Understanding and interpreting patterns in crime has been a long-standing focus for criminologists and policymakers. Where levels rise, identifying this could allow action to be taken to ameliorate this. But what about when levels fall? Interpreting fluctuations in different crime patterns might offer insight into the macro, meso, and micro levers that drive their incidence. These insights could, at least theoretically, be harnessed by policymakers to reduce levels further.

This is why the Institute of Alcohol Studies has published a report examining recent patterns in alcohol-related violence. In England and Wales, official statistics on alcohol-related violence are drawn from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) – an annual nationally representative household survey capturing experiences of victimisation in the last year (for more information, see here).

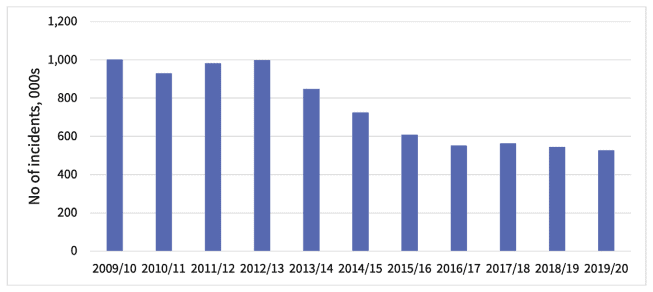

Across the ten years between 2009/10 and 2019/20, overall levels of alcohol-related violence have fallen – from 1,001,000 incidents in 2009/10 to 525,000 in 2019/20 (Office for National Statistics, 2021a). What’s more, while this has happened alongside broader declines in violence as a whole, declines in alcohol-related violence have been steeper. While none of this undermines the seriousness of alcohol-related violence as a policy problem (as there are still more than half a million incidents of this violence each year), exploring this decline could point us towards violence reduction measures that could hasten this further.

The report – Patterns in alcohol-related violence: exploring recent declines in alcohol-related violence in England and Wales – is exploratory, drawing on existing bodies of literature and published crime data to make proposals about what could be behind the decline. Three ideas are judged worthy of further investigation:

Are declines in youth drinking influencing levels of alcohol-related violence?

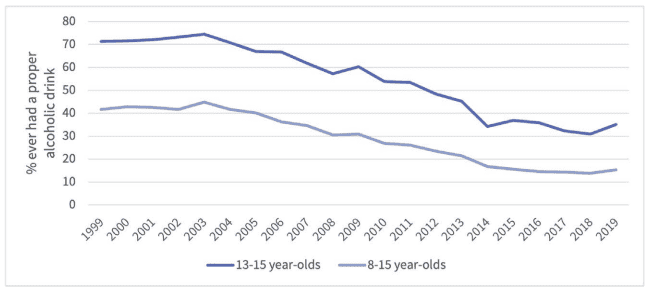

Drawing on sources including the Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Among Young People survey, some have identified that young people today are drinking less than their peers of prior decades. The Institute of Alcohol Studies has explored this phenomenon in its report Youthful Abandon: why are young people drinking less, read more here. Could this explain the reduction in alcohol-related violence seen?

First, the timeline of the declines recorded in youth drinking align to some degree with those of alcohol-related violence – see Figures 1 and 2 below. Second, it is recognised that violence in night-time economy settings generally involves younger age groups. Finally, the declines in drinking seen have been shown to affect heavier young drinkers to the greatest degree – we might theorise those most likely to reach the state of intoxication thought to contribute to violence.

Figure 1: Number of violent incidents reported to the CSEW which were alcohol-related. Office for National Statistics (2021a)

Figure 2: Children (8-15 years old in England) who have ever drunk. NHS Digital (2020)

Are all kinds of alcohol-related violence declining?

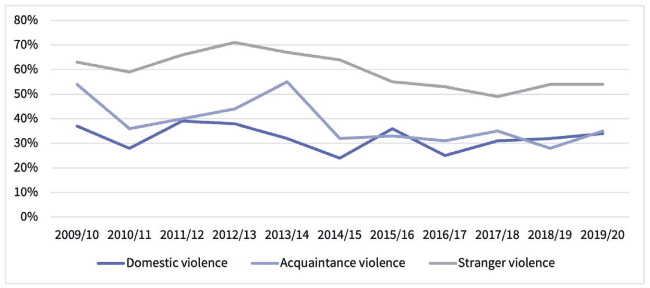

Violence is a broad category, and while any instance of aggression may share some drivers, it is widely accepted that different kinds of violence – e.g., domestic as opposed to stranger violence – may have their own distinct drivers. Therefore, it is essential we examine trends in such alcohol-related violence subtypes.

As Figure 3 shows, the proportion of stranger and acquaintance violence which was recorded as alcohol-related over this period has fallen (from 63% to 54% and 54% to 35% respectively). That same proportion has remained steadier for domestic violence. Given that reported overall levels of stranger and acquaintance violence have also remained higher across this decade (see Office for National Statistics (2021b) for more detail), this suggests declines in alcohol-related stranger and acquaintance violence drive the recorded declines in alcohol-related violence overall to the greatest degree.

Figure 3: Proportion of violent incidents reported to the CSEW which were alcohol-related, by subtype. Office for National Statistics (2021c)

This could lend support to the suggestion on youth drinking already discussed. But it should also give pause to policymakers – behind the declines, there remains a consistent proportion of incidents of domestic violence that are alcohol-related and addressing these should not be discounted as a policy priority.

Is the decline as large as the survey suggests?

The Crime Survey for England and Wales is a renowned data source – however, it is possible that data artefacts like counting errors may affect the trend reported.

One area that warrants investigation is the gap in domestic violence reporting between the in-person and self-completion sections of the CSEW. Incidents of domestic violence are counted in two ways through the CSEW. Respondents are asked to report experiences of violence in a face-to-face interview and in ‘self-completion modules’ without an interviewer, answering questions on a computer. These self-completed reports of violence do not form part of the violence figures discussed in this report, and respondents are not asked about the alcohol-related nature of any incident here.

However, in 2019/20, only 10.3% of those who reported experiences of domestic violence (physical force) victimisation through this self-completion module also reported this in their face-to-face interview. This means the domestic violence counts which form part of the alcohol-related violence figures discussed in this report “are an under-estimation of the true extent of this type of violence”.

These theories explored in this report offer promise towards explaining reported declines. Researchers and policymakers should take investigation forward to see if any policy lever can be pulled to enhance the influence of these further and bring violence levels down once more.

Importantly, though, the declines described in this report should not encourage complacency. As more than half a million instances of alcohol-related violence take place each year, evidenced action is needed – including on price, consumption, and marketing.

Written by Lucy Bryant, Research and Policy Officer, Institute of Alcohol Studies, and Lecturer in Criminology, Open University.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

References:

- Office for National Statistics. (2021a). The nature of violent crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2020; Table 9a: Proportion of violent incidents where the victim believed the offender(s) to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. London: Office for National Statistics.

- Office for National Statistics. (2021b). Crime in England and Wales, year ending March 2020 – Appendix tables; Table A6: Trends in the offender relationship of CSEW violence from year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2020, with percentage change and statistical significance of change. London: Office for National Statistics.