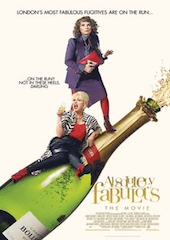

With Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie arriving in cinemas this weekend, it is an apt moment to consider whether we are in fact living in ‘Ab Fab Britain’, as the journalist Fraser Nelson has suggested. According to Nelson, the sitcom, which tells the story of a ‘hedonistic’ hard-partying, heavy-drinking, drug-taking mother (Eddy) and her straight-laced daughter Saffy “was never intended as a piece of social commentary — yet it has turned out to be bizarrely prophetic”.

Young people today are much less likely to drink than previous generations. The proportion of English 11-15 year olds to have tried alcohol has fallen from 61% in 2003 to 38% in 2014. The Ab Fab theory suggests that this is a conscious rejection of the decadent lifestyles of their parents. For example, 18 year old Liam Brooks is teetotal, convinced by the experience of putting his parents’ inebriated friends that “there is no pretty drunk”.

Yet there is no evidence for such a generational backlash. As one systematic review points out, there is a “fairly large and consistent literature demonstrating that more parental drinking is associated with more drinking in offspring”. In other words, a child is more likely to emulate their parents’ drinking than recoil against it.

In fact, the Ab Fab theory is somewhat backwards in that one of the most plausible explanations for falling underage drinking is that parents are more responsible than they used to be, and increasingly less like Eddy. They set a better example: the proportion of 25-44 year olds that drank in the last week has fallen from 68% in 2005 to 56% in 2014. They are less likely to approve of underage drinking: in 2014, 56% of 11-15 year olds believed their parents wouldn’t like them drinking, compared to 45% in 2008. They are more aware of their children’s’ whereabouts: in 2014, only 14% of children had been out after 9pm without their parents knowing where they are, compared to 72% in 2006. They have warmer and more supportive relationships: the proportion of children that ‘hardly ever’ quarrel with their father rose from 47% in 2001 to 57% in 2014.

However, it is not just about parenting. The fact the alcohol became much less affordable in the wake of the recession is likely to have played a substantial role in discouraging young people from drinking. A large body of evidence shows that when alcohol becomes expensive, consumption falls. Alongside the squeeze on wages, and reduced economic confidence, taxes on alcohol rose consistently between 2008 and 2012. For illustration, wine and spirits were 31% more expensive in 2015 than 2007, while the minimum wage for under 18s had risen by just 14%.

This makes the Government’s cuts to alcohol duty in recent years particularly concerning. Adjusting for inflation, since 2012 beer duty has fallen by 14% and cider and spirits duty by 6%. Alongside economic recovery, lower taxes mean that alcohol will become more affordable. This, in turn, puts the progress made against underage drinking in jeopardy.

It is important to note that these two theories – better parenting and reduced affordability – are merely the most plausible based on the limited evidence that we currently have. There is a clear need for further analysis and research, and other claims, such as the notion that improvements in children’s welfare and educational performance have reduced drinking merit further exploration. There is also scope to better understand the link between underage drinking and internet and social media use. It is possible that such activities provide alternative sources of leisure and sociability, but there is little robust data to support this claim. Indeed, some studies suggest the opposite: that children who spend more time online are more likely to drink.

While few hypotheses are conclusively disproved by the existing evidence, a couple of proposed explanatory factors can only have made a modest contribution to falling underage drinking. For example, substantial attention has been focused on stricter enforcement of ID policies, making it harder for under 18s to buy alcohol. Yet at peak, fewer than 6% of children tried to buy alcohol from a shop, and fewer than 5% from a pub. Parents and friends are a much more significant source of alcohol, and have declined by more (in absolute terms) than self-purchasing as a source of alcohol.

Another commonly held theory is that demographic change resulting from immigration is the main cause of falling underage drinking. Again, while these changes have had some effect, they are unlikely to be especially large. Ethnic minorities are less likely to drink, and have grown as a proportion of the population. However, drinking has fallen across children of all backgrounds and in fact, the decline has been greatest among white children.

While there remains much to understand about the decline in underage drinking, it is critical to ensure that these positive trends are sustained. Doing so is likely to involve further research to explore the phenomenon in greater depth, and tax policy that resists the market’s tendency towards ever cheaper alcohol.

Written by Aveek Bhattacharya, Policy Analyst for the Institute of Alcohol Studies.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies.