Obesity is one of the most serious and burdensome public health challenges faced worldwide. In the UK, around 1 in 3 adults live with obesity. While the development of obesity is extremely complex, ultimately, it is caused by prolonged, excessive energy intake (calories).

Alcohol has been proposed as a contributing factor towards obesity for several reasons. Firstly, like other drinks, alcohol doesn’t trigger feelings of ‘fullness’ to the same extent as solid foods – it’s pretty easy to have a few drinks and still eat a full meal. Alcohol is also very energy-dense and contains a lot of calories even at small volumes (e.g., one medium glass of wine = 140 calories, which is around the same calories as three KitKat chocolate fingers). Further, when consumed with food, alcohol prevents dietary fat from being ‘burned’, therefore, this fat is more likely to be converted to body fat. And finally, alcohol has psychoactive properties that seem to make us eat more.

What we wanted to find out

In our recently published article, we consolidated and appraised the research on:

- alcohol and calorie intake;

- alcohol and body weight;

- the interconnectedness of food and alcohol in real life.

Rather than looking at every individual article, where we could we looked at previous reviews where researchers had already pulled together similar studies. This approach allowed us to examine the body of research ‘as a whole’.

Does drinking alcohol increase calorie intake?

We found a recent review that pulled together laboratory studies looking at alcohol’s short-term effect on calorie intake. The body of research showed that, compared to alcohol-free drinks, alcohol increases calorie intake by around 250 calories per day. Some of these extra calories come from the alcohol itself, and some come from alcohol-related eating. This shows that when we drink alcohol a) it is added, rather than substituted into the diet, and b) we appear to eat more food.

Does drinking alcohol lead to weight gain?

Given that alcohol increases calorie intake in the short-term, it is logical that drinking more and drinking more often would lead to weight gain over time (Figure 1). Only a few longer-term experimental studies have investigated this. In these experiments, participants in the experimental condition drank a certain amount of alcohol each day (e.g. 300 mL wine), while participants in the control condition abstained from alcohol or drank alcohol-free alternatives. Virtually all of these studies found no difference in weight between the two groups after a few weeks to months.

We found several previous reviews bringing together dozens of observational studies on alcohol and weight. The findings were mixed, and even contradictory. Some studies showed that higher alcohol intake was associated with higher weight, some showed the opposite, and others found no relationship. To complicate things further, findings broken down by sex and type of alcoholic drink (e.g. beer vs. wine) were also contradictory. The most consistent finding was that binge/heavy drinking was associated with obesity.

Figure 1. The proposed causal pathway from alcohol intake to weight gain.

Food and alcohol in real life

We found very few studies looking at how drinking and eating behaviours interact in real life. Most studies were conducted in adolescents/young adults and found that interconnected food and alcohol intake are an important part of socialising and identity. Also, younger people suggested that weight gain during college was due, in part, to drinking and alcohol-related eating.

Much research shows that the consumption of alcohol and unhealthy foods are influenced by many of the same factors. Both products are very easy to access, relatively cheap, socially acceptable, and heavily advertised/marketed. Greater alcohol outlet density is related to higher alcohol intake, while greater takeaway outlet density is related to higher rates of obesity. In summary, physical, economic, and political environments make it too easy to overindulge in both.

Bringing it all together

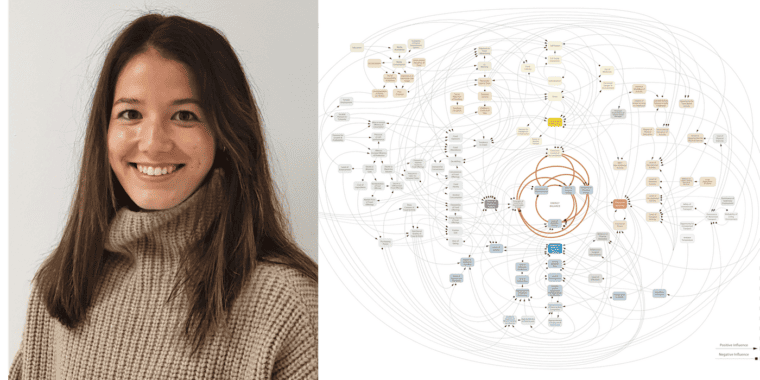

In short, the research is just too inconsistent to be able to make confident conclusions about the relationship between alcohol and weight. One of the main reasons for this is the complexity of body weight (Figure 2) and the type of studies conducted. Most studies used a cross-sectional (snapshot) design; people are surveyed at one point in time and asked about their weight and alcohol intake. This approach oversimplifies a complex relationship and doesn’t account for all the other factors that influence weight, especially those that can mitigate against weight gain.

For example, studies have shown that greater alcohol consumption is associated with greater physical activity levels which explains why some studies found no association between alcohol and weight. It also depends on what aspect of alcohol intake is measured; do you look at drinking frequency, volume, or pattern? Is this measured through a survey or a food diary? And of course, there’s the issue of people underreporting alcohol intake, either intentionally or unintentionally.

The reality is, it is near impossible to show the effect of one drink (or one food, or one nutrient, or one behaviour, or one meal…) on body weight. Rather than doing more of the same cross-sectional studies, we need innovative research that captures relevant behaviours, influences, and experiences as they occur in real life.

Figure 2. ‘Systems map’ showing the interaction between various factors and their influence on body weight.

A problem shared is a problem halved

Given commonalities between Big Food and Big Alcohol, and that eating and drinking behaviours are influenced by many of the same factors, effective policy solutions are likely to overlap. For example, taxation of fat content in foods is akin to minimum unit pricing for alcohol. Reformulation strategies to produce low-fat food products is similar to producing low-alcohol drinks. Food and alcohol policy makers may benefit from collaboration and knowledge exchange, and joined-up lobbying may be more effective than isolated efforts.

Next steps for research

There are not many studies looking specifically at policies aiming to reduce calories from alcohol e.g. including calorie content on alcohol labels, the role of low-alcohol alternatives, and moderating portion size. More studies are needed to find out how effective these strategies are in real life, and importantly, how they impact existing socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol use, obesity and dietary intake.

Written by Mackenzie Fong, Research Fellow, NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (North East North Cumbria), Newcastle University.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.