In January, Canada released new drinking advice called Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health. As a member of the scientific committee tasked with authoring this new guidance, a few things struck me as the panel worked through the process of collecting and analyzing the most recent research concerning alcohol use and our health.

Why alcohol guidelines trend downwards over time: Improvements in evidence

For one, our work found that alcohol use is more harmful for our health than was previously thought. Alcohol advice hadn’t been updated in Canada for more than ten years and the biggest changes during that time were about the quality of the evidence available. Over time, scientific studies have gotten better and better at measuring the true impact of alcohol use on our health, while controlling for other related behaviours and factors: in a nutshell, getting at causation as opposed to correlation. More recent summaries of this health evidence, like the UK’s guidelines that were published in 2016, have all shown the same thing: alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought. Due to this, suggested drinking limits in every country have tended to be revised downwards over time.

Another takeaway was that the most-straightforward advice regarding alcohol use is that no matter how much we drink the main message is the same: “Drinking less is better for health.” Health risk from alcohol use starts with one drink and goes up from there. Of course, the risk associated with a single drink is very small, but still this advice is universal. The rest of the guidance is then about providing information about how quickly the risk increases in a way that helps us all make choices about whether, or how much, to drink.

Similarities and differences between alcohol advice in Canada and the UK

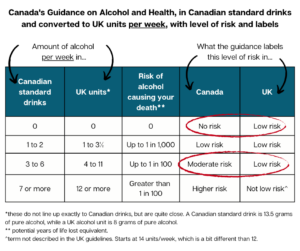

For these first two points, it doesn’t matter what country we’re in. But this is Canada’s guidance after all, so to understand more of the advice we have to learn about some differences between the UK and Canada in terms of the language we use to describe our alcohol use. First, the way our two countries communicate measures of pure alcohol is different. In the UK, alcohol units are used and are equal to 8 grams of pure alcohol. In Canada, we use standard drinks, which are 13.5 grams of pure alcohol. So a Canadian drink is 70% larger than a UK unit and this is important when discussing the new guidance for those in the UK.

Now some easy homework for you as readers! Please open the public summary of the new Canadian advice. Focus on the main graphic about alcohol consumption per week. Notice the four risk zones presented – the new guidance describes a continuum of risk, instead of binary guidelines that we are either above or below. This has the advantage of allowing us to place ourselves along this continuum of risk and encourages us to think about whether reducing our use is necessary and what might be a reasonable and achievable reduction given our personal situation.

Starting with this graphic, let’s translate Canada’s advice to UK alcohol units. Canada’s no risk zone is clear – to avoid any risk from alcohol use, we would avoid using alcohol. Surprisingly, UK guidelines don’t mention this way to avoid risk and improve health. Canada’s low risk zone is up to 2 Canadian standard drinks per week (about 3.5 UK units), the moderate risk zone is up to 6 drinks per week (about 11 UK units) and the higher risk zone is above 7 drinks per week (above 12 UK units).

The conversions between Canadian drinks and UK units are shown in the table above. When we present it this way, we see there isn’t such a big difference between Canada’s guidance and the UK’s guidelines, but two points stand out (see the red circles in the table). First, Canada describes a no risk zone that relates to not using alcohol; this could be important as about 20% of adults and about 40% of people in Canada and the UK don’t drink at all in a given year. We might ask why health guidelines would be created for only about half the people in a country?

Next, the zone which Canada’s guidance labels “moderate risk” is included in the UK “low risk” zone. The labels used for these risk zones are subjective, but in Canada’s guidance everyone can look at the figure in the public summary to choose a level of risk they feel is appropriate. Indeed, the reason Canada presented more than one zone was that the committee didn’t want to choose what a level of “acceptable risk” was and so presented more information about alcohol and health rather than less.

Health advice is often given that describes a level of exposure that would result in an increased risk of dying prematurely of about 1 in 1,000. From the table, we see that this corresponds to the zone going up to 3½ UK alcohol units per week. But alcohol has sometimes been given special standing and permitted to convey a risk ten times higher – an increased risk of 1 in 100 – and this would correspond to up to 11 UK units per week.

This was the biggest difference used to communicate the guidance in Canada, as compared to other countries such as the UK and Australia. In Canada, the health risk of alcohol was placed on a level playing field with other behaviours and exposures, the committee didn’t feel that a study intended to promote public health should describe a drinking zone that conveyed a risk of premature death of up to 1 in 100 as “low risk.” By providing a continuum of risk, we hope that people are better able to place themselves along this continuum and consider reducing their risk if they feel it’s appropriate.

Beyond advice to individuals, the Canadian guidance also provides suggestions to governments and regulators designed to support Canadians in adopting this new advice, if they choose. The final report suggested that government should consider mandating labelling requirements on alcoholic beverages that would include the number of standard drinks in a container. Clearly, it’s difficult for all of us to follow advice given in standard drinks if we don’t know how many standard drinks are in our beverages.

Regardless of which country’s guidelines you’re reading, there are consistent takeaways. Drinking alcohol is more harmful for health than was previously thought and so it may be time to rethink the way we drink. All types of alcohol – beer, wine, hard spirits/liquor – convey the same amount of risk based on how much pure alcohol they contain, so learn what a standard drink (or alcohol unit) is and, if you drink, count your drinks. Canada’s new advice provides risk information based on how much alcohol we use in a week. Have a look at the new Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health if you’re interested in learning more.

Written by Dr Adam Sherk, Scientist, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

COI Declaration

I have received grant and/or contract funding, or my institute as has received grant and/or contract funding that was used to pay my salary and benefits, from the following government organizations that are involved in the wholesale and/or retail sale of alcohol/ethanol products:

- Systembolaget, Sweden

- Alko, Finland

- Liquor and Cannabis Regulation Branch and Liquor Distribution Branch, British Columbia, Canada

I have never received funding from any private alcohol/ethanol producers, companies, distributors, advertisers, wholesalers or retailers.