A declining trend in adolescent drinking has been observed over the past 15–20 years in almost every country in Europe, as well as the US and Australia. The declining trend has been particularly strong in the Nordic countries. The Nordic Welfare Centre (NVC), has recently published a report, What’s new about adolescent drinking in the Nordic countries? The report is an overview of the most recent Nordic research literature on adolescent drinking.

What does Nordic research say about the reason for the declining trend?

Many questions remain regarding the reasons for the decline in adolescent drinking in the Nordics and beyond. The main conclusion is that for the most part researchers are still looking for answers. Nordic studies have, however, found support for the role of certain decisive factors behind the decline in some of the Nordic countries. Firstly, parents know where their adolescents spend their free time and have greater control of it. Secondly, adolescents find it harder to get hold of alcohol. Parents seem to employ stricter rules about alcohol use among teenagers than before. These factors stress the importance of known mechanisms of influencing adolescent drinking: limiting the availability of alcohol, and the role of parents.

Youth culture itself seems to have changed, too, possibly deflating the role of alcohol. Also parenthood seems to have undergone positive changes. However, what these changes are and how they might affect drinking is still under research.

Regardless of the reasons for the change it seems clear that many types of harm may be avoided in adolescence when drinking is less common.

Differences and similarities between the Nordic countries

Youth drinking has been falling across the Nordics. Interestingly, it has also fallen at very different rates to very different levels in different Nordic countries.

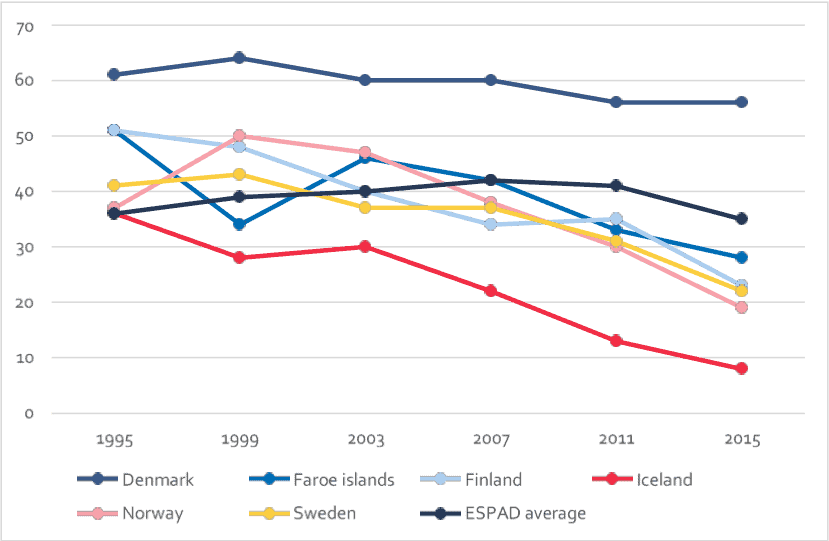

Prevalence (%) of heavy episodic drinking (five drinks or more) during the last 30 days, in the Nordic countries 1995-2015. ESPAD |

This chart shows the proportion of 15–16-year-olds to have engaged in heavy episodic drinking (five or more drinks on one occasion) in the past month, using the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) study of 2015. Two things stand out looking at figures from the ESPAD study. Firstly, in all countries the share of young people who do not engage in heavy drinking or drink at all, has grown. Secondly, the differences between the Nordic countries have grown. In 2015, the percentage of abstainers was 65 in Iceland and 8 in Denmark according to the ESPAD study.

Drinking is nowadays least common in Iceland and Norway, followed by Sweden and Finland. Denmark serves as the ‘Nordic exception’. It is the only Nordic country where adolescent drinking is above the European average and where heavy drinking is still common.

In Denmark drinking and intoxication still seems to play an important role in youth culture and remains relatively common despite the decline (The share of young people who reported intoxication during the last month was 56% in Denmark compared to the European average of 35% according to the ESPAD study of 2015). Denmark also has a lower legal purchase age: 16 for wine and beer, as opposed to 18 in the other Nordic countries and 20 in Iceland.

In Iceland, only 8% of 15–16-year-olds reported heavy episodic drinking in the past month in 2015. Iceland has seen by far the fastest decline among the Nordic countries. This has drawn a lot of attention to the Icelandic effortsto prevent young people from drinking and behaving delinquently based on the assumption that alcohol and drug education should focus on many areas of adolescent lives. Parents are for instance ponderously encouraged to enforce the legal age-limit for buying alcohol and to be more engaged with their children. Curfews are set for 13–16-year-olds and there is heavy state funding for recreational activities.

What do we gain from a Nordic perspective?

Youth drinking has declined in most Western countries, but there are still insights to be had from looking at youth drinking in a distinctly Nordic context. The five Nordic countries have relatively high levels of universal state provision in health, social care, and education, for example, making the countries egalitarian and social and economic differences relatively small. The Nordic states share an alcohol policy which aims to reduce alcohol-related harm by restricting availability of alcohol through opening hours, pricing, age limits, etc. All Nordic countries with the exceptions of Denmark regulate alcohol sales of wines and spirits through state alcohol monopolies.

Studying the Nordic developments separately from other Western countries may suggest what is universal about drinking among young people and which mechanisms are at work regardless of state subsidies, social benefits, or drinking culture. We might also learn what kind of social harms related to youth drinking may be limited by the welfare state or alcohol monopolies.

In spite of the similarities of the Nordic countries there are also some differences also on the policy and judicial level such as differing alcohol policies. Comparing the Nordic differences may pave the way for insights of many kinds.

Preventive efforts should target all young people

In most Nordic countries, a reduction in drinking has been observed among all kinds of drinkers, from light to heavy consumers. Research indicates that both those who drink a lot and those who drink less have started to drink less. Some groups, however, have not followed the trend: drinking has increased in certain socioeconomically deprived groups.

Still, Nordic research shows that not all adolescents that drink hard continue to do so in adulthood, and not all adults who drink too much have done so in their youth. Preventive efforts should thus target entire populations of young people and not just those who drink heavily.

Yaira Obstbaum is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki who wrote the report ‘What’s New About Adolescent Drinking in the Nordic Countries?’ for the Nordic Welfare Centre.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.