Alcohol can harm individual drinkers; it is a carcinogen in the same classification as tobacco and asbestos, it is the leading cause of liver disease, and it is a psychoactive drug of dependence associated with numerous mental health problems including depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide.

However, harm from alcohol is all too often experienced beyond the individual drinker. Such harms include physical violence, drink drive accidents, relationship problems, domestic abuse and child neglect.

How does alcohol misuse affect children and families?

A report published by the Institute of Alcohol Studies in 2015 found that rates of harm experienced by another person’s drinking were high. 79% of people surveyed in England had experienced second hand harm in the past year. 10% reported marital problems or relationship breakdown and 4.5% reported that a child they were responsible for had been negatively affected by someone’s drinking.

I would encourage people to watch our short animation video summarising the key findings, which is available on the IAS website.

Evidence shows that alcohol problems have a significant and damaging impact on children. To use the buzzphrase of the day, a child’s “life chances” can be severely impeded by alcohol misuse either drinking themselves or by a parent or carer’s drinking.

Children who misuse alcohol are at greater risk of health and social problems compared to adults, because their mental and physical faculties aren’t fully developed. Negative consequences of underage drinking include greater risk of dependency in later life, poor educational attainment, damage to the developing brain, physical violence and risky sexual behaviour.

In terms of how parental alcohol misuse can impact on children, a report by Turning Point in 2011 found that more than half of parents receiving treatment said they were unable to provide children with the support they needed due to their alcohol use with 47% saying their focus was on alcohol not parenting.

Alcohol is estimated to be implicated in up to a third (25-33%) of child abuse cases, and more than 4,000 children each year contact Childline with concerns about their parents’ drinking, which is the most frequent worry children have about their parents when they call.

The final point of evidence I’d like to draw attention to is alcohol’s relationship with poverty and inequality. Evidence from home and abroad shows that people with lower income, education or employment status are much more likely to die or suffer from a disease as a result of their alcohol consumption or experience harms from another person’s drinking.

Given that alcohol harm is often concentrated in our most deprived communities, tackling this problem can be seen as a major step towards reducing inequalities.

With an estimated 28% of UK children currently living in poverty according to the Child Poverty Action Group, tackling one of the major drivers of inequality and deprivation should be a priority for this government and I would hope that action on alcohol harm would be a key pillar of the forthcoming Life Chances Strategy.

Evidence of ‘what works’ to reduce alcohol harm

After framing a rather bleak picture, I would now like to turn to more positive information about how we can improve this situation.

There is strong and consistent evidence of ‘what works’ to reduce alcohol harm and eminent bodies including the OECD, World Health Organisation and NICE have made similar recommendations to the UK government for what to include in an effective alcohol strategy.

All the evidence shows the best outcomes will be achieved through population-level prevention measures.

It is of course also essential to provide access to good quality treatment services for people with alcohol problems. However, there are many heavy drinkers who may not display symptoms of dependency but do significant damage to themselves and others. And it is always better to build a fence at the top of the cliff as opposed to sending ambulances to the bottom.

The most effective policies that reduce harm across society, including the most vulnerable groups, involve government regulations on price, availability and promotion of alcohol.

It will come as no surprise to hear that regulatory measures such as raising prices are not the most politically popular. However, the evidence of their effectiveness is compelling.

Price

For example, high strength white cider can be bought for as little as 16p per unit. These products are predominantly drunk by dependent and underage drinkers. A 3-litre bottle of high strength white cider can contain the same amount of alcohol as 22 shots of vodka, yet they are commonly sold in shops for as little as £3.50. These products attract the lowest rates of alcohol duty, about a third of the duty levied on beer of the same strength.

A minimum unit price would set a floor price for alcohol, which would raise the price of the cheapest products such as white cider.

The University of Sheffield have produced robust data estimating the impact of a minimum unit price. If set at 50p, at full effect it would result in almost 1,000 fewer deaths, 30,000 fewer hospital admissions and 50,000 fewer crimes each year. Perhaps most compelling is that 80% of lives saved would be people from the lowest income group, meaning this policy could be a major step forward in tackling health inequalities.

Availability

Turning to the availability of alcohol, studies show that areas of deprivation have higher numbers of licensed premises, mainly off-licenses, compared to better off neighbourhoods. This exposes poorer communities to an environment that fosters unhealthy behaviours and is linked to higher rates of harmful drinking.

There are two important steps this government could take to tackle the problems associated with excessive availability of alcohol, and the impact this may have on children and inequalities.

Firstly, the licensing laws could be amended to ensure that consideration is given to the health and wellbeing of the local community when an application for a new alcohol license is made. Scotland currently has what is known as a fifth objective in its licensing laws, which ensures that health is taken into consideration.

Secondly, more engagement from child protection services in the alcohol licensing process could be supported. Currently, one of the 4 key licensing objectives is ‘the protection of children from harm’. However, child protection services are not statutory consultees when licensing authorities set their policy and their engagement in the whole process is uncommon.

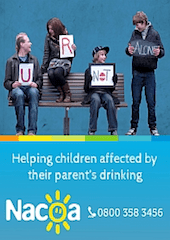

Lord Brooke of Alverthorpe, a great supporter of reducing alcohol problems, has very recently tabled amendments to the Police and Crime Bill to address these legislative gaps in the licensing system. If anyone here (NACOA) is able to support these amendments it would be greatly appreciated.

Conclusion

Each year in England there are approximately 22,000 deaths and more than one million hospital admissions related to alcohol. These are shocking figures on their own, but if we consider that each individual seriously affected by alcohol has a family, many are parents and grandparents, it’s clear the effects of alcohol are felt by a much wider population.

Often less attention is awarded to the harm that alcohol causes to people other than the drinker, including children. On balance, current policies relating to alcohol perhaps place too much emphasis on individual responsibility and do not take sufficient consideration of alcohol’s harm to others.

Problems with alcohol are not limited to a small minority of irresponsible drinkers, they are wide ranging and can be seen as everybody’s business. As taxpayers we all contribute to the costs borne by the NHS, emergency services and criminal justice system, and as a society we have a duty to protect and support our most vulnerable communities, including children.

I welcome this important campaign which shines a light on an often neglected issue. I hope it spurs meaningful, evidence based policy action on alcohol harm.

This post is an abridged version of IAS Director Katherine Brown’s address to the inaugural APPG for Children of Alcoholics, hosted by The National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) on 15 September 2016.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.