the Federal level by the Cannabis Act. Regulations to do with industry-wide rules and requirements for producers and manufactures are set at the federal level, but provinces and territories oversee the distribution and sale of cannabis products. This means that how and where cannabis can be sold, as well as whether outlets are public or private, is different across provinces and territories (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2023; Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020b), see Figure 1. In the US, cannabis remains illegal at the federal level. Cultivation, possession, and sale of cannabis is independently regulated at the state level, resulting in considerably different regulations across jurisdictions (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020a).

Figure 1. Provincial and Territorial Cannabis Regulations, Canada, from “Interactive Map of Provincial and Territorial Cannabis Regulations” (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2023)

Note that since this figure was created Alberta has changed its sales model from hybrid to fully private.

Whilst it is possible to compare the principles and initial impacts of these different models, long term studies are still needed to understand detailed consequences, such as the impacts of different licensing models. Further consideration on the overlaps between cannabis and alcohol policy, as well as lessons that could be shared from different legalisation models is needed. Some aspects of cannabis regulatory models across Canada and the US are presented in Table 1, together with alcohol regulations for comparison.

Table 1. Cannabis and alcohol regulatory models in Canada and US

Availability

Cannabis

In Canada, provincial and territorial governments control retail. Cannabis can be sold online and in physical retail stores. There are three types of retail models at both levels across Canada: public, private and hybrid (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2023). Government-only models may imply a more precautionary approach by reducing incentive to maximise private profit. Where private companies are permitted, they are required to follow strict licensing requirements. Regulation can also determine outlet density and retail location, to avoid encouraging use while also ensuring availability of retail stores and reduction of the illegal market (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020b). Similarly, in the US, the number of stores and locations is regulated through licenses at the state level (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020a).

Alcohol

In Canada, provincial and territorial governments control the sales and distribution of alcohol. Each province and territory have a separate agency responsible for regulating the sales of alcoholic drinks. Most provinces and territories have a combination of private and government outlets (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, 2018). Similarly, in the US, alcohol sales and distribution are regulated at the state level. This means that there are significant differences across states and local jurisdictions. The retailing or wholesaling of some or all alcoholic beverages in 17 states is controlled by a state monopoly (National Alcohol Beverage Control Association, n.d.).

Marketing

Cannabis

In Canada, advertisement and promotion is regulated at the federal level. Appealing to young people by promoting cannabis use with ‘glamour, recreation, excitement, vitality, risk, daring’ is prohibited but brand elements are allowed in marketing (Government of Canada, 2019). The Cannabis Act also prohibits cannabis products from being linked with alcohol, tobacco, or non-cannabis vaping products. Further restrictions, such as prohibitions on providing cannabis samples, may be applied at the provincial and territorial level (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020b).

Canada has also implemented regulations requiring plain packaging and labelling for all cannabis products with restrictions on logos, colours, and branding. This includes allowing only a single uniform colour for the packaging as well as requiring health warning messages (Government of Canada, 2022b). In the US, most states have also introduced regulations to prevent cannabis marketing targeting children. Other states have also imposed controls on packaging designs and requirements for business to measure the impact of their advertisement in order to ensure it is compliant (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020a).

Alcohol

In Canada, the Canadian Radio-Television Telecommunications Commission regulates marketing and promotion of alcohol on television and radio, restricting advertising to youth at the federal level. Additional regulations are placed at the province and territory level (Wettlaufer et al., 2017). In the US, on the federal level many of the regulations for alcohol advertisement are dependent on self-regulation. However, states may have specific rules. The majority of regulations focuses on underage drinking and preventing appealing to audiences under the age of 21 years (American Addiction Centers, 2022).

Taxation

Cannabis

In Canada, cannabis is taxed both at the federal and provincial level according to product type. The use of tax revenue can vary across provinces and territories. In Quebec, which has a public sales model, revenue is remitted to the Quebec government for investment primarily into cannabis prevention and research (Société québécoise du cannabis, n.d.). In the US, cannabis is taxed differently depending on the state. States use percentage-of-price taxes, weight-based taxes, or potency-based-taxes. Municipalities may also impose local taxes in addition to the general state tax. In theory, tax revenue acquired by states can be spent on anything. Most states dedicate at least some of the revenue to specific spending programs. Some states such as Illinois and Oregon allocate part of the state taxes to community services that aim to address substance use and mental health concerns. (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020a).

Alcohol

In Canada, the Federal government establishes federal tax rates on alcoholic beverages. The tax rate depends on the type of alcohol and absolute ethyl alcohol by volume. All provinces and territories have implemented retail sales taxes on the purchase of alcohol (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, n.d.). In the US, there are federal-specific taxes for different types of alcoholic beverages, applied based on a fixed amount per volume of alcohol. In addition, three types of taxes may be applied to alcoholic drinks sold in states: specific excise taxes, ad valorem taxes, and general sales taxes (Blanchette et al., 2019).

Another outcome highlighted when considering cannabis legalisation is how to promote social justice and address the harms of prohibition. Cannabis-related arrests accounted for over half of drug related arrests between 2000 and 2010 in the US (American Civil Liberties Union, n.d.). Similarly, in England and Wales, ‘possession of cannabis’ has consistently been the most commonly recorded drug offence (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2022b), making up about two thirds of all drug offences recorded 2021 (Allen & Tunnicliffe, 2021). Under prohibition, marginalised groups, particularly Black and minority ethnic communities are disproportionally impacted by the negative impacts of law enforcement (Cohen, 2019; Shiner et al., 2018) and social justice arguments have been part of narratives around decriminalisation and legalisation. Legalisation models provide an opportunity to reduce harms and possibly enable reparations to these communities, through addressing these injustices. For example, by allowing individuals to clear cannabis offences from their records, thus, ensuring they do not continue to experience the health and economic implications associated with having a drug offence (Kilmer & Neel, 2020). Another outcome receiving increasing attention is how cannabis legalisation can promote social equity (Kilmer & Neel, 2020). This can include implementing programmes that provide employment and economic opportunities to people and communities disproportionally impacted by the war on drugs (Owusu-Bempah, 2021), and providing the chance to benefit from spending following increased revenue from taxation (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020). As with public health effects, different cannabis legalisation models are likely to have various social effects (Kilmer & Neel, 2020).

Commercial Determinants of Health and Corporate Capture

The emergence of the Canadian cannabis market resulted in huge investments for what was speculated to be an extremely profitable new commodity. While stock prices dropped dramatically in the second half of 2019 when the market picture became clearer and the cannabis industry speculator ‘bubble’ burst (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020b), several multinational cannabis producers have been established in Canada (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2022a). These companies are in a prime position in the Canadian cannabis market and international markets.

Micro-licences are a key feature introduced in Canada’s licencing framework with the aim of supporting participation of small-scale growers and processers in the legal supply chain. Micro-licences have a smaller maximum limit of growing surface and possession of cannabis with lower fees and security requirements than a standard licence (Government of Canada, 2022a). In 2022, 38% of all federal licence holders were micro-licence holders but by the end of 2021, 43% of dried cannabis production came from 10 standard licence holders and 66% of all revenues was accounted for by 10 parent companies (Government of Canada, 2022a).

Larger producers, such as Canopy Growth, are represented on the board of the Cannabis Council of Canada, Canada’s national organisation of federally licenced cannabis producers aiming to promote industry standards. The Cannabis Council of Canada has previously argued against increased regulation, including bans on edibles and limits to THC levels. These dynamics of corporate capture are a significant concern, which has been amplified by significant investments from alcohol and tobacco corporations in the Canadian cannabis sector (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2020b).

Canadian companies have also made a strong base in international expansion. So far this has mostly been on the medical market but diversifying from medical to non-medical cannabis is relatively simple because they are the same products, even if they might be regulated and used differently (e.g., smoked versus vaporised) (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2022a). For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean where more than a dozen countries have introduced some form of medical cannabis regulation, corporations based in Canada and other wealthy countries such as the US and the UK are setting up operations in the region (dos Reis Pereira, 2022). This provides commercial advantages to these corporations such as lower costs to manufacture their products and expansion of their consumer market, while diminishing potential social gain in the region by reinforcing inequalities and promoting dynamics of exploitation between the global North and South (dos Reis Pereira, 2022).

The legal cannabis market has also led to opportunities for alcohol and tobacco companies to diversify their products, raising concern due to the corporate power and influence of these companies and history of opposing public health policies. An example of this was the partnership aiming to create drinkable cannabis products between two of the largest alcohol companies in the world, AB InBev and Molson Coors, and Canadian cannabis companies Tilray (Lindenberger, 2023) and HEXO respectively (MJBizDaily, 2022). In addition, in 2020 Constellation Brands, the third largest market share holder of all beer companies, had ownership of 38.6% of Canopy Growth’s shares (MJBizDaily, 2020).

Further analysis is needed to understand how cannabis liberalisation might provide an opportunity for product innovations in the alcohol industry, and how these should be regulated when considering alcohol harm.

Conclusion

Alcohol regulation in the UK has significant issues, particularly around marketing. Marketing of alcohol is a mix of co-regulation and self-regulation, with commercial stakeholders involved in how products are promoted. If the UK moves towards the legalisation of cannabis, there is a lot it can learn from alcohol policy regarding what to avoid to ensure that the power of commercial entities is sufficiently limited through regulation of price, availability and marketing.

Monitoring research findings from jurisdictions that have regulated cannabis can provide lessons on the impacts and outcomes of legalisation for alcohol use and harm, and provide lessons for alcohol policy too. Monitoring the effects of cannabis regulation should also seek to assess the extent to which social justice improvements may have public health benefits. Further work is needed that seeks to develop opportunities to apply learning from alcohol to future regulatory models for cannabis and vice-versa.

Aletraris, L., Graves, B. D., & Ndung’u, J. J. (2023). Assessing the Impact of Recreational Cannabis Legalization on Cannabis Use Disorder and Admissions to Treatment in the United States. Current Addiction Reports, 10(2), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429- 023-00470-x

Allen, G., & Tunnicliffe, R. (2021). Drug Crime: Statistics for England and Wales [House of Commons Library]. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP- 9039/CBP-9039.pdf

American Addiction Centers. (2022). Rules & Regulations About Marketing Alcohol. https://alcohol.org/laws/marketing-to-the-public/

American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.). Marijuana Arrests By The Numbers. https://www.aclu.org/gallery/marijuana-arrests-numbers

American Psychiatry Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Cannabis Act, SC 2018, C 16 (2018).

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2023). Cannabis Policy map. https://www.ccsa.ca/policy-and-regulations-cannabis

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. (2018). Provincial/Territorial Alcohol Policy Pack. https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/provincial-territorial- alcohol-policy-pack-en.pdf

Chiu, V., Leung, J., Hall, W., Stjepanović, D., & Degenhardt, L. (2021). Public health impacts to date of the legalisation of medical and recreational cannabis use in the USA. Neuropharmacology, 193, 108610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108610

Cohen, D. (2019). The Cannabis Debate: Ethnic minorities twice as likely to be arrested for possession. https://www.standard.co.uk/evening-standard/news/uk/the-cannabis-debate- ethnic-minorities-twice-as-likely-to-be-arrested-for-possession-a4182331.html

dos Reis Pereira, P. J. (2022). Corporate Capture of the Latin American Medical Cannabis Market. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/corporate-capture-of-the-latin-american-medical- cannabis-market

Downey, L. A., King, R., Papafotiou, K., Swann, P., Ogden, E., Boorman, M., & Stough, C. (2013). The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated driving: Influences of dose and experience. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 50, 879–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.07.016

Freeman, T. (2019). Cannabis Potency and Treatment Admissions. Society for the Study of Addiction. https://www.addiction-ssa.org/knowledge-hub/cannabis-potency-and- treatment-admissions/

Government of Canada. (2022a). Taking stock of progress: Cannabis legalization and regulation in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/programs/engaging- cannabis-legalization-regulation-canada-taking-stock-progress/document.html

Government of Canada. (2019). Policy statement on Cannabis Act prohibitions referring to appeal to young persons. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/cannabis- regulations-licensed-producers/prohibitions-referring-appeal-young-persons.html

Government of Canada. (2022b). Packaging and labelling guide for cannabis products. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/cannabis-regulations-licensed- producers/packaging-labelling-guide-cannabis-products/guide.html#a6

Hall, W., Stjepanović, D., Dawson, D., & Leung, J. (2023). The implementation and public health impacts of cannabis legalization in Canada: A systematic review. Addiction, add.16274. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16274

Hartman, R. L., Brown, T. L., Milavetz, G., Spurgin, A., Gorelick, D. A., Gaffney, G., & Huestis, M. A. (2015). Controlled Cannabis Vaporizer Administration: Blood and Plasma Cannabinoids with and without Alcohol. Clinical Chemistry, 61(6), 850–869. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.238287

Hobin, E., Weerasinghe, A., Boniface, S., Englund, A., Wadsworth, E., & Hammond, D. (2023). Co-use of cannabis and alcohol before and after Canada legalized nonmedical cannabis: A repeat cross-sectional study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 37(5), 462– 471. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231161583

Kilmer, B., & Neel, E. K. (2020). Being thoughtful about cannabis legalization and social equity. World Psychiatry, 19(2), 194–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20741

Kim, J. H., Weinberger, A. H., Zhu, J., Barrington-Trimis, J., Wyka, K., & Goodwin, R. D. (2021). Impact of state-level cannabis legalization on poly use of alcohol and cannabis in the United States, 2004–2017. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108364

Lindenberger, H. (2023). Tilray Brands Deal With Anheuser-Busch InBev Sets Them Firmly On The National Stage. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hudsonlindenberger/2023/08/08/tilray-brands-deal-with- anheuser-busch-inbev-sets-them-firmly-on-the-national-stage/

Manthey, J. (2019). Cannabis use in Europe: Current trends and public health concerns. International Journal of Drug Policy, 68, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.006

Mennis, J., Stahler, G. J., & Mason, M. J. (2023). Cannabis Legalization and the Decline of Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) Treatment Utilization in the US. Current Addiction Reports, 10(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00461-4

MJBizDaily. (2020). Constellation ups stake in marijuana producer Canopy Growth to 38%. https://mjbizdaily.com/constellation-ups-stake-in-canopy-growth-to-38/

MJBizDaily. (2022). Molson Coors exiting CBD drink joint venture in US with Hexo. https://mjbizdaily.com/molson-coors-exiting-american-cbd-drink-joint-venture-with-hexo/

National Alcohol Beverage Control Association. (n.d.). Alcohol Regulation 101. https://www.nabca.org/structure-us-alcohol-regulation

Owusu-Bempah, A. (2021). Where Is the Fairness in Canadian Cannabis Legalization? Lessons to be Learned from the American Experience. Journal of Canadian Studies, 55(2), 395–418. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs-2020-0042

Sabaghi, D. (2023). Germany Unveils Draft Bill To Legalize Cannabis. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dariosabaghi/2023/07/10/germany-unveils-draft-bill-to- legalize-cannabis/

Shiner, M., Carre, Z., Delsol, R., & Eastwood, N. (2018). The Colour of Injustice: ‘Race’, drugs and law enforcement in England and Wales. https://www.release.org.uk/publications/ColourOfInjustice

Société québécoise du cannabis. (n.d.). Strategic Plan 2021-2023 for responsible consumption. (link to download)

Subbaraman, M. S., & Kerr, W. C. (2020). Subgroup trends in alcohol and cannabis co- use and related harms during the rollout of recreational cannabis legalization in Washington state. International Journal of Drug Policy, 75, 102508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.003

Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2020a). Altered States: Cannabis Regulation in the US. https://transformdrugs.org/publications/altered-states-cannabis-regulation-in-the-us

Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2020b). Capturing the Market: Cannabis regulation in Canada. https://transformdrugs.org/publications/capturing-the-market

Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2022a). How to Regulate Cannabis A Practical Guide. https://transformdrugs.org/publications/how-to-regulate-cannabis-3rd-ed

Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2022b). The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971: Counting the Costs. https://transformdrugs.org/publications/the-misuse-of-drugs-act-counting-the-costs

Wettlaufer, A., Cukier, S. N., & Giesbrecht, N. (2017). Comparing Alcohol Marketing and Alcohol https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1281308

Warning Message Policies Across Canada. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(10), 1364–1374. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1281308

View this report