It seems the South African Government, now more than ever, is willing to consider a re-evaluation of the liquor regulatory environment

South Africa’s official response to COVID-19 began 15 March 2020 with the announcement by President Cyril Ramaphosa of a national State of Disaster in terms of the Disaster Management Act of 2002. One of key provisions of the State of Disaster was that liquor at on-consumption and off-consumption outlets could only be sold and/or consumed between 9am and 6pm Monday to Saturday and 9am – 1pm Sundays and public holidays. Gatherings were restricted to 50 people at a time, including in establishments where liquor was sold. Restaurants that sold liquor could remain open after 6pm, still subject to the 50-person rule, but could not continue selling liquor.

Anecdotal evidence for the week following was that there was a reduction in transport emergencies involving cars, motorcycles and pedestrians of between 25% and 50%. Ambulance services reported a dramatic drop in assaults, stabbings and accidents at work in that period, especially over the weekend of 21-22 March.

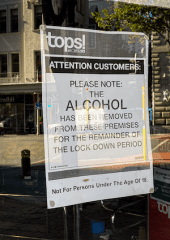

The initial COVID-19 restrictions were replaced a week later with a full national lockdown requiring most businesses to close and the population to stay at home. Schools and universities were shut and access to public places like parks was forbidden. As in most other countries in the world, restaurants, bars, nightclubs and other places of entertainment had to stop operating. However, South Africa did not adopt the global practice of allowing off-consumption sales of liquor, choosing instead to ban completely the sale and transportation of liquor.

This was done largely for public health reasons. Government was worried that drinkers would be less inclined to observe the basic protocols needed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus: physical distancing, cough etiquette and hand hygiene. It was also believed that banning access to liquor could limit the incidence of inter-personal violence – of particular concern was the potential for an increase in domestic violence, given that the lockdown meant that people would be in enforced proximity with each other under stressful circumstances. Women (and their children) who were already subject to gender-based violence in their relationships would be particularly at risk, especially if liquor was in the mix.

Furthermore, with less liquor-related trauma and non-communicable disease cases presenting at hospitals, bed space would be freed-up for the anticipated COVID-19 cases that would need to be accommodated when the pandemic peaked in South Africa. The Minister of Police was also strongly of the opinion that the liquor ban would lead to a dramatic reduction in crime.

Reaction to the ban has centred around issues such as the alleged infringement of personal rights, perceived over-reach by the state, a possible increase in illicit liquor production, the creation of a black market in commercial liquor, looting of liquor outlets, and the unintended suffering of people with liquor addictions. While there have been threats by the liquor industry to take the government to court, this has not happened. Furthermore, the government has demonstrated a determination to maintain the ban in the face of such threats and other criticisms, particularly with respect to the economic impact of the ban. This has been raised with respect to the possibility that small and medium-sized businesses might be forced to close down, resulting in wide-spread retrenchment, to the loss of excise tax on liquor sales (and tobacco sales, also stopped for health reasons), and insecurity and poverty for those working in the subsistence liquor sector.

Since the lockdown began, the drop in crime, assault cases and presentations to the emergency rooms at hospital has been sustained. In a newspaper report published on 25 April, Minister of Police Bheki Cele released statistics comparing the period 29 March to 22 April 2019 and 27 March to 20 April 2020. These indicated a 72% drop in reported murder cases as well as an 82% decrease in reported rape cases. Attempted murder cases went from 1,300 to 443, rape cases 2,908 to 371, gender-based assault cases 11,876 to 1,758, and aggravated robberies 6,654 to 2 022. Other crimes that decreased include carjacking (80.9% decrease), robbery at non-residential premises (65.5% decrease) and robbery at residential premises (decreased by 53.8%). Pointing out that many cases of domestic violence involved liquor, Cele said the number of reported cases had gone down by 69.4%. Parry, Matzopoulos and Nicol have also reported a two-thirds reduction in hospital admissions since the lockdown began.

There are two important issues to consider going forward.

Firstly, the primary impact of COVID measures has been to reduce the availability of liquor, one of the ‘best buys’ of the WHO Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. However, the true role of the ban in reducing liquor-related harms is difficult to assess under lockdown, given the lack of freedom of movement which also contributes to the welcome reduction in crime, road crashes and hospital admissions. Once restrictions begin to be lifted – the government has indicated there won’t be a sudden return to ‘normality’ – it will be easier to undertake meaningful research and produce more compelling evidence of the benefits of reducing availability on a more permanent basis.

Secondly, it is critical to use this opportunity to advocate for a new ‘normal’, for a liquor distribution and consumption policy which takes what has been learned from the time of COVID and applies it to ensure a sustained reduction in liquor-related harm. As Prof Charles Parry pointed out here, under ‘normal’ conditions, liquor kills around 171 people per day in South Africa. Other studies have shown that the country loses billions as a result of the tangible and intangible costs of liquor-related harm. But it seems that the South African Government, now more than ever, is willing to consider a re-evaluation of the liquor regulatory environment. What researchers and civil society will need to do is ensure that this happens and that, post-COVID, there are revised laws which give proper effect to the new national Liquor Policy of 2016 which acknowledged the need to address all three of the WHO ‘best buys’, that of reducing availability, increasing prices, and restricting or banning all forms of marketing.

Written by Maurice Smithers, director of the Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance in South Africa (SAAPA SA), and Professor Charles Parry, director of the Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Research Unit at the South African Medical Research Council.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.