In England, local authorities oversee the sale of alcohol and have significant powers to try to reduce alcohol-related harms. One such power is the Late Night Levy.

The levy is an intervention that aims to minimise the harmful social effects of late night drinking. Alcohol retailers (including shops, bars/clubs, restaurants and clubs) who are open after midnight are charged a fee (£299 – £4,400 per year)[1]. The money raised from the levy must then be split between the licensing authority and the police service, with a minimum of 70% going to the police. Beyond this, each local authority has significant discretion in how they spend the revenue. Newcastle City Council introduced the first Late Night Levy in 2012 and it’s now in operation in ten local authorities in England.

The study

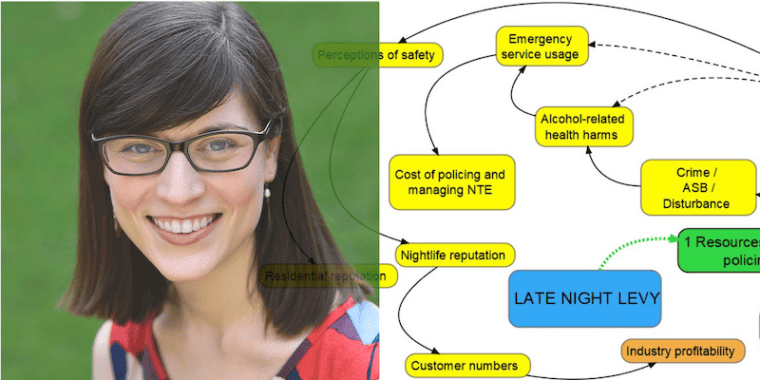

We conducted the first known evaluation of the Late Night Levy. Our evaluation was conducted in one London local authority which has a mix of residential and commercial properties. It hosts a vibrant night life which attracts visitors from across, and beyond, London. The local authority implemented the levy at the end of 2014 and has used the revenue to fund a private four-person community safety patrol, as well as additional night-time police officers. We used a systems approach to conduct the evaluation in two phases.

In the first phase, we wanted to understand how different groups thought the levy might lead to changes in the local area. To do this, we analysed national and local authority documents and responses to a local consultation. From these, we identified four hypotheses about how the levy may create changes.

In the second phase, we followed the hypotheses in the first two years after the levy came into effect. To do this, we interviewed police and community safety officers, local authority licensing and public health employees and people drinking in pubs. We also observed the levy-funded community safety patrols. Finally, we analysed annual levy reports from the local authority and the community safety company. Using these data, we explored the extent to which the four hypotheses played out in practice.

What did we find?

Hypothesis 1:

Those that were supportive of the levy believed it would raise additional money that could be used to make the night-time economy safer.

Once the levy came into effect, we found that enough money was raised to fund extra night-time police officers and a four-person community safety patrol. These officers provided welfare checks on members of the public and tried to prevent anti-social behaviour and violence. For example, community safety officers would help reunite people on their own with their friends and tip out the drinks of groups drinking on the street.

The community safety patrol also worked directly with the door staff and managers of pubs, bars and clubs. While many of these venues were initially against the idea of the levy, the patrol officers tried to develop relationships with them. They did this by visiting them frequently and by assisting door staff when managing difficult patrons.

Over time, the community safety officers and police thought many venues became ‘more responsible’ in terms of better managing patrons’ behaviour and calling the community safety officers when they needed additional support. In addition, in the first year of the levy, the local authority reported a large reduction in alcohol-related crime (17%) and violence (14.4%) after midnight, although they assumed this was not caused only by the levy.

Hypothesis 2:

The second hypothesis we identified was put forward by local business owners who opposed the levy. These owners argued that if the levy was brought in, that they would stop supporting voluntary local initiatives. For example, many business owners said they would vote against the Business Improvement District (BID) the next time it came up for a vote because they wouldn’t have the funds to pay both the levy fee and the BID fee.

We found that these concerns were not realised in the first two years after the levy came into effect. During this time, the BID came up for a vote and it was not only renewed, but it was expanded. Local business owners reported using both BID and levy-funded police and community-safety services.

Hypotheses 3 and 4:

Local businesses and organisations that support them (e.g. trade organisations and pub companies) were opposed to the levy. They argued it would force many businesses to reduce their opening hours and close by midnight (hypothesis 3). They also thought some venues might have to close entirely because the levy would make them no longer profitable (hypothesis 4).

Businesses and trade organisations argued the changes to businesses’ opening hours would cause an increase in anti-social behaviour or crime as patrons spilled out onto the streets at the same time. Those opposed to the levy argued it would make the local area less attractive to visitors, residents and business owners.

After the levy came into effect, approximately 25% of businesses changed their hours to shut before midnight or closed entirely. Of these, only a small number permanently closed. While some venues did close at the same time, this was not associated with a significant clustering of closing times. The area continued to be known for having diverse and vibrant night life.

As a result of all of the factors described above, the local authority viewed the levy as successful and decided to keep it in place.

Broader considerations

This evaluation shows some of the ways that the levy creates change within the night-time economy. It provides valuable evidence to refute some stakeholder claims, particularly those from the alcohol industry, about possible negative consequences of the levy. This is important since most of these claims were made without the support of any research evidence. Despite not having evidence, industry lobbying can affect a local authority’s decision to implement a specific policy. We therefore hope that the findings from this study, particularly those that show the levy did not lead to a clustering of closing times or a reduction in diversity of night-time businesses, are of use to other local authorities considering the levy.

We also found that discussions about reducing alcohol-related harms through the levy focussed almost exclusively on preventing anti-social behaviour, crime and violence caused by intoxicated individuals. While these are important alcohol-related harms to reduce, this framing mirrors that used by the alcohol industry. That is, the alcohol industry also encourages minimising the harms associated with alcohol consumption, rather than seeking opportunities to reduce alcohol sales and consumption in the first place. Ultimately, efforts to reduce alcohol harms must focus both on reducing alcohol sales and the harms that occur after alcohol is consumed.

Written by Dr Elizabeth McGill, Dr Dalya Marks, Professor Mark Petticrew and Professor Matt Egan, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

[1] The amount of the fee is nationally-determined and based on the premises’ rateable value and the extent to which it is alcohol-led.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.