On the 9th of May, more than 100 postgraduate research students from the University of Bristol showcased their work at the annual Research Without Borders festival. The public were invited to visit over 70 interactive research stalls and participate in engaging activities designed to stimulate discussion.

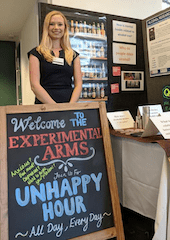

I’m a PhD student working in the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group (TARG) at the School of Experimental Psychology. I transformed my stall into a mock pub to exhibit my research on the relationship between anxiety and alcohol use. I designed a chalkboard sign illustrating coping-motivated drinking, posters explaining how and why TARG conduct research on alcohol and mental health, and activities to make my research on anxiety and alcohol use accessible to different audiences.

I started by introducing different theories on the relationship between anxiety and alcohol use.

- Does anxiety increase alcohol use (positive relationship)?

- Does anxiety decrease alcohol use (negative relationship)?

- Does alcohol use increase anxiety (reverse causation)?

- Is there no relationship?

Visitors and I considered possible biological, social and psychological explanations for these theories. 1. People with anxiety may drink alcohol to alleviate symptoms (self-medication hypothesis). 2. People with anxiety may avoid alcohol if they are socially withdrawn, or concerned about alcohol impeding cognitions and behaviour or damaging health. 3. Heavy drinking may increase anxiety, biologically, or socially via effects on work and relationships. 4. Genetic or environmental factors may increase both anxiety and alcohol use (confounding). In my PhD, I conduct different studies (systematic review, prospective cohort, cross-sectional, experimental) to test whether anxiety is associated with greater alcohol use.

In a second activity, visitors noted reasons why people drink alcohol. They then considered how these reasons corresponded to the four motivational dimensions assessed by the Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised: ‘social’ (to be sociable, to celebrate parties), ‘enhancement’ (because it’s fun, you like the feeling), ‘conformity’ (because others do, to fit in) and ‘coping’ (to forget problems, cope with depression and nervousness). I’m also investigating the role coping motives play in the relationship between anxiety and alcohol use.

I had another activity to explain confounding in observational studies (where researchers measure anxiety and alcohol use, without manipulation or intervention). Visitors considered which factors might be associated with both anxiety and alcohol use, and thus the factors researchers would need to statistically account for in their observational research. In my prospective cohort study on associations between adolescent generalised anxiety and later alcohol use, I statistically adjusted for a range of potential confounders, selected based on their associations with both anxiety and alcohol use in the literature. For example, gender, social class, parental depression and anxiety, parental alcohol and tobacco use, adolescent externalising disorders and cannabis and tobacco use.

The Experimental Arms during ‘Unhappy Hour’ |

Finally, I had an activity to highlight one of the challenges of alcohol research; participants are generally poor at estimating the number of alcohol units they consume. Using glasses and pub measures, I asked visitors to estimate how many alcoholic drinks (e.g. beer, wine and spirits) are equivalent to 14 units of alcohol, the government’s recommended weekly alcohol limits for both men and women. Participant errors when recalling units consumed may be due to lack of knowledge about alcohol units, inattention to the size (ml) and strength (ABV) of drinks, memory biases, and social desirability biases.

Anxiety and alcohol use are relatable topics because mental health difficulties are common and millions of people drink alcohol. I hope that after visiting my stall, visitors had a clearer understanding of theories on the relationship, how researchers study the relationship, challenges researchers face, and why this research is important. Despite numerous studies on the topic, the relationship between anxiety and alcohol use remains unclear. Determining the sequence of anxiety and alcohol problems, and the strength and direction of associations between them, is of great public health importance given the personal and societal costs associated with anxiety and alcohol use. If anxiety and coping motives are found to be risk factors for problem drinking, they could become a target for intervention.

Public engagement events are mutually beneficial for both researchers and the public. For researchers, they are an opportunity for us to share our work, understand different perspectives by talking to people outside of our specialty, develop communication skills and be creative. Public engagement events are also a chance for the public to learn more about the latest research that is taking place at universities and how it impacts wider society, and to share their own insights, experiences and suggestions.

Thanks to the Bristol Doctoral College for the opportunity to participate in this fun public engagement event. I encourage all University of Bristol postgraduate students to take part next year!

Written by Maddy Dyer, PhD Student at the University of Bristol Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group in the School of Experimental Psychology.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.