Alcohol has been classified as a Group 1 carcinogen (the highest category of risk) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer since 1988, and causally linked to at least seven types of cancers. Despite these serious health risks, the general public tend to think alcohol is less harmful than tobacco and other substances and largely do not understand it to be a carcinogen, especially in low quantities. Reviews of evidence across 16 countries shows that as few as 13% in some jurisdictions are aware of the link between alcohol and cancer.

Evidence consistently suggests that restricting the availability, marketing and affordability of alcohol are the most cost-effective and easy-to-implement measures for reducing alcohol consumption and harms across the population. However, trying to limit or contain alcohol consumption, even when supported by good evidence, is often resisted by some in the public who see availability, price and convenience of purchase as a societal good. Public approval of alcohol policies is critical for social change. Previous research from Europe and Australia has identified an association between being aware that alcohol is a carcinogen and support for alcohol control policies. Alcohol container labels are one way to communicate harms of alcohol use, including an increased risk of cancer, and are recommended by the World Health Organization.

As part of a larger study designed to develop and test evidence-informed alcohol warning labels as a tool for supporting more informed and safer alcohol consumption, the aim of our paper, Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study, was to examine whether improving knowledge of the link between alcohol and cancer due to the labelling intervention was associated with greater support for alcohol control policies.

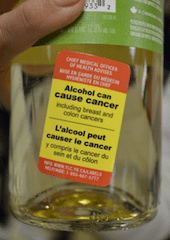

As reported in a January 2018 blog, the alcohol labelling intervention consisted of relatively large, bright yellow labels with three rotating messages: 1) a cancer warning, 2) Canada’s national drinking guidelines, and 3) the number of standard drinks in an alcohol container. Label content, size, and format were informed by evidence as well as consultations with local and international health experts and community stakeholders. Intervention labels were applied to alcohol containers in the one government-operated liquor store in Whitehorse, Yukon (intervention site) between November 2017 – July 2018, and the two government-operated liquor stores in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories (comparison site) did not apply the intervention labels. Participants in the intervention and comparison sites completed surveys assessing alcohol use, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of alcohol, and support for alcohol policies before and at two time points after the intervention was implemented.

After the alcohol labelling intervention, an increase in knowledge that alcohol can cause cancer was observed among 20% of participants. Though levels of support for alcohol pricing and availability policies remained low overall, participants who learned alcohol can cause cancer were 86% more likely to support alcohol pricing policies, particularly a minimum unit pricing policy, relative to those who did not learn the link between alcohol and cancer. Consistent with previous research, knowing that alcohol can cause cancer was also found to be associated with support for alcohol availability, marketing, and pricing policies.

Together, these findings suggest that improving knowledge of alcohol’s health risks, specifically cancer risk, using alcohol warning labels may be an effective strategy for increasing public support for effective alcohol control policies that are currently not well supported, and which, in return, may improve population health.

Written by the Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study Research Team, co-lead by the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.