Alcohol policies are important for reducing the negative effects of alcohol. The World Health Organisation recommends that countries take steps to control how alcohol is priced, advertised and sold. For example:

- Pricing: Governments can increase taxes on alcohol or set a minimum price, so it’s less affordable to buy alcohol.

- Advertising: Rules can limit how often and where alcohol ads appear, as well as what messages they promote.

- Availability: Restrictions might reduce the number of shops that sell alcohol or shorten the hours during which it’s available.

Creating and enforcing these policies can be challenging because public opinion plays an important role. If people don’t support the policies, they may fail to work. However, if governments focus only on what’s popular, they might overlook scientific evidence about what is most effective for improving health. Striking a balance between public support and health research is key to creating successful alcohol policies.

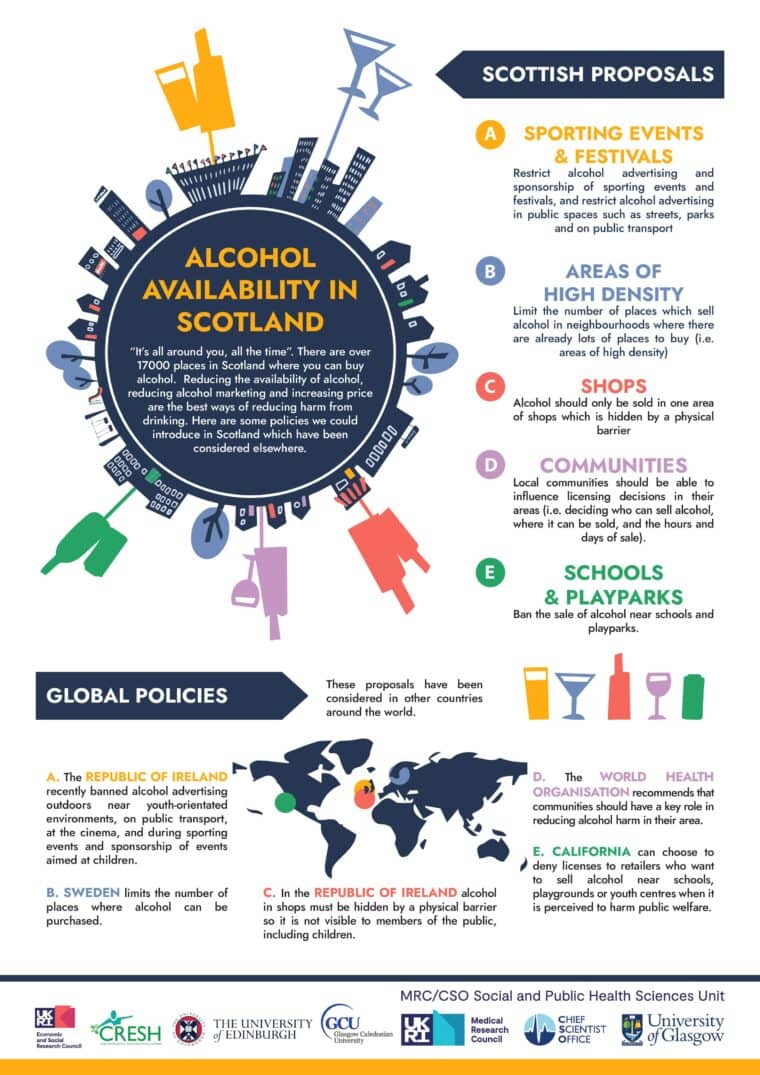

In our recent research, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, we explored both public and professional stakeholders’ opinions on several policy suggestions to reduce alcohol use and harms. We spoke to 45 people living in different neighbourhoods across Scotland and 14 professionals from third sector, policy, public health and alcohol licensing. We presented them with a list of policy suggestions (Figure 1) and discussed their views on acceptability, feasibility and likely success. Below we report the findings by policy suggestion.

Figure 1. Policy suggestions used in the study.

Restrict alcohol advertising and sponsorship of sporting events and festivals, and restrict alcohol advertising in public spaces such as streets, parks and on public transport.

All professional stakeholders agreed that regulating alcohol advertising is a clear policy priority. Some of the public stakeholders questioned why alcohol is advertised in Scotland while other unhealthy products, such as cigarettes, are not: “They would not let cigarette companies on the football t-shirts, so I would not let alcohol on it either”. Related to sponsorship of events, the public discussed the role alcohol plays in Scottish culture, especially in relation to sport and music, with some suggesting that drinking is part of the experience at sport and music events.

Ban the sale of alcohol near schools and playparks.

Although all of our participants were supportive of this suggestion, they believed that children are exposed to alcohol in their wider environment. For example, professional stakeholders suggested that “children don’t actually stay within local areas” and a child may take a bus “seven kilometres away, and then passes so many adverts on the bus”. Public stakeholders added that children get “their attitudes towards alcohol from home”, so banning the sale of alcohol near schools is unlikely to reduce their exposure to alcohol.

Limit the number of places which sell alcohol in neighbourhoods where there are already lots of places to buy it.

Professional stakeholders told us that alcohol availability is a public health issue. Public stakeholders said that there are “too many shops selling alcohol” in Scotland, but did not see this as a public health issue. They did not believe that reducing the number of places selling alcohol would reduce drinking among adults. Public stakeholders suggested that “if you’re gonna go for alcohol you’re gonna get alcohol. It doesn’t matter how many places are open … if there’s one store or five stores, I don’t think it’ll make a difference.” There was discussion whether this policy could lead to economic losses for small retailers or discourage supermarkets to open in communities, which would benefit from job creation and fresh produce. Some suggested that alcohol is available online so reducing the number of shops selling alcohol may not reduce drinking.

Alcohol should only be sold in one area of the shop which is hidden by a physical barrier.

Professional stakeholders favoured the physical separation of alcohol from other products as a way to de-normalise alcohol as an everyday product (e.g., “outta sight, outta mind”). Public stakeholders did not believe that selling alcohol behind a physical barrier would reduce drinking among adults: “If you’re of age and drinking, you tend to know what you like to drink, so you’re just gonna ask for it anyway.” There were discussions among the public about the potential of this policy to protect children by reducing their exposure to alcohol products, suggesting “it’s challenging the normality and the fact that alcohol seems to be a core part of what we do”.

What do these findings mean?

This study shows the need for policy makers to take public opinions into account when creating alcohol policies and recognise that these views are shaped by conflicting ideas about alcohol. Members of the public saw policies to reduce alcohol availability as relatively simple attempts to influence a complex social issue. When discussing these policies, they focused on ‘others’, such as heavy and dependent drinkers, while rejecting measures that might affect their own drinking. Public health stakeholders also weighed the benefits of reducing alcohol-related harms against potential downsides, such as limiting personal freedom and financial losses for small businesses. There was agreement that alcohol control policies have the potential to protect children from alcohol exposure and contribute towards cultural change. To gain public support for alcohol control policies, it is important to share scientific evidence about alcohol policies in a way that clearly explains both their benefits and any potential risks. This should consider people’s concerns about how effective policies are, their possible unintended consequences, and the broader role alcohol plays in society. There is a need for research to understand online availability and explore children and young people’s voices in relation to alcohol control policies.

Written by Dr Elena D. Dimova, Substance Use Research Group, Glasgow Caledonian University.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

Acknowledgment: The publication referred to in this blog was authored by Elena D. Dimova1, Niamh K. Shortt2, Matt Smith1, Richard J. Mitchell3, Peter Lekkas2, Jamie R. Pearce2, Tom L. Clemens2,, Carol Emslie1

1 Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK

2 Centre for Research on Environment, Society and Health, School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

3 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute for Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK