Results from the Northern Territories Alcohol Labels study in Canada

Three years after the launch of this world-first study, the main results from the Canadian Northern Territories Alcohol Labels study, led by Erin Hobin (Public Health Ontario) and Tim Stockwell (University of Victoria’s Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research), were published as part of a special section of the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

Why alcohol warning labels?

As described in this recent blog post outlining some of the study’s early findings, despite alcohol’s worldwide popularity, there is generally limited knowledge that drinking increases the risk of seven different types of cancer recognized by the World Health Organization as being caused by alcohol. Posting warning labels directly on containers is a potentially cost-effective way to improve consumer awareness about the health risks of alcohol while increasing support for other well-established alcohol control measures for reducing consumption and related harms, however, there have been no real-word evaluations of labels designed consistent with the best available evidence until now.

Why do this study?

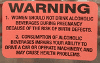

The aim of this study was to test if, in a real-world setting, labelling alcohol containers with health messages could support safer, more informed alcohol consumption. Partnering with the government-run Yukon Liquor Corporation, the research plan was to place new health labels on all alcohol containers sold in the main liquor store in the capital city of Whitehorse, Yukon, for an eight-month period. The impact of these labels on consumers was assessed by examining alcohol sales data and consumer responses in Whitehorse compared to other regions within Yukon and to the neighbouring Northwest Territories (NWT), where no new labels were added. Yukon and NWT were ideal jurisdictions to test new warning labels because both are the only regions in Canada to require a post-manufacturer label on containers since 1991. These longstanding labels cautioned consumers about drinking while pregnant and in NWT there are additional label messages about drinking when driving and operating machinery and general health problems, similar to the label in the US (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Alcohol warning labels in place since 1991

Yukon |

(actual size 2cm x 2cm)

NWT |

(actual size 3.2cm x 5cm)

How were the new labels different?

The new alcohol labels that formed part of the research study were larger than the previous ones, brightly coloured and ran three rotating messages (Figure 2): 1) a cancer warning, 2) Canada’s national drinking guidelines, and 3) the number of standard drinks in various containers. Label content, size and format were informed by research evidence as well as consultations with local and international health experts and community stakeholders.

Figure 2: Intervention alcohol warning labels 2017

|

(actual size 5cm x 3.2cm)

What data sources and methods were used to evaluate the impact of the new alcohol labels?

1) Official alcohol sales data: The Yukon Liquor Corporation provided the research team with detailed monthly sales data for products that were either labelled with the new warnings or were exempt from the labels. These data covered 28 months before the new labels were first introduced and 14 months afterwards, separately for Whitehorse and for other rural areas of Yukon. Comparable sales data were obtained from the Northwest Territories Bureau of Statistics for the whole of NWT for same time period. Researchers used official census data on the number of people living in each of these regions to calculate the average consumption of pure alcohol per person, per month in each region.

2) Longitudinal surveys with adult drinkers: Three waves of survey data were collected in Whitehorse and Yellowknife: a baseline survey four months before the intervention began in Whitehorse (May-June 2017) and at two time periods during the eight months the new alcohol labels were in place (February-March 2018 and June-July 2018). A total of 2,049 adults who reported drinking alcohol in the previous month were recruited after shopping at the government operated liquor stores in both cities and followed longitudinally over the duration of the intervention. These surveys asked customers if they had noticed the new labels, were aware of the new label messages and if they had modified their drinking as a result.

What did our evaluation find?

- About 300,000 labels were applied to 98% of alcohol containers sold in the liquor store in Whitehorse over the study period.

- Prior to the new labels, consumer awareness of alcohol’s cancer risk, of Canada’s national drinking guidelines, and of the number of standard drinks in containers was low.

- After the new labels were introduced in the main liquor store in Whitehorse, consumer awareness of alcohol’s cancer risk and Canada’s national drinking guidelines increased in Whitehorse compared to Yellowknife, where no new labels had been added.

- Consumers who became aware that alcohol can cause cancer were twice as likely to express support policies to increase the price of cheap alcohol as those who were unaware of the alcohol-cancer link.

- Analysis of the sales data showed that average alcohol consumption in Whitehorse decreased by 6% during the study period compared to NWT and neighbouring regions in Yukon.

- Average consumption of alcohol sold in labelled alcohol containers decreased by 7% while average consumption of alcohol from the many fewer unlabeled containers increased by 7%.

- Expert legal analysis showed that the Canadian alcohol industry lobbyists statements about the legality of alcohol warning labels was flawed. Instead, the analysis showed that Canadian territories and provinces have a duty to inform consumers about the health risks of a product they are involved in distributing, promoting and selling. Failure to adequately inform consumers exposes governments to future civil lawsuits as happened with tobacco.

- The majority of news stories supported use of the labels in Yukon but many quotes and statements from alcohol industry representatives in the media coverage distorted or denied the link between alcohol and cancer.

What are our overall conclusions?

The findings of this research demonstrate that highly visible, brightly coloured alcohol warning labels are an effective way of communicating important information about alcohol’s health risks and guidance for low-risk drinking. The alcohol industry has opposed warnings on health effects, such as cancer, which highlights the importance of compulsory alcohol labelling to ensure that consumers are well informed about risks if they choose to drink alcohol.

What are our policy recommendations?

We recommend that all alcohol containers be required to carry rotating health warning labels, including 1) health risk information such as a cancer warning, 2) national drinking guidelines, and 3) the number of standard drinks per container. This can be achieved variously at different levels of government but requires public health champions and public support to be successfully implemented and to push back against industry interference.

We will discuss the experience and implications of the alcohol industry interference in the Northern Territories Alcohol Study in the next IAS blog post [link].

Written by the Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study Research Team, co-led by the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. For further information about the study, media coverage, infographics and peer-reviewed manuscripts and conference abstracts, please visit: https://www.alcohollabels.cisur.ca/

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.