Natasha Clarke and Gareth Hollands on an interesting experiment into a curious phenomenon

The size of wine glasses that are used in bars and restaurants varies considerably – from the modest ‘Paris Goblet’ holding 190ml, to glasses for red wine capable of holding half a litre, that are often favoured in restaurants. The amount wine glasses can hold has also changed over time, with the only study to date that has examined this finding an almost seven-fold increase in their size from 1700 to 2017 – from 66ml to 450ml. In just the last 25 years, glasses have almost doubled in size, from 230ml to 450ml. Pricing, automated technologies for making larger, more robust glasses, and the role of glasses in the drinking experience are some likely explanations for this. But what impact does wine glass size have on how much we drink?

In 2015, we worked together with an establishment in Cambridge, with separate bar and restaurant areas, to run the first study to examine this. They were serving wine in a 300ml glass. We purchased glasses of the same design but that were smaller (250ml), or larger (370ml) than their usual glasses. We changed the glass size used every two weeks, for a period of 16 weeks in total. This meant that for two weeks they served the wine just one glass size only – while keeping the amount of wine they served in each glass the same. We then compared sales for wine when served in each of these three glass sizes. When the larger glasses were used, sales increased by almost 10%. We repeated this study a number of times in other bars and restaurants in Cambridge between 2015 and 2018. We found that larger wine glasses sometimes increased wine sales but not always, with the overall pattern being hard to interpret.

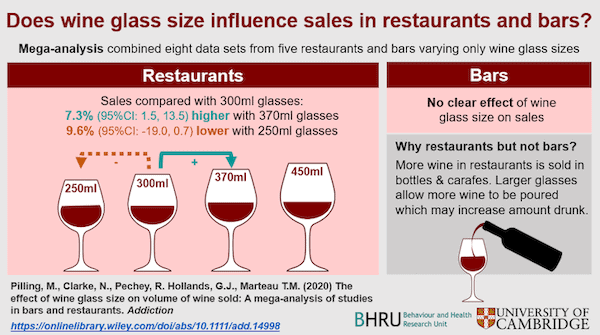

To provide a clearer picture and a robust estimate of the impact of wine glass size on sales we did a ‘mega-analysis‘, bringing together the results of all our previous studies carried out at bars and restaurants. We used 300ml glasses as the comparison size. The overall pattern of results showed that in restaurants, when glass size was increased to 370ml, wine sales increased by 7.3%. There was also a trend to lower sales when smaller 250ml glasses were used. These effects were not found in bars.

Why might glass size have an effect in restaurants but not bars?

One reason is that in restaurants more wine may be sold in bottles or carafes, rather than by the glass, which requires free-pouring by customers or staff. For example, if you are out for a meal, you might get a bottle of wine for the table, which you or restaurant staff would then pour into glasses. In a bar, you might order a fixed portion in a standard measure, such as a 175ml glass of wine. Pouring wine from a bottle or a carafe allows people to pour more than a standard serving size, an effect that may increase with the size of the glass. People may still think of this as ‘one glass of wine’, and drink the same number of glasses as they usually would with a smaller glass and, consequently, drink more wine with larger glasses. It is also possible that wine glass size does affect sales in bars but the effect may be smaller than our study was able to detect.

Does it matter?

If you run a restaurant you might now want to increase the size of your wine glasses to sell more wine. This is exactly what happened after the results of our first study were published. The manager of that establishment told the Wall Street Journal that they removed smaller glasses and used only 370ml glasses.

If you are responsible for public health, you will take a different view. Globally, excess alcohol consumption is the seventh largest contributor to premature death. Our results suggest that reducing the size of glasses might make a useful addition to other well-established approaches for reducing consumption, including increasing the price of alcohol, reducing its availability and curbing its marketing. It’s also likely an intervention that is feasible for implementation, given that in the UK serving sizes are currently regulated by law.

|

Written by Natasha Clarke and Gareth Hollands, Behaviour and Health Research Unit, University of Cambridge.

Natasha Clarke is a Research Associate in the Behaviour and Health Research Unit at the University of Cambridge and works on the Behaviour Change by Design Project (www.behaviourchangebydesign.iph.cam.ac.uk). Natasha obtained a PhD from the University of Liverpool in 2017 which focused on developing interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm by altering cues in the drinking environment, such as glass shape and labelling. Natasha’s current work includes how such interventions can be applied in naturalistic settings. Twitter @Clarke_NC1

Gareth Hollands is a researcher at the University of Cambridge, and an Investigator on the Behaviour Change by Design program (www.behaviourchangebydesign.iph.cam.ac.uk). His research focuses on developing and evaluating interventions that change aspects of physical environments to change health-related behaviors. Twitter @GJHollands.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.