Australia’s Northern Territory has removed its Minimum Unit Price (MUP) for alcohol as of the first of March. The removal of the MUP was an election promise of the incoming Country Liberal Party (CLP), who had opposed the introduction of the policy in 2018 by the Territory Labor Party. Party politics no doubt played a major role in the choice to remove the policy. Alcohol policy is a contentious issue in the Northern Territory and the major parties have a long-established history of removing reforms introduced by the other. From the time the intention to repeal was announced through to the final debates, the CLP used a series of varied arguments to justify their decision.

What arguments were used to justify the repeal?

The CLP’s main argument was that the MUP simply ‘did not work’, predominantly leaning on the increase in raw numbers of alcohol-related assaults from 2018 until now. This is in line with their crime-focused framing of alcohol, a context in which the stronger evidence of reduced negative health outcomes carried little weight. Politicians attributed the rise in assaults to the policy causing drinkers to switch from cheap wine, the target of the policy, to spirits, which have been framed as a more dangerous form of alcohol. By removing the policy, the CLP argued that drinkers would switch back to the ‘safer’ cask wine, and thus a drop in alcohol-related assaults should follow. This reasoning relies on two key points, that drinkers switched from wine to spirits, and that the rise in alcohol-related assaults can be attributed to the introduction of the MUP. Neither point is supported by available evidence.

The argument against the switch to spirits

Politicians referred to a three-year evaluation of the MUP to affirm this claim that drinkers switched to spirits. It is true that trends show an increase in spirits consumption in the Northern Territory, however this occurred in the context of a nation-wide increase in spirits consumption at this time, across many jurisdictions without an MUP. The report acknowledges this, stating that that the rise in spirits consumption did not coincide with the introduction of the MUP in the data they had available and that the MUP was very unlikely the cause of increased spirits consumption. This is supported by the national trend which suggests confounding. To date no study has been able to demonstrate a switch to spirits. The narrative that the MUP caused cask wine drinkers to switch to spirits has long been peddled by the alcohol industry, which they repeated in interviews undertaken as part of the three-year evaluation of the MUP. Regardless, this switch was stated as ‘fact’ by members of the CLP in the lead up to the removal of the policy. Financially, the switch from cheap wine to spirits does not add up, wine could be purchased for as little as AU$0.60 per standard drink (10grams of alcohol) prior to the MUP implementation, while spirits averaged over AU$2.50 per standard drink. There were many beer and wine products available at AU$1.30 after the introduction of the MUP, which would make them a more affordable and likely substitution than spirits.

The argument against the MUP causing a rise in assaults

Rates of alcohol-related assaults have risen in the NT, but to attribute the trend to the MUP would be misleading. Robust time-series analyses demonstrate a significant immediate drop in alcohol-related assaults in the major region of the NT where such a change could only be attributed to the MUP. There are a variety of highly plausible reasons for the increasing assaults. MUP acts on the lever of affordability, and thus, changes in the economy such as inflation are highly influential, hence the NT’s legislation to index the MUP (which was not implemented by the former Labor government). This means that over the course of the policy, inflation likely weakened the MUP. Beyond this, the MUP was likely set too low in the NT, only having roughly half of the coverage of its Scottish counterpart. The broader alcohol policy context is also highly relevant, with other key alcohol policies aimed at reducing alcohol-related harm being dismantled and reimplemented during this period. Finally, there was a worldwide pandemic. Like any alcohol policy, the design and maintenance of the policy, and its interaction with other policies that comprehensively address the drivers of alcohol harm, is essential.

Moving forward

The MUP did in fact achieve its aim of reducing cheap wine which it continues to achieve to this day (see below figure).

The majority of evidence indicates that it also improved health outcomes and decreased violence within the Northern Territory. This was done with zero implementation costs, and with negligible financial impact on moderate alcohol consumers. However, the policies impact likely eroded overtime due to the lack of proper maintenance by the prior government. The narrative pushed by the CLP to justify their removal of the MUP is not based on evidence and given the evidence available, the repeal can largely be attributed to the politicisation of alcohol policy. MUP remains a highly effective and cost-effective measure to reduce alcohol harm, which policymakers can design to reduce harms targeting drinkers and beverages of concern. The narratives pushed in the NT will likely be pushed in other jurisdictions. Action must be taken to prevent these baseless claims from undermining effective alcohol policy globally.

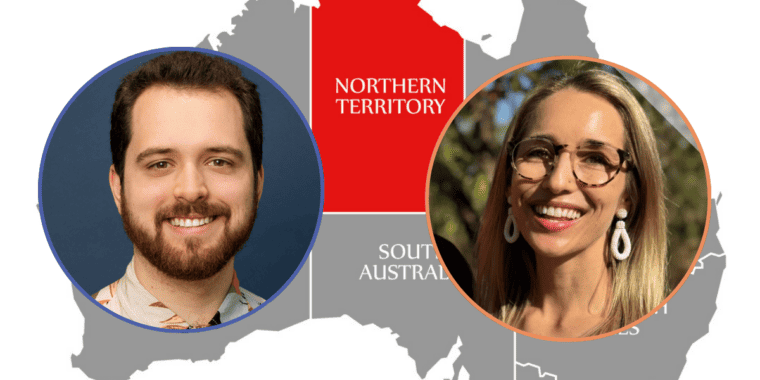

Written by Dr Nic Taylor, National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University and Dr Cassandra Wright, Alcohol and other Drugs team, Menzies School of Health Research.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.