Introduction

Alcohol consumption is a substantial and growing contributor to ill health and premature mortality worldwide, with 2018 WHO estimates suggesting that alcohol was responsible for 14% of global deaths in people aged 20 to 39 years old in that year. To address these harms, WHO has suggested that governments implement a range of alcohol control policies, including measures to regulate alcohol labelling and marketing.

One policy that has received increasing attention in recent years is health warning labels on alcohol products. These are regulations that require alcohol companies to affix a label conveying information on the harms related to alcohol consumption on alcohol bottles. They are much like those now commonly placed on tobacco packs and, increasingly, calorie dense foods, as depicted below.

Although alcohol health warning labelling can be effective in discouraging consumption, most governments – including the UK – do not require them. Instead, bottle labels typically have few health-related requirements. The UK requires an image designed to discourage drinking when pregnant, for example (see left hand image below). These are small and are not prominently positioned and are not coloured, unlike food and tobacco warnings which are intentionally coloured to grab consumers’ attention (see the central and right hand images below). They are also not targeted at the general population, and do not contain health information about the effects of alcohol consumption. Alcohol labels are therefore often designed according to the branding and design a company may see as appealing to its target market – that is, whatever design a company thinks will help sell its products, regardless of their risks.

Although alcohol health warning labels are a promising approach to promote health and bring alcohol regulation in line with other harmful commodities, industry groups have been vehemently opposed to the measures. Yet, this opposition often takes place behind closed doors and, as our new analysis in The Lancet Global Health shows, in unexpected fora. We found that the alcohol industry appears be using a major international trade forum – the World Trade Organization – to stall implementation of alcohol health warning labelling policies.

The World Trade Organization and Technical Barriers to Trade

Our study looked specifically at the influence of the alcohol industry in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Committee at the WTO. This is a key forum at WTO which governs an international trade agreement that seeks to prevent WTO members from introducing unnecessary obstacles to international trade (the ‘Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement’).

Measures such as labelling or product content limits that are designed to protect health are regularly discussed in this forum because they introduce trade costs. At the same time, the agreement does recognise the protection of public health as a legitimate policy objective, so discussions at the TBT tend to centre on whether a policy is necessary and can achieve that objective, or whether an alternative should be introduced instead.

In discussions at WTO, member state representatives regularly query and challenge policies proposed by other members. Following such comments, WTO members have strong incentives to delay, water down, or abandon policies, because failing to do so can result in enormously costly legal battles. As just one example, it was reported that the Australian government spent $39 million defending its plain tobacco packaging legislation in legal battles about the measure, including a WTO dispute.

TBT Committee meetings can therefore be a useful forum for industry to try to stall policies targeting their products by asking WTO member representatives to raise concerns and challenges to a policy on their behalf. Indeed, there is evidence that the tobacco, food, and pharmaceutical industries have lobbied WTO representatives to raise their concerns about policies targeting their products at WTO.

We sought to assess whether or not the alcohol industry may be doing the same.

Analysing the alcohol industry’s influence at WTO

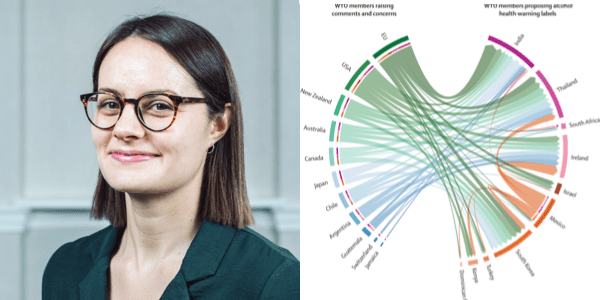

We examined discussions related to proposed alcohol labelling policies at the TBT Committee from 1995 to 2019. Ten policies on stricter alcohol labelling were put forward by Thailand, Kenya, the Dominican Republic, Israel, Turkey, Mexico, India, South Africa, Ireland, and South Korea. We analysed comments raised by WTO representatives on these policies and sought to identify any explicit references to industry demands within WTO representatives’ statements.

However, there is no obligation for WTO representatives to disclose the genesis of their comments, including whether they originated from industry. We therefore also compared all arguments at WTO against a list of arguments regularly advanced by the alcohol industry to stall policy in domestic policy debates. We noted which common industry arguments appeared in WTO representatives’ statements, and how often they were expressly attributed to industry.

We found that 55% (117/212) of WTO member statements included arguments identified as coming from the alcohol industry. However, only 3% (7/212) explicitly stated they represented industry interests.

The industry rhetoric repeated at WTO acts to downplay the extensive harmful effects of alcohol use and to deny the science supporting alcohol labelling. In 22% (46/212) of the statements, for example, WTO members used arguments that deflect attention from alcohol-related harms and minimise alcohol’s negative impacts. For example, instead of acknowledging health harms to the whole population, alcohol-related harms were described as arising from excessive or problem drinking only, or only applying to certain populations and settings, such as underage, drink driving, or pregnancy. Meanwhile, moderate drinking was portrayed as having beneficial effects. These are all common refrains from industry in domestic settings.

Suggestions to pursue alternative policies addressing alcohol-related harm were also present in 7% (15/212) of statements. Just as the industry commonly argues in domestic settings, WTO representatives called for policies such as information and awareness campaigns that do not directly regulate the alcohol industry’s products. For example, the EU urged Kenya to reconsider proposals because “education and information activities seemed to be appropriate means to address the public health objective pursued”. We identified other examples of industry rhetoric, for example where WTO representatives questioned the scientific evidence behind the policies, e.g. refuting the claim that alcohol is carcinogenic.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our findings indicate that WTO may be serving as a key forum for alcohol industry influence over alcohol policies on a global scale. However, industry influence appears to be far more widespread than is currently being disclosed, with very few arguments explicitly referencing industry demands. It’s also possible that some of the industry’s influence via WTO is indirect where, for example, WTO representatives are repeating industry rhetoric they’ve been exposed to elsewhere (e.g. in other policy consultations or print media).

The evidence that WTO is yet another forum for alcohol industry influence, direct or indirect, suggests that much more transparency is needed at WTO to ensure that any vested interests are clearly disclosed. Furthermore, as Maristela Monteiro and Zila Sanchez pointed out in their commentary on our paper, our study suggests that WHO should work with all UN organisations, including WTO, to minimise the negative effects of vested interests and to achieve a unified position on placing health and equity at the centre of development. Governments can also unite to develop clear rules to disclose vested interests and prevent them from having an influence on the efforts to reduce alcohol consumption and related harms via trade fora.

Written by Dr Pepita Barlow, Assistant Professor of Health Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.