In January 2022, I wrote that there were no signs of the ‘return to normal’ in drinking patterns that was hoped for in the wake of the pandemic. A year on, just as how questions about drinking cultures in Whitehall and Downing Street and the ‘partygate’ inquiry have dragged on, many of the same concerning trends in alcohol consumption have persisted, too.

Last year, the cost-of-living crisis was looming. Now, inflation is at a 40-year high, with enormous price increases for energy, and inflation for food and non-alcoholic drinks is almost 17%, compared with 3.5% for alcohol.

In the world of alcohol policy, all the main stories of 2022 can be found in IAS’s Year in Review edition of the Alcohol Alert. This post is a recap of trends in and new data about alcohol consumption and harm in 2022.

What has happened?

After a year’s hiatus due to the pandemic, the Health Survey for England returned in 2021 and was published at the end of 2022. Due to changes in survey methods, trends are not comparable with previous years, but headline findings for alcohol are:

- Two out of ten adults (21%) had not drunk alcohol in the last 12 months

- Nearly six out of ten (57%) adults drank at levels which put them at lower risk of alcohol-related harm (14 units or less each week)

- Two out of ten (21%) adults drank at increasing or higher risk of alcohol-related harm (more than 14 units per week)

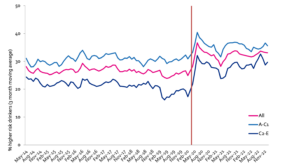

The Alcohol Toolkit Study in England shows that increasing and higher risk drinking (a different measure than used in the Health Survey for England) remain above pre-pandemic levels. In 2019, around one in four adults were drinking at increasing and higher risk levels. Through 2022, it was one in three:

Figure 1: Increasing and higher risk drinking from Alcohol Toolkit Study, 2014-2022

Regarding harm from alcohol, the higher levels of risky drinking have already led to more people in alcohol treatment and more emergency admissions for liver disease.

Last month, 2021’s alcohol-specific deaths figures for the whole of the UK were released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). In 2021, there were 9,641 alcohol-specific deaths, the highest number on record. This was 7% higher than 2020’s previous high, and 27% higher than 2019.

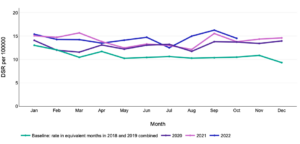

Provisional ONS data up to October 2022 for England only are available from the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. These show that alcohol specific deaths are still well above 2018-19:

Figure 2:Monthly trend in mortality for all alcohol-specific conditions in England – all persons

Last July, IAS and HealthLumen published our COVID Hangover study, funded by the National Institute of Health Research, which modelled the longer-term impact on health and healthcare up to 2035.

We projected up to 10,000 additional deaths and extra healthcare costs of up to £1.2bn. A similar study using the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model had similar findings.

What does 2023 have in store?

At IAS, we will soon enter our 2023-26 Strategy period with new areas of focus soon to be announced.

The context is challenging, but there are opportunities to try and reverse these trends. This year brings a prevention inquiry from The Health and Social Care Committee, a major consultation on alcohol marketing regulation in Scotland, the continuing evaluation of minimum unit pricing in Scotland ahead of the sunset clause, as well as new alcohol duty structures being introduced in August 2023.

These trends do not seem to be going away on their own. They need a response, and there is good public support for many evidence-based policies.

Written by Dr Sadie Boniface, Head of Research, Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.