It was supposed to be the first study in Canada to test alcohol warning labels.

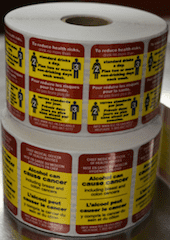

Yukon, a remote territory in northern Canada, would affix bright yellow labels to all its alcohol containers for eight months. The labels, designed using feedback from focus groups conducted in Yukon with local stakeholders, including Yukon’s Chief Medical Officer of Health and the general public, contained messages about alcohol’s link to cancer (particularly that of the colon and breast) and information on Canada’s low-risk drinking guidelines. Further down the road, labels telling consumers how many standard drinks were in each alcohol container would be rotated in. After the labels had been in circulation for a few months, researchers would survey consumers to see if the labels had raised awareness about alcohol-related cancer, low-risk drinking guidelines and standard drinks (national data indicate fewer than 3 in 10 Canadians know of the causal link between alcohol and cancer, and understanding of the guidelines is low), or led to a change in drinking patterns.

Funded by Health Canada and co-led by Public Health Ontario scientist Erin Hobin (PI) and Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research director Tim Stockwell (Co-PI), the Northern Territories Alcohol Study was an opportunity to test the effectiveness of alcohol labels in the real world. Yukon’s high level of alcohol consumption—the highest per capita consumption in Canada—and elevated cancer rates made it a great candidate for the experiment. In a news release from the University of Victoria, Stockwell commended the Yukon government for being the first jurisdiction in Canada to provide detailed labels on alcohol containers.

But it was not to be. On the Friday before Christmas—just one month after the first labels hit store shelves—the Yukon government announced it was putting the project on hold due to complaints from the alcohol industry. A news article ran in the local Whitehorse Daily Star newspaper, and then things were quiet as everyone went about their holidays. But unfortunately for the alcohol lobby, this story was not to be forgotten about after the gifts were opened and the last of the leftover turkey was consumed.

On January 2, prominent health columnist André Picard of the Globe and Mail published a scathing piece, calling the removal of the labels “shameful.” The same day, CISUR’s Stockwell was interviewed on As it Happens, a national current affairs radio show on CBC, Canada’s public broadcaster. (PHO’s Hobin had been interviewed for the program when the study first launched). Coverage from the National Post, Canadian Press wire service and even the New York Times followed.

Previously unnamed industry representatives were forced to come forward and explain their opposition to the labels in the media. Spirits Canada president Jan Westcott said they were “just not sure that putting the word ‘cancer’ on a label” was the most effective way to tell people about alcohol’s well-documented cancer risks. Luke Harford of Beer Canada told the Whitehorse Daily Star and the New York Times that he was concerned people might mistake labels outlining low-risk drinking guidelines for acceptable limits for drinking and driving, despite decades of awareness campaigns about the risks of combining driving and alcohol and rates of impaired driving are plummeting.

The Times piece also quoted Westcott and Harford as saying they had never suggested they would take legal action in response to the labels, but the Yukon government obviously felt differently. As John Streicker, the Yukon cabinet minister responsible for the Yukon Liquor Corporation, told the Times: “We need to do the responsible thing, which is to judge whether that’s the best use of our money for our citizens. The hard choice is whether to pay for lawyers or whether to pay for harm reduction.”

One has to wonder what the industry players hoped to achieve by interfering with the study. Yukon is a small, remote jurisdiction. If the study had continued, a portion of the territory’s 36,000 people would have seen the labels over the eight months they were in place. Now, close-up photos of the bright yellow stickers have accompanied most of the media reports around the stoppage of the study, which have far outnumbered the stories published about the project when it was first rolled out. If the goal was to set an example and intimidate others into not adopting labels, it’s unclear if that has been effective; other jurisdictions and groups considering warning labelling on alcohol containers have said they are undaunted by the industry pushback seen in Yukon.

What does this all mean for the future of the Northern Territories Alcohol Study? Negotiations are ongoing and researchers are hopeful that the study will continue, with Stockwell suggesting in his As it Happens interview that perhaps a third party could step in to support the Yukon government. But industry interference means the design of the study—a rare opportunity to learn from a natural policy experiment what this kind of labelling can do to awareness, knowledge and behaviour—has already been compromised, even if it does resume.

Whether or not the project goes forward, one thing is clear: thanks to extensive, high-profile media coverage, far more people have seen the warning labels than researchers could have hoped for, which may be an intervention in itself.

Written by Amanda Farrell-Low, communications officer at the University of Victoria’s Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.

All IAS Blogposts are published with the permission of the author. The views expressed are solely the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Alcohol Studies