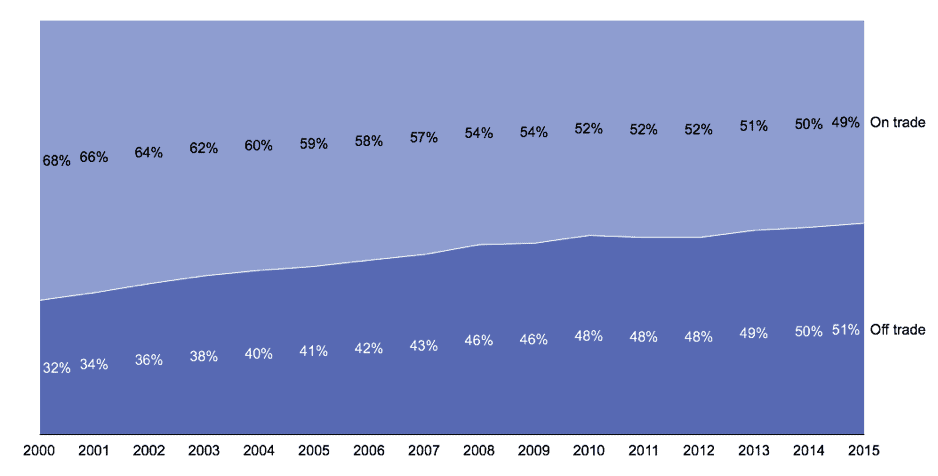

In 2015, for the first time, British people drank more beer at home than they did in the on-trade (pubs, clubs, bars, hotels and restaurants), according to the British Beer and Pub Association (BBPA). This ongoing shift away from drinking in pubs continues to cause concern: quite apart from the perceived social and cultural benefits of pubs, there are various health and safety concerns associated with the growing dominance of cheap supermarket and off-license products. Drinking in the on-trade is overseen by staff who have a duty of care to their patrons, and who can regulate the measures they serve. By contrast, drinking in the home is less monitored and subject to fewer constraints. ‘ Pre-loading’ , where people drink at home before going out to pubs, clubs and bars is seen as particularly problematic, associated with higher levels of consumption, violence and sexual assault.

Share of Beer Sales Volume, On-Trade vs Off-Trade

Source: BBPA Statistical Handbook 2016

In response, the BBPA “called on the chancellor, Philip Hammond, to repeat George Osborne’ s surprise cut to beer duty three years ago to boost the pub trade”. There is no evidence to suggest this would work. In fact, there is reason to suspect it would backfire, and accelerate the shift towards supermarkets.

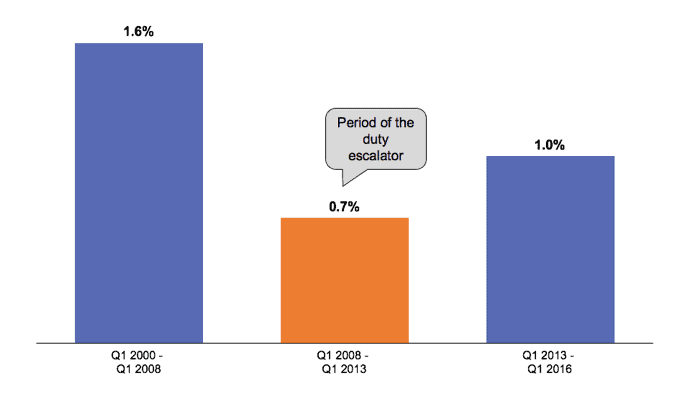

The alcohol duty escalator, which raised beer taxes by 2% above the rate of inflation each year, appears to have slowed the relative decline of the pub trade. Between its introduction in the first quarter of 2008 and its scrapping in the first quarter of 2013, the on-trade’ s share of beer sales declined by 0.7% a year. By comparison, in the eight years prior to the duty escalator, the on-trade’ s share had fallen by 1.6% a year. Since 2013, it has risen again to 1.0%.

Annual Percentage Point Decline in On-Trade Share of Beer Volume Sales

Source: BBPA Quarterly Beer Barometer

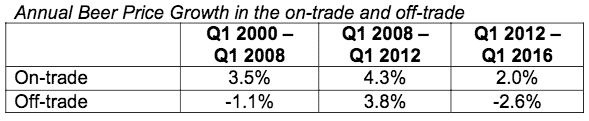

People choose to buy alcohol from supermarkets rather than pubs because it is cheaper. To a significant extent, the shift towards the off-trade is the result of this price differential widening. Yet in the lifetime of the duty escalator, the premium on beer in the on-trade grew at a slower rate than either before or after.

In the duty escalator period, higher beer taxes ensured that prices in the off-trade rose almost as quickly as prices in the on-trade: 3.8% per year, compared to 4.3%. In the time either side of the duty escalator, prices fell in the off-trade, but continued to rise in the on-trade.

Annual Beer Price Growth in the on-trade and off-trade

Source: ONS RPI Time Series

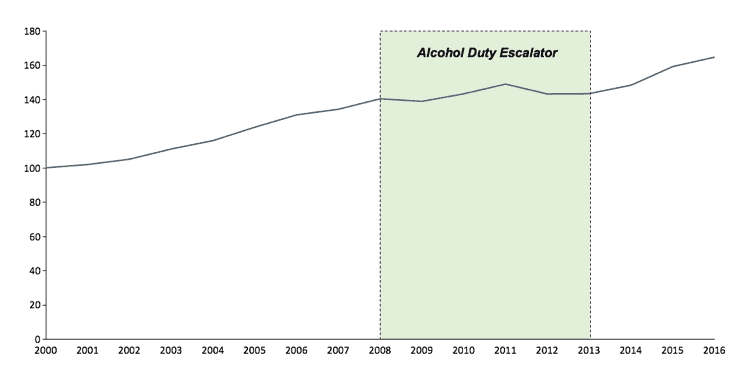

The chart below shows the effect of these changes on the price differential between the on and off-trade, which grew rapidly between 2000 and 2008, slowed while the duty escalator was in force, and has been rising again since 2013.

Ratio of On-trade and Off-trade Beer Duty Retail Price Indices (Indexed, Q1 2000=100)

Source: ONS RPI Time Series

Sceptics may attempt to shrug this off as correlation, not causation. After all, the period 2008 to 2013 was marked by turbulent economic conditions, which may also have affected beer prices and consumption. Yet many pub owners themselves have expressed scepticism about the effectiveness of duty cuts in supporting the on-trade. Earlier this year, operators responsible for over 100 pubs wrote an open letter to the Government, claiming that they had seen little benefit from previous duty cuts, which had not been passed on by brewers. By contrast, supermarkets have much stronger bargaining power, and so can negotiate a greater share of duty cuts from brewers than pubs. The publicans themselves, therefore believe that cutting duty “exacerbates the on-trade/off-trade price differential with consequent social and health impacts”.

There is an alternative, albeit counter-intuitive, way to reverse the shift away from pubs towards the supermarket. Minimum unit pricing (MUP) has been described as “exquisitely targeted” towards the most harmful drinkers. It is similarly well focused on the off-trade. An MUP of 50p would make it illegal to sell alcohol for less than 50p per unit (equivalent to £1.14 for a pint of 4% beer). Less than 1% of beer is sold so cheaply in the on-trade, but over half of off-trade prices are below this level. An MUP would therefore raise prices in supermarkets but not pubs, and narrow the price differential between them. The health benefits of MUP are well rehearsed, but it could also be the first step towards reversing the long march away from pubs.

Written by Aveek Bhattacharya, Policy Analyst at the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.