In March 2012, the process of reviewing the UK’s drinking guidelines began. Proposed revisions were published in January 2016 and final guidelines in August 2016. The question is, did they have any effect?

According to The Government’s Alcohol Strategy, the point of reviewing the guidelines was to ‘support individuals to make informed choices about healthier and responsible drinking’ (p. 4). The changes to the guideline were based on a comprehensive review of the epidemiological evidence on alcohol-related health risks. Particular attention was drawn to new evidence on the risk of cancer associated with drinking and increased uncertainty regarding evidence that alcohol is good for your heart. The guideline figure was set at 14 units a week, a level approximately equivalent to a 1% lifetime risk of dying due to alcohol. The advice suggested that this should be spread across three or more days and the new lower risk guideline is equal for men and women since the level of risk from consumption at the guideline level is similar for both sexes.

So, the guideline was developed to provide information about the risks of drinking. It tells the public that if they drink under 14 units per week and spread those units out then their risk from drinking is fairly low (but not zero). This information attracted widespread attention when the change was announced but, since then, has been minimally promoted by the UK Government, although there has been some smaller-scale media activity from other interest groups.

We used a sample of 16,779 drinkers from across England to see if there were any changes in factors which affect whether they are likely to drink in a healthy way (see the paper here). We drew on the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM-B) model which proposes that, in order to change their behaviour, a person needs to be capable of the new behaviour, have the right resources to implement it and want to do so. We might expect that if a new set of guidelines results in increases in capability, opportunity or motivation to drink more healthily (eg if people feel more able to track the units that they drink), a positive change in behaviour might result. It is important to test for changes in these antecedents of behaviour change as, in the absence of such change, it is less likely that the guidelines will have promoted changes in drinking behaviour.

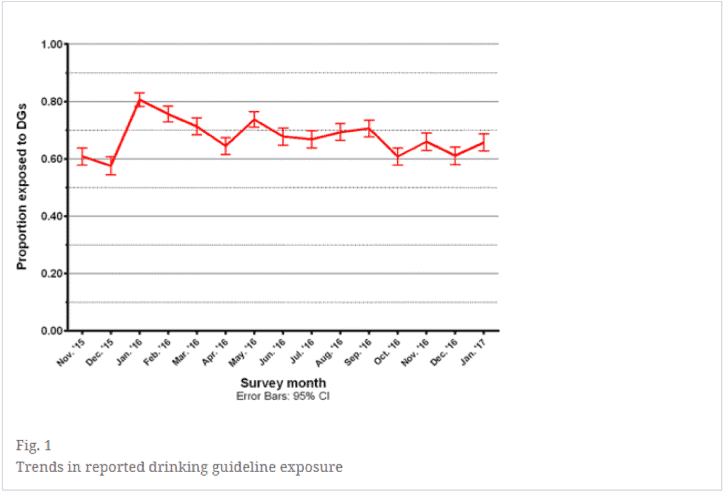

We asked ten questions measuring capability, opportunity and motivation and categorised answers as being likely to contribute (positive) towards healthier drinking or not. The figures below show how many people gave positive responses over time. We also looked at whether people had heard of drinking guidelines and seen the recommended lower risk figure in the last month. As you can see in figure 1, more people (58% in December 2015 and 81% in January 2016) had heard of the guidelines in January 2016. But did their capability, opportunity and motivation to drink in a healthier way also change?

|

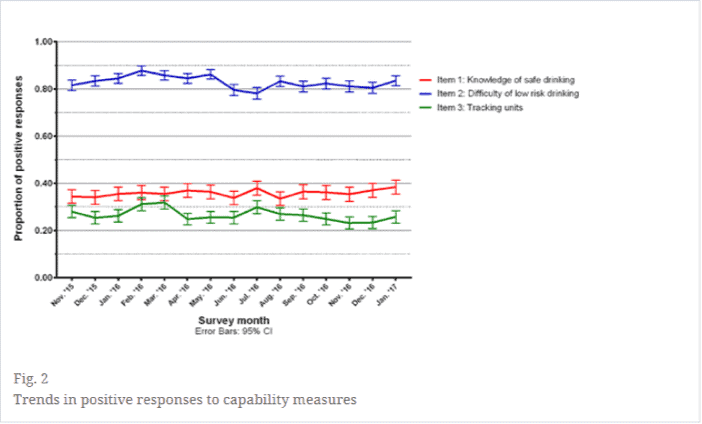

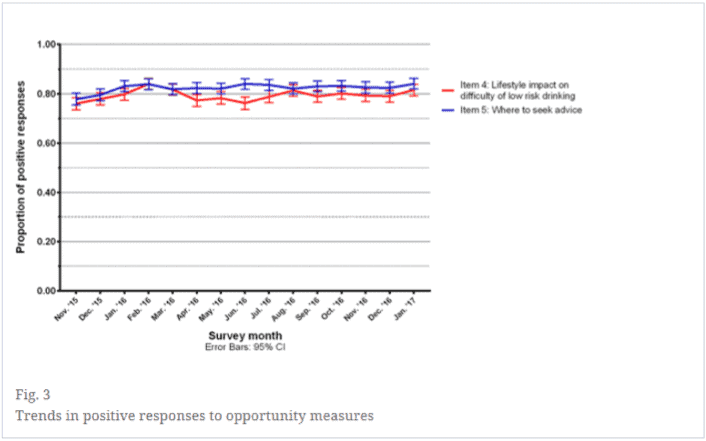

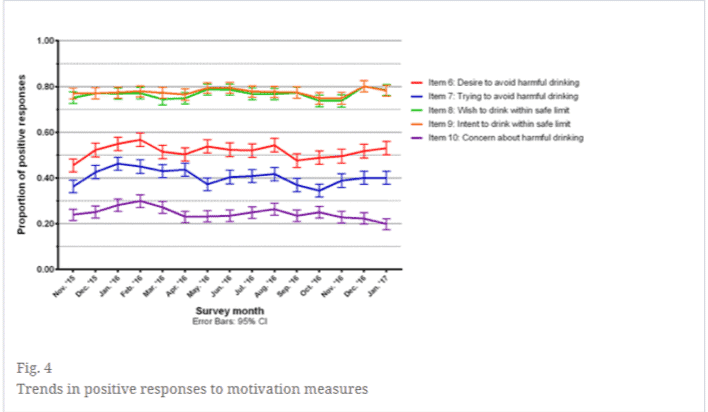

The three graphs below show the proportion of positive responses over time to measures of capability, opportunity and motivation. There wasn’t much change over time, and any small improvements disappeared within a few months. Interestingly, around 80% of people felt that it was easy to drink safely and that they wanted to drink within a safe limit but much lower proportions of people knew what the guideline figure was, tracked their units and were concerned about harmful drinking.

|

|

|

It seems then, that we cannot find any evidence of change in the COM-B determinants of drinking behaviour corresponding to the publication and promotion of the new lower risk drinking guidelines. This could have been due to the lack of sustained promotional activity. For example, guidance on communicating the new guideline on UK alcoholic product labels wasn’t published until March 2017 and there has been no large-scale TV or radio campaign.

Since publishing and promoting the new guidelines does not seem to have influenced the COM-B determinants of behaviour change, it is unlikely that the aim of informing healthy drinking choices was met. In order to achieve this, greater efforts to promote the guidelines may have been needed.

Written by Abigail Stevely, PhD Student at the University of Sheffield.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.